It is impossible to know where to begin in situations like these; it feels as if I almost knew Ravi Sankaran all my life. It must have been after the mid80s that we met. An incident comes to mind immediately. There was a seminar at Topslip, in the Indira Gandhi National Park. It wasn’t very inspiring. People were waiting for the clock to strike 5; a ride around the park had been promised. I hunted down Ravi to check whether he was coming. “Of course not! I do this for a living, why should I do it when I’m on vacation”? Now, why haven’t the rest of us realised this?

Ravi started work with the Lesser Florican – a bird of open grasslands. This continued almost to the present, with Ravi having to grow a large moustache before going to Rajasthan and Gujarat every year. This research led to major initiatives in conserving this heavily hunted species, involving active partnerships with villagers and Forest Departments. Ravi always insisted on spending a lot of time with local residents explaining sustainable use to them, and this was the first such effort, and possibly the first-time village communities had been made active partners in a bird conservation programme. This was followed by a major study on the Nicobar Megapode and then the edible-nest swiftlet, which is still ongoing. We used to say that he started with the ‘birds people ate’, went on to the ‘birds whose eggs people ate’, people ate’! Then he was involved in an ornithological survey of the Nanda Devi National Park. He did a short stint on the Narcondam Hornbill, where his major recommendation was that goats on the island be eradicated, and which was immediately acted upon by the Department of Environment and Forests of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Due to the rapport, he had developed with the Forest Department, the traditional suspicion of researchers had disappeared by the time the rest of us began working in the Andamans, and it is difficult to think of another area where researchers and the Forest Department work in such close collaboration. Finally, there was the Nagaland initiative, which I am unfortunately not familiar with.

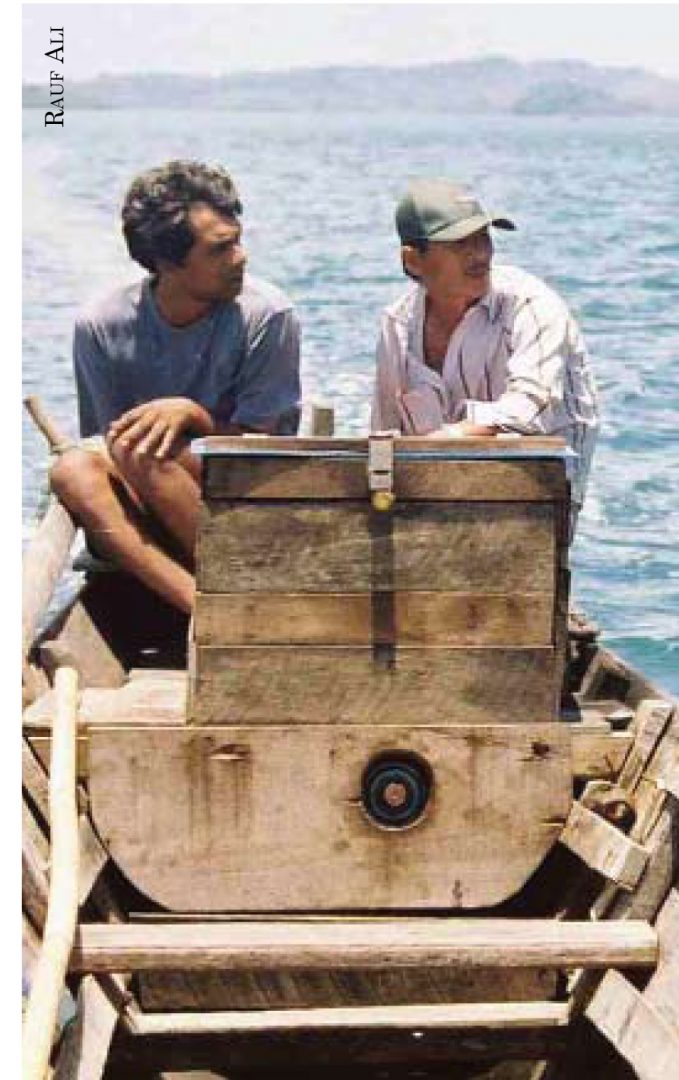

Our Andaman association started formally in December 2000, when we met in Mayabunder. Ravi and I often remembered the New Year’s Eve in 2000 which consisted of eight men going on a boat to Aves Island with an equal number of whisky bottles. This was followed by some fairly intense snorkelling at dawn. On return to the Karen village where we were staying, the mood there seemed much lighter. The Karens had believed that the world was supposed to have ended the previous night and was rather agitated at their padre that this had not happened.

The swiftlet project, easily the best ‘conservation for development’ project of its kind in the country until it fell afoul of well-meaning but ignorant environmentalists, had just started. The logistics of it, however, were a nightmare. If the cave was unattended even for 15 minutes over a weeks’ period, people would rush in, grab nests and run out. The value of each nest made it lucrative for people to watch the guards (in hiding) for long periods of time, just waiting for the break in concentration from the protection squad. It was obvious that the only way it could work was if the people looking after the caves had a long-term economic stake in the birds.

Unfortunately, there was a second school of thought. Put the species on the protected list and all will be taken care of. However, in this case, the nests are being harvested, akin to honey being taken from a hive (in this case, rejected honey would be a more appropriate analogy). As soon as the species is put on the protected list, its products also become protected. End of the conservation program, and it is shocking that even eight years later the Ministry of Environment and Forests is loath to reverse its decision. Meanwhile, the status quo has somehow been maintained, largely because of Ravi’s refusal to give up, and the interest and funding provided by the Forest Department.

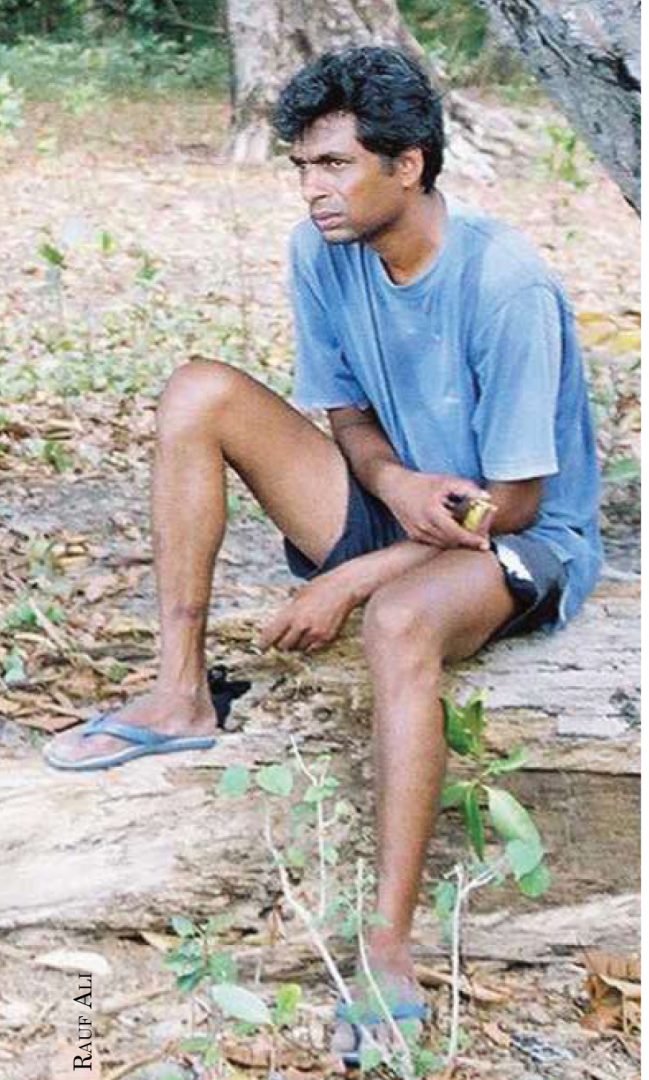

The first camp for Ravi’s swiftlet project was on Interview Island. As luck would have it, Dr Alok Saxena, the Chief Wildlife Warden, had asked me to do a status report on the elephants of Interview Island. We found that this ‘uninhabited’ island had a population of about 10 primary school dropouts and 2 Ph.D.s in 2001. For the elephant study, we had built an elaborate network of machans all over Interview Island. Unfortunately, the elephants would only come there at night, and we didn’t have the equipment to photograph them. Like all good plans, this was tossed out of the window, and we took the help of Karen trackers who learned to identify individual elephants during the survey.

Ravi was a regular visitor at ANET, where I was based for the next few years. His visits were always a mix of very intense science and very intense alcohol consumption. J.C. Daniel, in one of his monthly newsletters as the Secretary of the BNHS, called us the “two mavericks of Indian wildlife biology”, or some such thing. We argued one evening about who was getting complimented and who insulted.

We worked together after the 2004 tsunami when he came to spend a few weeks in Pondicherry to prepare the maps for his tsunami report. We decided that we had to do a project together there. We came up with a project on the preparation of and marketing virgin coconut oil, that was traditionally used by the Nicobaris. In May 2007, we spent a week in the Nicobars working on a prototype. It took another year to get funding, and then I had problems getting a tribal pass. The reason for this is still not clear. On January 15 this year I called Ravi to tell him that I was returning the funds to the Department of Science and Technology since I didn’t see the tribal pass happening. He told me to fight it out. I am now sitting at the ANET dining table in Wandoor, where we have spent many great, and many totally forgettable evenings together, waiting for my flight to the Nicobars tomorrow.

My organisation, FERAL, had organised a seminar on coastal management after the tsunami, in August last year. By this time, Ravi had been induced to come onto our Research Advisory Board, and we had decided that he would handle the tough job of chairing the final discussion. How do you run a seminar where half of them are from the Forest Department and the other half researchers, and still stop the fur flying? As it turned out it was one of the best seminars I have ever attended, with a lot of serious science being spoken and taken note of.

How does one end the eulogy of a friend – one of the most challenging, exasperating, fun, provocative and plainly stark raving mad persons I’ve had the privilege to know? Rewind to the one-minute silence in his homage at the BNHS 125th anniversary conference in Bangalore a few weeks ago. The projection booth operator, on seeing everyone stand up, hit the button for the national anthem. Through most of that minute, we were treated to the antics of the organisers trying to get him to switch it off. Ravi was laughing the hardest, I’m sure.