Feature image: Participants from the study—representing multiple generations of the Ngāti Rangi—going out to test biocultural monitoring tools, with their sacred mountain Ruapehu in the background.

Note: The following text is described in the Ngāti Rangi mita (dialect), while concepts may be similar eg: Mouri = Mauri, the spelling reflects the tribal vernacular.

In Aotearoa (New Zealand), the Department of Conservation’s biodiversity strategy implementation plan—Te Mana O Te Taiao—published in 2022, prioritises addressing the drivers of biodiversity loss. Importantly, this strategy identifies the need for integrated approaches that incorporate Te Ao Māori (the Māori world) knowledge and systems.

Cultural-ecological constructs are key in relationships between Indigenous people and their environments. Biocultural approaches can contribute to reversing the current biodiversity crisis. Furthermore, the emphasis is on tools that can collect information to inform biodiversity protection with consideration for their environmental, social, cultural, and economic impacts. In our study, we developed a tool that is a step towards achieving these national goals.

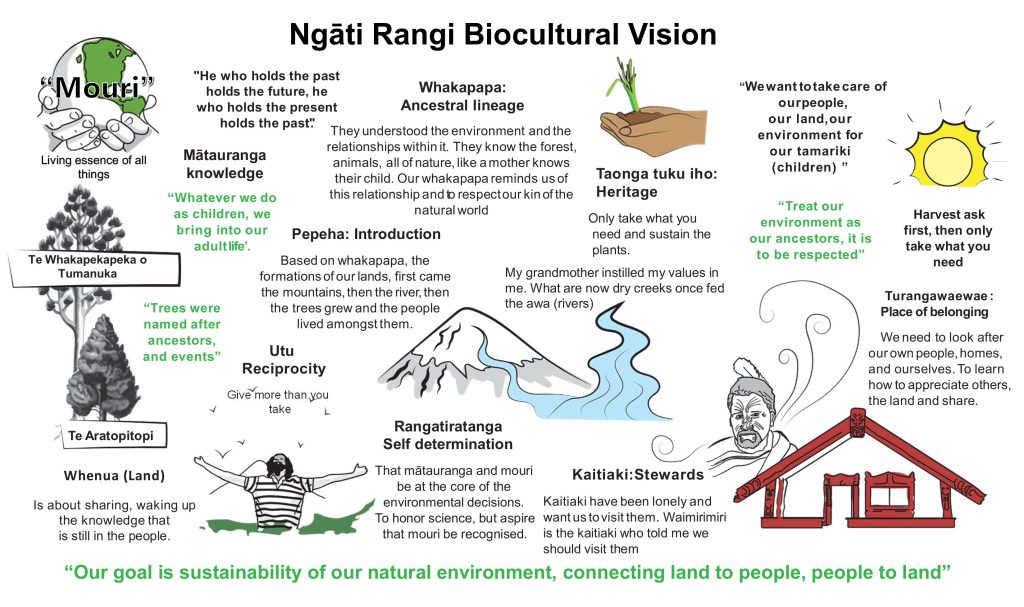

We explored a biocultural monitoring tool based on mātauranga (Māori knowledge) to inform Ngāti Rangi (a central North Island Māori tribe) about the health of spatially separate but ecologically similar forests within their tribal estate. Here we report on the Ngāti Rangi example of parametrised metrics for forest health, embedded in their worldview, and how this expression supports the Ngāti Rangi’s assertion of rangatiratanga (self-determination) in their co-management aspirations.

We conducted a series of noho taiao (community workshops) and one-on-one interviews to collect values that express a Ngāti Rangi worldview, to measure the health of the ngahere (forest). Gradients and indicators were developed to apply as a measure of forest health. The interviews provided an observation of ngahere health and assessed inter-generational differences in how it’s perceived.

Rongoā (medicinal plants), manu (birds), ahua o te ngahere (nature of the forest), wai (water), and tangata (people) were themes prioritised by the Ngāti Rangi. An example of the metrics that the tribe wanted to measure was captured in Question 8: are there any significant trees present? This was related to significant roosting locations—such as that of their taonga or sacred bird species in the area—and cultural or spiritual practices that were held at these trees. This metric allowed the tribe to record the tree’s location, its name, and the use it was traditionally known for. This was recorded as either presence or absence, with the option to make notes on its significance and cultural heritage.

Another example of culturally important information was encapsulated in Question 13: what is the rongo of the wai in the ngahere? The rongo in this instance is related to the vibration or sound that the water makes, in relation to its interface within the forest. This was measured using a metric called mauri ora—the essence of healthy living—where key taonga species were abundant in quantity and diversity, receiving a ranking of ‘3’. The next rank ‘2’ reflected a reduction of the previous observations at each stage, until the metric reached ‘0’ or mouri te rongo, where the mouri was seen to be inactive or in a state of revealing or uncovering its living essence or vitality. At this stage, an absence of significant species and an overall decline in species diversity, presence, and vitality were observed.

The above cultural tenets were considered the most relevant traits of a forest thriving from a cultural perspective. Through our study, we demonstrated a biocultural monitoring tool as one facet that the Ngāti Rangi can use to reconnect, reclaim, and build new knowledge around their forests. Biocultural approaches are an opportunity to reverse not just ecological declines but also socio-cultural impacts from colonial legacies.

These understandings exemplify what a biocultural approach can look like in place. A full sensory evaluation of forest health facilitating a deep relational connection to place, coupled with philosophies such as reciprocity and whakapapa (genealogical hierarchy highlighting connection to the environment through kinship relationships) are vital features of a biocultural conservation approach.

Further Reading:

Reihana, K. R., O’B. P. Lyver, A. Gormley, M. Younger, N. Harcourt, M. Cox, M. Wilcox et al. 2023. Me ora te Ngāhere: visioning forest health through an Indigenous biocultural lens. Pacific Conservation Biology 30: PC22028. https://www.publish.csiro.au/PC/PC22028.