South of the Narmada River in eastern Madhya Pradesh, India, the Gond hill-village of Patangarh is the birthplace of a rich painting tradition. Adapted from the decorative mural techniques of the village, Gond painting depicts community folklore, creation tales, the verdant landscape, urban and pastoral lifeways, and more.

Though only four decades old, Gond art is widely appreciated as an intricate and evocative painting style. At its heart, Gond painting is about spirits and creatures deep in the forest that people have coexisted with for centuries. While Gond art has grown to encompass subjects extending far beyond field and forest, interdependence remains a lasting theme.

Gond painting as we know it today was first imagined and practiced by an artist named Jangarh Singh Shyam. In the early 1980s, he transposed the bitti chitra and digna practices of the village (wall and floor art, respectively) onto paper.

The act of creating a digna mimics the Gond story of creation: the great god Bada Dev spread mud on water to create the living earth, with trees, animals, and human beings. Dignas are painted by village women in the aangans (courtyards) of their homes, using a paste of lime and chalk. Bitti chitra is painted on the facades of houses, depicting Gond fables, deities, and legends. They are filled with colours made from mud or crushed flowers, changing with the weather and wind.

The original traditions of Gond painting, digna and bitti chitra, were materially and metaphorically connected with the earth. Jangarh Singh Shyam, who started painting on canvas, didn’t veer far from its roots. His works drew on Gond folklore and the symbolism of the forest. In Origins of Art: The Gond Village of Patangarh, Jangarh Singh’s nephew and regarded artist, Bhajju Shyam, writes:

“The tree has become one of the main symbols in Gond art. This is powerful art, because it combines the rendering of a tree with stories, concepts, and metaphors. Painting tree stories actually began with Jangarh chacha . Give him any size of wall and he’d cover it with trees! […] We all began by observing him and helping him with his work, so trees became a big theme for us as well.”

Jangarh Singh Shyam passed away under tragic circumstances in Japan in 2001, leaving a legacy of artists. Today, Patangarh is home to a number of painting families who were inspired by him. The village itself is painted, and scenes of coexistence—trees heavy with beehives, children chasing cattle, women collecting mahua flowers—find their way onto canvases, walls, and floors.

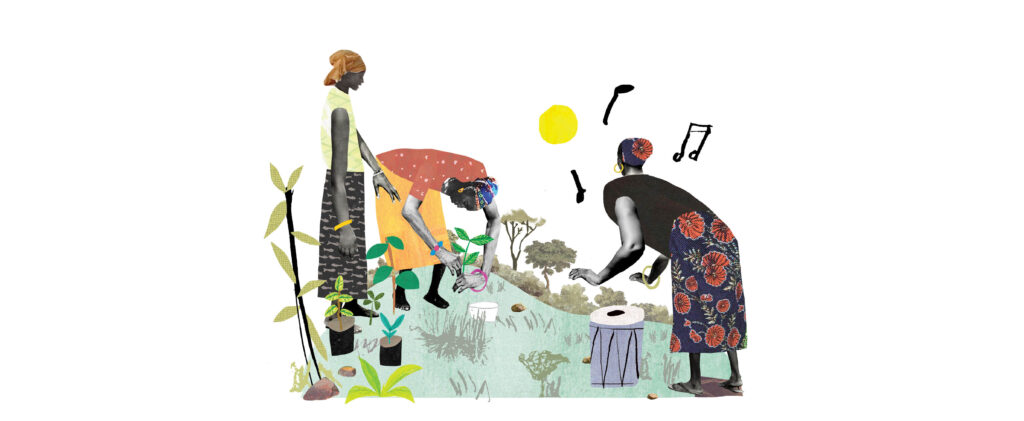

I met with Jangarh Singh Shyam’s grandson, Mithilesh Shyam. He and his wife, Roshni Shyam, are both artists. They invited me to Patangarh in May 2022, where they shared work from a collection on human-nature interrelationships. I was struck by the vivid colours and whimsical forms, by the seamlessness between human and non-human elements. Roshni and Mithilesh had worked together on each of these paintings. Their commentary gave insight into underlying messages and themes:

“In the monsoon of late August, we celebrate a festival called Hariyali [“greenery”]. Villagers wake early, gather their kulhad, tagiya, hashiya , and carry bamboo to the fields. We plant bamboo and pray to the earth, our mother goddess, heralding the start of the sowing cycle. Perhaps this is how humans first started planting trees.

The seeds of the first crop are sacrificed to family gods and goddesses—every community has its own. Since we are from the Shyam family, we pray to Sat Dev, the seven-headed god.

In my painting, you see a saj tree giving its leaves to a person and blessing his home with wealth and prosperity. We will eat in these leaves. Together, we will drink mahua and celebrate, singing karma dadariya and dancing to the beat of the madar .

I speak for trees because they can’t communicate in human languages. In this machine-filled world, humans can travel between countries and invent anything they dream up, but they remain dependent on trees. Trees, whose roots, leaves, and branches have so many worlds in them, are the keepers of the earth. When we clear the forest, we experience droughts and floods. Clouds and rivers weep and the soil can’t hold their tears, so we drown. We must save the forest. This is what I urge through my painting.”

I was moved by their conviction. The paintings are suffused with tenderness, revealing the ecocentrism of the Gonds. The graceful, flowing compositions and anthropomorphic figures convey exchanges between humans and the forest, making interlinkages apparent.

As we spoke, their daughter, Damini, stood on her toes and listened intently. When Roshni and Mithilesh had finished, she asked if she could add something.

“The eyes are always filled in last,” she grinned, pointing at her own. Why, I asked. Against a striking backdrop of birds and trees, Damini answered, “Then the painting comes alive.”