After an early morning rush to the airport, I wake from my sleep, soothed by the smooth Malaysian highways, and look with bleary eyes out of the window. I have to blink a few times to make sure I’m not still dreaming. We left Kuala Lumpur only a few hours earlier, and when I drifted off the road was lined by the plastic blooms of palm oil plantations, robotic rows stretching to the horizon. But the vegetation on either side is now too chaotic, too green, too beautiful, to be anything other than proper rainforest.

These jungles aren’t tame. In their shadows roam elephants, boar, bears—and Malayan tigers. This big cat has become increasingly elusive as populations plummeted over the last century. This is the most endangered extant group of tigers, with less than 250 individuals left in isolated pockets of the southern, central, and northern Malay peninsula.

It is for them we had come together, eight Singaporeans, drawn from a variety of occupations—zoo researcher, future teachers, environmental engineers, retired principals— for a CAT (Citizen Action for Tigers) walk. My mother and I complete the spectrum, respectively as a not-for-profit consultant and aspiring conservationist. We were invited by my friend and mentor, Dr. Vilma D’Rozario, a former psychology professor and pioneering environmental educator who has coordinated CAT walks from Singapore for three years now.

These walks are the initiative of Dr. Kae Kawanishi, the founder of the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (MYCAT). She entered these forests for her PhD two decades years ago, leaving behind her two-year-old daughter. She devoted three years to near uninterrupted fieldwork, completing the first population study of tigers in Malaysia, with support from local park rangers and indigenous communities. When she emerged, it was with revolutionary data providing the first insights into the dynamics of big cats in the tropical rainforest, and a fierce commitment to their conservation in the patches where they still clung on.

We were driving towards one of the most critical pieces of this forest. Taman Negara National Park has long been recognized as a vital hotspot for tiger conservation. Two decades ago, the western end of the Taman Negara national park supported the densest population of tigers in Malaysia, with nearly two individuals per hundred square kilometres of forest. Then a decade later, the population crashed. Settlements and roads now all but separate the vast 130 million-year-old Taman Negara from Malaysia’s largest remaining area of montane forest, the Main Range, which runs the spine of the country. Western Taman Negara marks the only place where the two forests meet. This means western Taman Negara is also the only place where animals—like tigers—can cross between the normally separate populations, introducing vital genetic diversity.

But the size and inaccessibility of national parks like Taman Negara mean that it’s difficult for the already underfunded and understaffed wildlife department to establish firm ranger presences in the areas. As such, animals small and large, whether predator or prey, fall victim to cable snares set by poachers emboldened by the scarcity of anti-poaching patrols. With too little official presence to effectively control them, regulation—or at least a preventative presence—has to be supplemented by citizen action, like this CAT walk.

The car stops now, and we sleepily stumble out into the bright afternoon sun. As I blink into the light, I see we’ve pulled off the highway where it rises into a bridge with forest on either side. ‘Eco-viaduct’ reads the sign next to it, and we push through tall grass to reach it. One side is the Main Range, the other side is Taman Negara. This viaduct, which elevates the highway to create a passage underneath for wildlife to cross from one reserve to another—is the direct result of Dr. Kae’s advocacy to connect tiger populations in order to sustain genetic diversity. It’s also a sign we’re finally reaching our journey’s end.

Fifteen minutes later we pull into Merapoh, the small village that will become our home for the next two nights. Our accommodation is basic but clean and welcoming; we unload our bags and distribute ourselves. Walking outside, there’s so much more birdsong than I expected. My mother and I scan with binoculars for several minutes but succeed in focusing on nothing but rustling leaves, where there definitely was something a moment before. We’re so far from Singapore, and the isolation one feels from the rhythms of urban life is expansive and freeing.

That night for dinner we join Alex, MYCAT’s local representative, at the village restaurant. Over fried noodles and rice, he tells us about his work here. Originally from Manchester, he came upon MYCAT when a friend who had been on a CAT walk recommended the organization. Now he’s begun a rainforest nursery here for thousands of trees, providing employment for local Batek women to collect and raise saplings, as well as managing and leading those CAT walks that led him here three years ago. He interrupts the conversation several times to greet locals as they enter the restaurant for dinner, talking with them in rapid-fire Bahasa. When he comes back to our table, he explains that he’s telling them we’ve travelled all the way from Singapore to see these forests. We’re far from the inconspicuous group, all clearly foreign and unfamiliar with the area. Which is in fact the point. Our presence here as external observers is a deterrent to anyone considering casual poaching, and moreover, by staying in local homestays and eating in local restaurants, we reinforce a positive correlation between MYCAT and economic prosperity for the people in the area.

After dinner, we all climb into the back of Alex’s pickup truck for a night drive. We cluster like cattle, clutching each other to stay upright as he shoots off down the road, up and over the hills. To the sides of the vehicle, the dark is thick velvet, broken only by our weak flashlights. We rake the shadows as we pass from the edges of Taman Negara to palm oil plantation; each tree emerges alone and ghostly as if drawn only in pencil. Occasionally two pinpricks of light blink in surprise and we shout in excitement, banging the car’s windows to stop. Leopard cat numbers have grown at surprising rates in plantations—buoyed by booming rat populations, in turn, fed by the rich, oily fruit. We see three of them that night, slinking close to the ground. Their sleek bodies stain crimson in the red light of our torches: white light disturbs nocturnal mammals and can often bedazzle them for several seconds, startling them away. With the red light, the impact of our presence is muted, and we can watch as one cat watches us, licking itself lazily, self-assured in its mastery over the night. In the palm oil plantations, it is the primary carnivore. Nothing else is left to compete.

As we drive out the next morning, the forest looks very different. At the viaduct, Alex gives us a safety briefing—stay close by, don’t wander off, don’t scream if there’s a leech—and introduces us to our aboriginal guide before we set out to the starting point of our walk. Our goal today is to patrol for snares and signs of poaching, but also to gather some valuable data on the tigers. Tigers are never seen here: Dr. Kae, in twenty years, has never managed to find anything more than pug marks and scat. As such, the population is entirely documented through camera traps. MYCAT and the Wildlife and National Parks department, have set up several in the area over the past decade.

Barely a hundred meters in, we’re up to our knees in mud and much annoyed by leeches. At a river crossing, most of us choose to wade barefoot, after the first person in loses her slippers to the fast-flowing water. On the far side, we gingerly put on our hiking boots, trying in vain to dab off the worst of the mud with our leech socks, but generally resigning ourselves to damp feet. This is a jungle for animals, not people. We two-legged beasts must lumber noisily through the scratching branches and crackling leaves, with all the stealth of a marching band. Alex goes ahead with a machete, clearing a path, but still, I feel extraordinarily ungraceful as the sound of yet another twig snapping under my foot resounds through the forest horribly like a gunshot. As soon as we pause, however, the forest quickly reasserts itself. We watch the late morning light ring undisturbed through the canopy. Without the distraction of our tramping feet, we can hear the sounds grounding the space around us: the droning hum of cicadas, the mournful calls of gibbons, the steady trill of a distant sunbird.

Then we set out deeper. This jungle is unlike anything I’ve seen before. Most of the time there is no path for us to walk on and we have to push through dense undergrowth, our vision is constrained horizontally to the next few meters, and vertically to even less.

After an hour we breakthrough into a wide corridor cleared of vegetation, created for a line of electricity pylons that runs the length of the reserve. It’s our first chance to look up and, literally, see the wood for the trees. At the edge of the clearing, a white-handed gibbon perches on a dangerously thin branch, unfolding its preternaturally long arms and swinging down, tracing a neat semicircle in the air. The tree shudders violently as it lands. “You won’t be able to see this anywhere else in the forest,” Alex tells us. “Only in this clearing—where development has cut a clean, unnatural swathe—can you get a glimpse of the most forest-dependent species.”

The fact is that most life here takes place beyond the reach and sight of human visitors. As we walk, I get a sense of vast stories at play—tree fall and tree rise, predator and prey and life and death—to which we are tangential. I can’t shake the feeling of being an intruder, as if we’ve just interrupted something which will resume as soon as we leave.

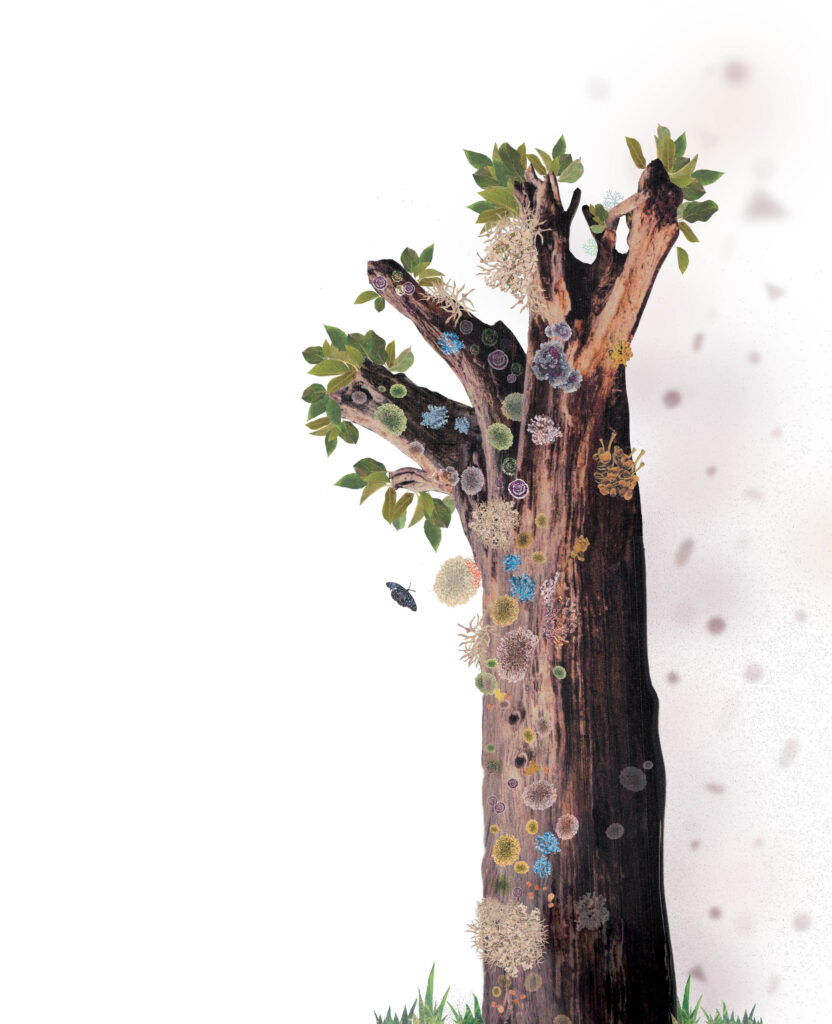

As the day passes, we catch glimpses of this larger picture. One tree is smeared with mud at about shoulder-level: a tapir had passed by. Another buzzes with sweat-bees issuing in and out of a small hole; on either side, the bark is raked with pale streaks—a sun bear tried to get at the honey, before giving up and moving away. The thick wingbeats of a rhinoceros hornbill echo through the forest, and my mother and I, through some unimaginable stroke of luck, happen to be standing at the exact gap in the trees to see it land. It’s immense and odd, the casque on its bill an unsettling shade of red. I turn around to get my camera, but it disappears in those two seconds. Once again, the life of the jungle has left us behind. A window, briefly opened, has closed once more.

Towards the end of the walk Alex shows us one of MYCAT’s camera traps. We come across it with a gasp—cutting through the dense forest, it’s so easy to forget that humans have come here before. The alien shape of the camera’s cuboid is a visual shock among the chaotic vines of the grove. It’s only with traps like this, Alex explains, that MYCAT can document the forest’s inhabitants. Blurry footprints aside, this provides the clearest picture, pun intended, of what lives here out of our sight—tigers and their prey, with luck—and direct the work on how to protect it.

As we walk away and out of the forest, I keep looking back at the trap. I try to picture the camera waiting here, the small eye of it, in sun and rain, night and day, watching for what passes. This is how we touch that other world we’ve come close to, but have never held in our grasp, all day. This is how we learn, rather than speculate; this is how we conserve.

After dinner and much-needed showers, we look through the photos from camera traps Alex checked earlier that week. No tigers. There are porcupine, though, as well as leopard cat and elephants. And as I examine the picture of a barking deer closely, I am hit by an intense wave of gratitude to have shared the same space as these remarkable creatures. I was where they were. I walked where they walked. As foreign as I felt in the jungle, we were, briefly, united by our paths.

The next morning we plant trees under the eco-viaduct. With luck, a tiger will cross from Taman Negara to the Main Range by this path every few years. That rate sounds low, but with the tiny size of the populations here, one individual crossing to mix its genes with those on the other side of the divide could make the difference between viability and extinction for the Main Range or Taman Negara tigers. Every handful of dirt we pack into the ground is a small step towards that. Shovel by shovel. Sapling by sapling. Alex describes how they imagine the viaduct looking in several years: a lush rainforest indistinguishable from the reserves on either side, the road running now beneath the highway uprooted and returned to soil. No sign that humans ever stepped there.

We set off back to Kuala Lumpur soon after, cramming muddy shoes into plastic bags and attempting to brush the worst of the dirt off our last pairs of pants. We cross the edge of the reserve and re-enter the palm oil plantations that will bring us most of the way back to the city. I think of what we have left behind: a small patch of fragile saplings, and even more intangible, the footsteps we left on our walk, somewhere deep in the forest. It’s hard to believe it will make a difference. There may not be a single tiger left here: even if there is, it could pass within twenty meters of a camera trap and MYCAT could miss recording it altogether.

It feels like an exercise in futility. But it is not: this is just one piece of the slow hard work of conservation. One group like ours coming every weekend will eventually build a population of support. Ten saplings planted every day will eventually build an unbroken stretch of green. This is an exercise in hope. We are putting our faith in the forest. We are believing in the resilience of its stories to keep playing, for the trees to prove larger than us once again.