Human-Wildlife Conflict (HWC) describes the clash between wildlife and humans. Typically, in these cases, humans infringe upon animal habitat in order to make a livelihood. Although this is commonly associated with agriculture, in Asia and Africa, the rapid expansion of urban areas also drives HWC. It is an all-too-common occurrence across the world today, with examples such as elephants destroying tea estates in Assam and Amur leopards being killed in retaliation for preying on livestock in Mongolia. In the large majority of instances of HWC, local and national governments tend to side with the humans in the conflict, with responses ranging from turning a blind eye to retaliation all the way to legislation detrimental to the wildlife involved. Resolution of HWC is by no means easy, inexpensive or quick; additionally, most resolutions tend to lead to adverse outcomes for humans or wildlife involved. Mauritius provides a classic example of a disastrous outcome of the HWC resolution.

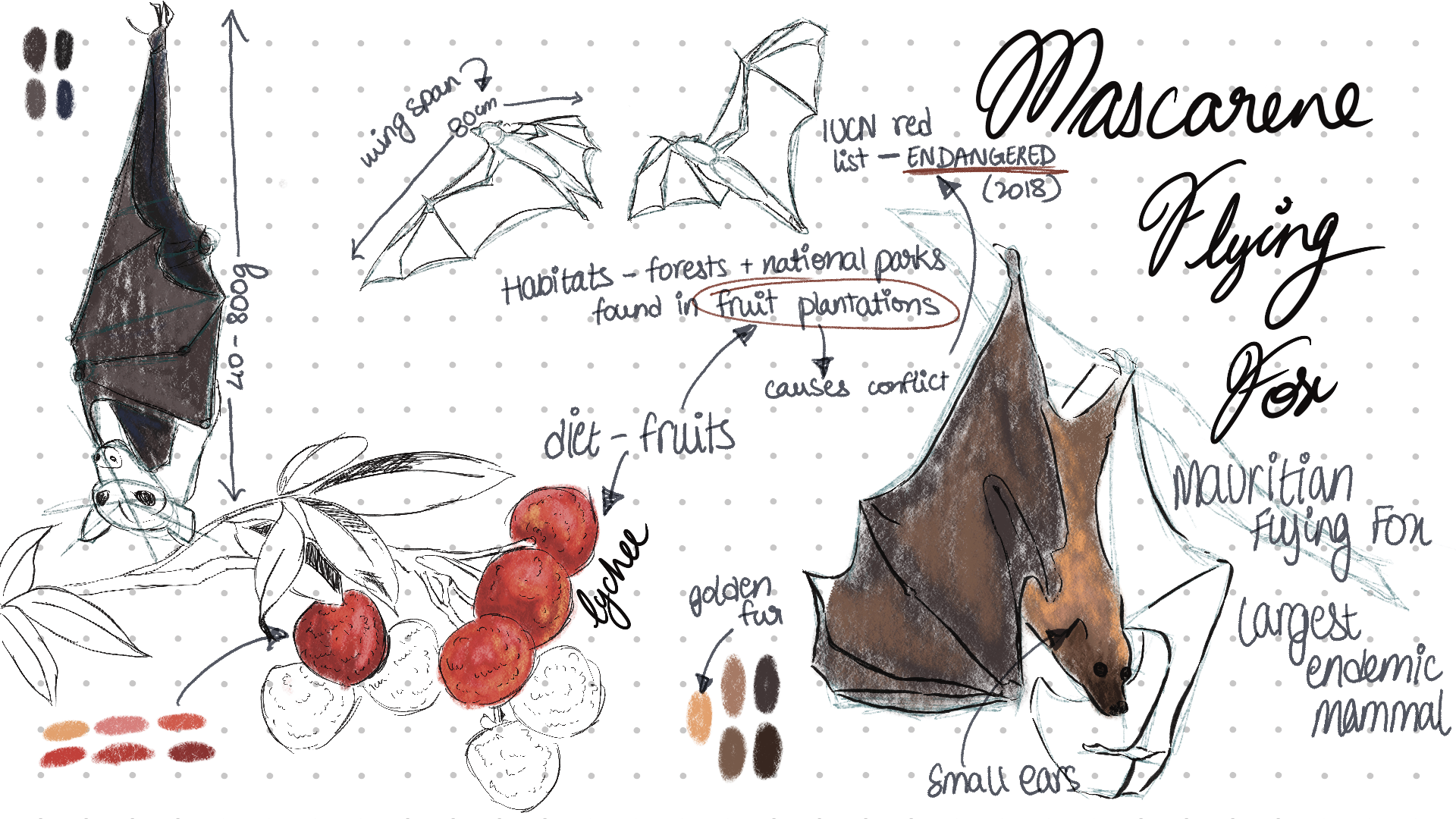

Mauritius is an island nation, east of Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean. It is made up of four islands and once famously housed the extinct dodo. It is home to a number of native species of animals and plants – such as the pink pigeon, the keel-scaled boa, the Mauritius ebony and the boucle d’oreille (the national flower of Mauritius) – many of which are threatened with extinction today. The Mascarene Endemic Flying Fox (Pteropus niger), the unfortunate antagonist in our HWC story, is currently listed as endangered by the IUCN. The reason for this conflict is that the fruit growers in Mauritius blame the species for reducing the yield of their mango and lychee crops. The IUCN Red List records show P. niger as rare in 1986, vulnerable between 1988 and 1996, endangered in 2008, vulnerable in 2013, and endangered in 2018.

Culling of P. niger in response to requests from the fruit growers dates back to 2006 when the Mauritian government recorded the culling of six flying foxes (although the government had authorised the culling of up to 2000 individuals). The original strategy of the government was to get the status of P. niger upgraded to vulnerable, and to pass a law authorising authorise the culling of species unless they were endangered or worse in response to the conflict, and to circumvent the current Mauritian law that forbade the culling of any species with a status of endangered or critically endangered. Hence, in 2013, the Mauritius government appealed to change the IUCN listing of the species from endangered to vulnerable in order. However, the revision of the conservation status for P. niger in 2013 was granted on the condition that it would be immediately reverted to endangered if culling was considered. Despite this condition, the Mauritius government undertook mass culling of P. niger during its breeding season in forested and protected areas in November-December 2015 (30,938 animals culled) and in December 2016 (7380 animals culled). The endangered IUCN listing of the species in 2018 is a direct result of these culls.

Following the 2015-16 culls, the government and the fruit growers expected the yields of mangoes and lychees to increase. To everyone’s surprise and shock, fruit yields, especially those of lychees, decreased markedly. The reasons for this are unclear; however, the fruit growers continue to believe that the losses in yields are caused by flying foxes and that the species needs to be culled further. The IUCN records the species’ current population at 37700 mature individuals, with losses of approximately 6000 individuals every year (to threats not including the culls). Another authorised cull on the scale of the 2015-16 culls would undoubtedly render the Mascarene Endemic Flying Fox extinct.

Mauritius changed its laws and carried out the culling of flying foxes not only in the absence of evidence of the effectiveness of the culling strategy in increasing fruit production and alleviating conflict but in the face of much evidence to the contrary. The 2015-16 cull was authorised despite evidence that it would only serve to further threaten the existence of P. niger. This case study presents a testament to the fact that evidence-based decision-making is crucial for conservation, often along with other forms of evidence such as past experience from management, and all the more relevant when species’ survival may be at stake such as in HWC situations. As various species of the flying fox threaten fruit production in a number of other countries, the precedent set by Mauritius is sobering and worrying.

Further reading

Florens, F. B. V., & Baider, C. (2019). Mass-culling of a threatened island flying fox species failed to increase fruit growers’ profits and revealed gaps to be addressed for effective conservation. Journal for Nature Conservation, 47, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2018.11.008