Australian rivers are in crisis, with reduced flows from massive irrigation pumping and extinction of native species accelerating at a frightening pace. The crisis is particularly severe on the many reaches of the Darling and Murray Rivers, which drain the east and north of the continent, joining and emptying into the sea on the southern coast. This is Australia’s longest and most productive freshwater system and its importance cannot be overstated. Conservationists have been outspoken in their demands that these rivers be restored to health through a range of measures including major reductions in the extractions allowed for agricultural irrigation. This call has been encapsulated in the phrase ‘environmental flows’ which signals the ecologists’ demand that restoration of flows and overall health of the rivers is essential for their biodiversity—and indeed for our survival.

This debate over river health has also been where aboriginal voices have been heard most strongly. Aboriginal people have been demanding not only ‘environmental’ but ‘cultural flows’, which they argue must be recognised as essential to this threatened river system. The Murray and Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations collective (MILDRIN), for example, on the rivers’ lower reaches, has called for the recognition of cultural flows in the national context of both the Native Title cases on river rights, (which partially recognised aboriginal people’s pre-invasion property rights in the common law) and the legalisation of tradable private property in water. This call for the recognition of an aboriginal interest in the river is not new. It draws on the centrality of water to traditional philosophies and social life as well as economies, but it also reflects responses and interactions to the changes caused by two centuries of settler land management.

It might be expected that ecologists and aboriginal defenders of rivers would be in complete agreement. After all, the need to recognise ‘Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ or TEK is now a standard requirement of all, natural resource management guidelines. Yet relations between ecologists and aboriginal people in Australia have often been less than smooth—in fact, they have often been in open conflict. This paper will consider a local case study on the upper Darling system: the Brewarrina Native Fisheries, known in local aboriginal languages as Ngunnhu and in colloquial aboriginal English as ‘The Rocks’ or ‘The Fisheries’.

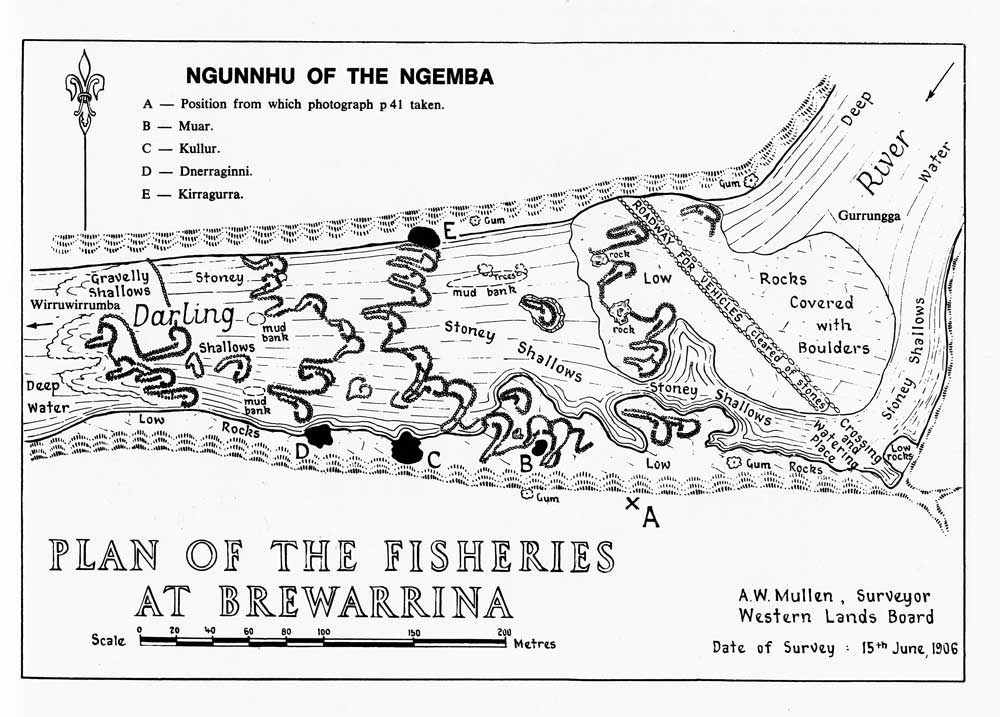

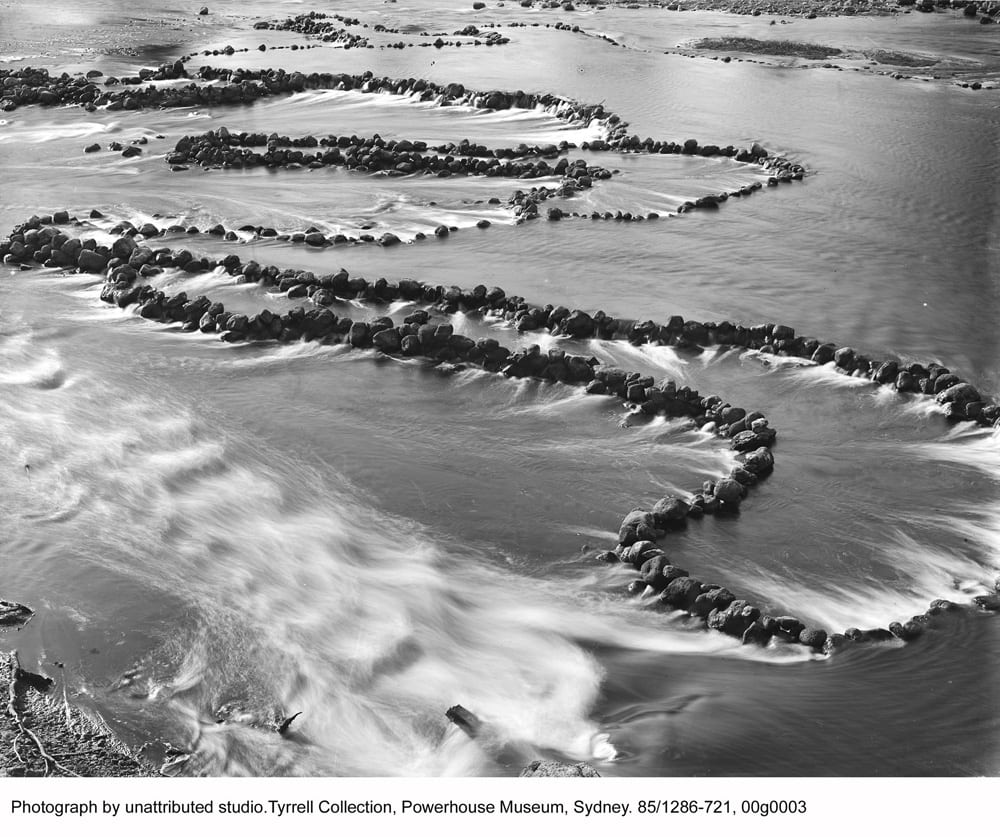

This site, like all river stretches of the Darling, has rich aboriginal traditions of embedded stories told about, and through, the landforms and flows of the river. Ngunnhu is unusual, however, because of the fish traps. The Brewarrina fish traps were a complex network of rounded pens, extending 500 metres around the bend of the Barwon River where Brewarrina now stands. There are many other stone fish traps in the long Darling River system but none are so long or so well-placed as Ngunnhu. These Brewarrina traps are an extraordinary feat of engineering, reflecting deep knowledge of the river’s behaviour in drought and flood as well as showing painstaking, stone-on-stone construction methods. The stone pens were laid out in a matrix along the length of the river in which the bed falls steeply at the same time as it bends. This ensured that no matter how low or high, fast or slow, the river was running, at least some of the pens would be underwater and so able to entice the fish in and then trap them, leaving them swimming safely but unable to find the small downstream opening through which they had entered. The high productivity of the traps meant they could feed many people, so they were the subject of elaborate protocols ensuring neighbouring peoples had rights to the river in times of drought. The traps were the focal point of large ceremonial gatherings, which brought together not only people from the three language groups adjacent to the river but often people from a country that was far more distant from the river. No matter how long the ceremonies took, the traps ensured that many hundreds of people could be fed well for weeks at a time.

One of the major sustained concerns of the aboriginal people has been about the physical damage to the structures and living ecologies of the rivers. The remaining section of this paper will focus on the pressures which were brought to bear by the aboriginal people on aquatic ecologists when they tried to build a new fishway across the weir.

Brewarrina aboriginal communities have continuously stressed their concerns about damage to the river. This is a concern arising partly from settler disregard for the sacred story and partly from concerns about the settler’s weir – built in the early 20th Century to store water for the town in an area of unpredictable rainfall. The weir site was chosen to enhance an already deep part in the river, but its effect was both to obscure the deep area and to submerge more stone traps of the Ngunnhu itself. Furthermore, its concrete wall completely obstructed the natural movement of fish upstream to spawn. Each season after the weir was built, native fish would be found in massive numbers trapped below the weir, floundering and gasping as they crowded and died in attempts to move upstream. To address this glaring problem, government authorities had built a ‘fishway’ or ‘fish ramp’, a geometric set of rising concrete steps which protruded downstream from the wall on the northern, shallow, side of the river. Fish had never used this path to swim upstream—they had always chosen the southern—deeper—side of the river. So the fishway was poorly positioned, but in any case, its construction blasted even more of Ngunnhu’s pens apart, causing more physical and symbolic damage. Aboriginal fears were heightened even further after the expansive 1974 flood which had allowed European carp (Cyprinus carpio), initially introduced in southern ponds of the river as an ornamental fish, to escape into the main river system. The species spread rapidly all the way up the length of the system, at least into its major streams. The carp, although widely eaten throughout Asia, are viewed with disgust by Aborigines and settlers alike, deemed inedible because of their taste, their distinctive odour and their many fine bones.

The general aboriginal distress about the impact of the weir has been continuous. Aboriginal people mounted a campaign for a greater say in the management of the river as a heritage resource. Les Darcy, a Ngiyampa man who grew up on the river, was an early director of the Cultural and History centre located at the Fisheries. He led the campaign for the Centre to have a role in managing the fabric of the Fisheries themselves, both as a heritage structure and as a productive resource. In this 1996 interview, he reflected on his concerns about the river at Brewarrina, demonstrating that, for him, the weir was just one aspect of the severe impact which European settlement and western irrigated agriculture had made on the river:

…It’s a shame we can’t live the same way . But there’s no more reeds, there’s trees all over the river falling in. The European carp have got it beat. I don’t think the irrigation has helped one little bit. Neither have the weirs… I often comment about building the weir at Brewarrina Rocks. They put a weir where it’s been 60 miles of water running in any man’s time. It’d never been known to get dry, it’s the deepest part of the Darling River, so why put a weir where the deepest part of the Darling River is? Why put a weir at all? It’s a terrible way of ruining a river.

Les was scathing about the building of that first fish ramp which was not only ‘on the wrong side’ of the river but then…

…they had to dynamite rocks for at least 50 yards to make a waterway for the fish to come up, and the fish want their natural course. … It shows you the thought and intelligence that went into the building of the weir at Brewarrina.

Now, Les said, the failure of the first fish ramp meant ‘they’re thinking they’ve got to put it on the other side.’ But for him, the weir and the first fish ramp had already demonstrated that ‘expert’ government authorities did not understand the ecology of the river and therefore should not be trusted with any more decisions at all.

The grim concrete channel leading up to the weir on the far side of the river was ugly, but that was the least of its problems: as Les had pointed out, its failure to allow fish to swim upstream was sadly visible. Concerns about both weir and fishway gained even more momentum when, after big floods in 1974 and 1976, a long drought began, which continued from 1997 until at least 2009. This has made the dominance of carp in the river a common grievance among fishermen, graziers and irrigators, who were otherwise seldom on the same side of any argument.

Aboriginal demands for restoration of fishing resources and a reversal of the damage done by the weir have struck a responsive chord in the New South Wales (NSW) Department of Primary Industry (DPI) which manages freshwater rivers. At Brewarrina, there has been an intense debate about whether and how a new fish way might be constructed. The government has finally recognized the damage done by weirs, as DPI spokesman David Cordina explained:

Native fish need to migrate short and large distances upstream to spawn, find food sources and redistribute. Barriers to fish passage, such as the Brewarrina weir, prevent this migration and as such, weirs are listed as one of the main factors that have contributed to the decline in native fish numbers in the Murray-Darling Basin. Native fish numbers are now estimated to be at just 10% of the pre-European settlement.

The most contentious discussions have been had around the impact that a new fish-way might have on Ngunnhu, the Fisheries. DPI announced in October 2009 that a final agreement had been reached after what its spokesperson, ecologist David Cordina, said was extensive consultation, to build a ‘reverse rock-ramp fishway’ which would be on the southern side of the river and would lie entirely within the existing pool of the weir, that is upstream of the remaining, exposed pens. Cordina continued:

This represents a big win for the native fish of the Barwon River and the integrity of the Ngunnhu, or aboriginal Fishtraps, adjacent to the weir. The Ngunnhu, located immediately downstream of the weir is regarded as one of the most important cultural heritage sites in NSW, and as such every effort was taken to ensure the proposed fishway would only enhance their value.

Yet aboriginal concerns persisted. In letters sent to the Federal and the NSW Ministers for the Environment early in 2010, members of long-standing families in the Brewarrina aboriginal community expressed reservations about the agreement. They did so in terms that aligned with concerns of the past, but in ways that also reflected emerging technologies and new practical expressions for these old problems.

Firstly, these letters broached the question of effective recognition of aboriginal people as owners. They expressed frustration at the claim by DPI to have consulted widely, when the Government department had made extensive use of computer generated digital media tools like GPS mapping and animated projections in the consultative process. The view of the letter writers was that this had, in effect, removed the real decision-making power from an aboriginal community which remained educationally and technologically disadvantaged. This consultation, they wrote, had not used a form of communication which would have allowed meaningful participation in decision making by the broadest number of the local community.

Secondly, the letters expressed concern that the sacred nature of the Fisheries and its precinct had not been adequately recognised in the Government plan, which focused on the fish traps themselves rather than the wider area around the Fisheries. The letter writers argued that, apart from the general disturbance of construction, the government proposal would require the importation of many tonnes of rock from other locations, introducing an alien substance into a sacred landscape, which would again undermine the integrity of the site.

Finally, the letters expressed deep skepticism that NSW DPI could in fact prevent its new fishway from contributing yet more damage to the Fisheries, to the river banks and to the fish themselves. The letters stressed the many damaging outcomes which have already resulted from the settlers’ long interference with the stones of the fishtrap pens for a causeway, in the building of the weir itself and the original fishway – yet none of these damaging impacts had been predicted at the time by the engineers who built them. Why should aboriginal people believe now, the letters asked, just because of a sheaf of computer projections, that the engineers were in any better position to predict the outcome of what appeared to be yet another major intervention in the river’s flow? The letter writers held grave concerns, based soundly, it would seem, on past evidence, that interventions in the river would do more harm than good.

Ngunnhu is, in many ways, an exceptional site: a waterscape of high productivity and complex human design and engineering, demanding recognition of aboriginal people’s knowledge of and successful harvesting of natural resources. Yet, at the same time as it demonstrates human ingenuity, it is embedded within a creation narrative of ancestral power over water, land and living species. The varying flows across its rocks are productive both in food species—for humans and birds—and in the complex stories of creation and continuing interaction between people and the more-than-human world. Aboriginal expressions of concern about Ngunnhu—the place, the river and its flow—show this interaction of both pre-invasion ‘tradition’ and post-invasion historical change. This interaction is typical of disputes about river health along with this long river system, feeding into the sensitivity with which aboriginal people respond to conservation initiatives.

The new Fishway at Brewarrina has at last been completed. It is on the southern side—the Brewarrina side—of the river, and it looks extremely beautiful. Rather than the brutalist concrete geometries of the old fishway, the new one is a rising arrangement of stones, echoing the design of Ngunnhu itself. But does it do the job everyone wants it to do? Does it allow native fish to swim upriver to spawn? Fish can no longer be seen gasping as they crowd together in frustration below the weir in the way they used to. The ecologists are cautiously optimistic, monitoring the fishway carefully, waiting to see if there are signs of regeneration among native species. Aboriginal community members have mixed views—many remain skeptical, reserving their judgement to see how the fishway works in drought as well as in rainy seasons. The long undertaking of the planning and then New fishway on the southern side of the river, rising in steps to the level of the weir pond. NSW Public Works Department: https://www.publicworks.nsw.gov.au/riverina-western/Brewarrina-fishway the construction of this fishway is a testament to the changes which have taken place—not only in the river but in the relations between aboriginal owners and settlers. Ecologists have had to recognise aboriginal people as owners of the river in ways that have never occurred before. The beneficiaries in this still fragile negotiation, it is to be hoped, will also be the riverine species who may finally find their way upstream.

Further reading:

Jessica Weir and Steven Ross. 2007. ‘Beyond native title: the Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations’. In The Social Effects of Native Title, (Eds B Smith and F Morphy), ANU Press, Australia.

Donna Craig. 2005. ‘Indigenous Property Rights to Water: environmental flows, cultural values and tradeable property rights’, CSIRO paper.

Paul Sinclair. 2001. The Murray: a river and its people, University of Melbourne Press, Australia.

Heather Goodall. 2011. ‘Reclaiming Cultural Flows: Aboriginal People, Settlers and the Darling River’. In Outside Country: A History of Inland Australia, (Ed Alan Mayne) Wakefield Press, Adelaide, pp 95-126.

Heather Goodall. 2008. ‘Riding the Tide: Indigenous knowledge, history and water in a changing Australia’. Environment and History. 14: 355-84. doi: 10.3197/096734008X333563

Photographs: www.environment.gov.au, Peter Dargin, www.publicworks.nsw.gov.au