Feature image: Sendi showing off the growth of a rose coral (Montipora capricornis) he ‘revived’ after securing a new piece of coral to an old one.

Coral is part of everyday life in the Maldives. On the surface, coral is found nested inside the walls of traditional homes, in the sediment and pigments used to make these walls, and the brave even add coral powder to dufun—areca nut chewed with betel leaves and spices—for a little flavour kick. Underwater, coral reefs shape the geography of Maldivian atolls and are fundamental for ocean livelihoods. They protect islands from waves and erosion caused by climate change, while coral fragments eventually become sand, allowing islands to withstand sea level rise without diminishing to smaller strips of land. In the middle of the Indian Ocean, where resilience is crucial for survival, life cannot be conceived of without coral reefs.

The various forms in which Maldivians perceive and know coral reefs offer a glimpse into the islanders’ rich understanding of and coexistence with these underwater formations. In Dhivehi —the official language of the Maldives—there are over 25 different words for a reef. A thila describes a formation that is deep enough to go over it, while giri refers to a coral reef that is not connected to the main reef and can go up to shallow waters. Badhi stems from the Dhivehi word used to describe a coconut shell used to collect coconut sap and refers to arm-shaped reef formations that come out of the reef’s main wall. Muravi is a single species of coral that can grow so big as to be called a reef in itself, and the list goes on.

Yet, coral history in the Maldives is long and complex. After the first resort opened in the country in 1972, land reclamation became a common practice for tourism development. When land is reclaimed, stretches as long as 400 hectares of reefs are covered with sand to be built on. Our land-based view of ecocide fails to explain the impact caused by the destruction of entire coral reefs and the resulting loss of marine biodiversity. In the aftermath of reef destruction, ‘coral restoration’ has become a go-to measure to attract marine life to areas where water contamination and over-exploitation have degraded reefs to the point of gloomy rocks.

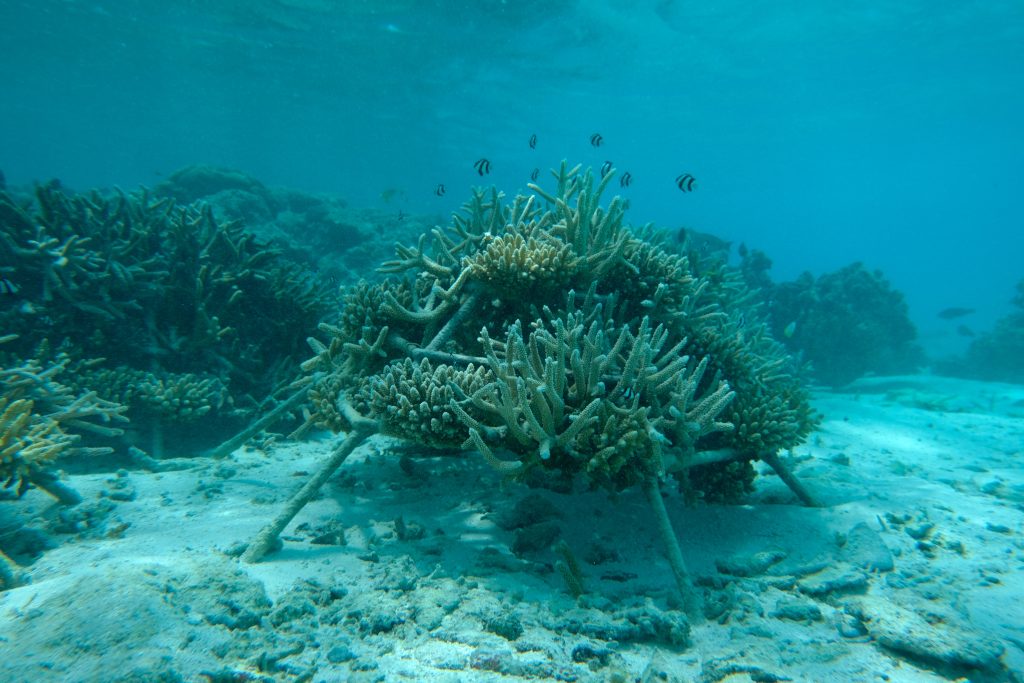

In the Maldives, coral restoration is commonly carried out with so-called ‘coral frames’. Spider-like metal frames are introduced into shallow areas, and live coral clippings are attached to the frame. Despite the seemingly good intentions, the environmental impact has to be considered in what has now become a rapidly growing underwater business industry.

Coral restoration using metal frames depends on continuous human intervention, and if frames are not properly maintained, they quickly become artificial structures remaining in the ocean. Fast-growing corals—such as those in the Acropora genus—are most commonly attached to the metal frames. The long-term success of this method and coral survival are still to be proven. Sendi, a seasoned ocean activist and professional dive instructor since 1981, describes the introduction of coral frames to ocean floors as “importing an alien species of bird and releasing it onto an island”. To this day, hundreds of metal frames have been deposited on Maldivian ocean floors, many of which have quickly become underwater metal cemeteries.

Aesthetic concerns aside, the introduction of an artificial structure into a delicate natural marine environment can affect broader ecological dynamics. For instance, an external coral barrier made of metal frames that is placed in an olhu—a natural shallow reef bay—can have impacts on marine life and humans alike. These structures can alter tide and nutrient flows, which has knock-on effects on the foraging habits of fish. Local fisherfolk, who follow an olhu’s natural cycles, adjust fishing times according to the tide and time of the day when bigger fish enter the bay. A seemingly small change to a natural bay’s structure can have large effects on marine life and the people who rely on them.

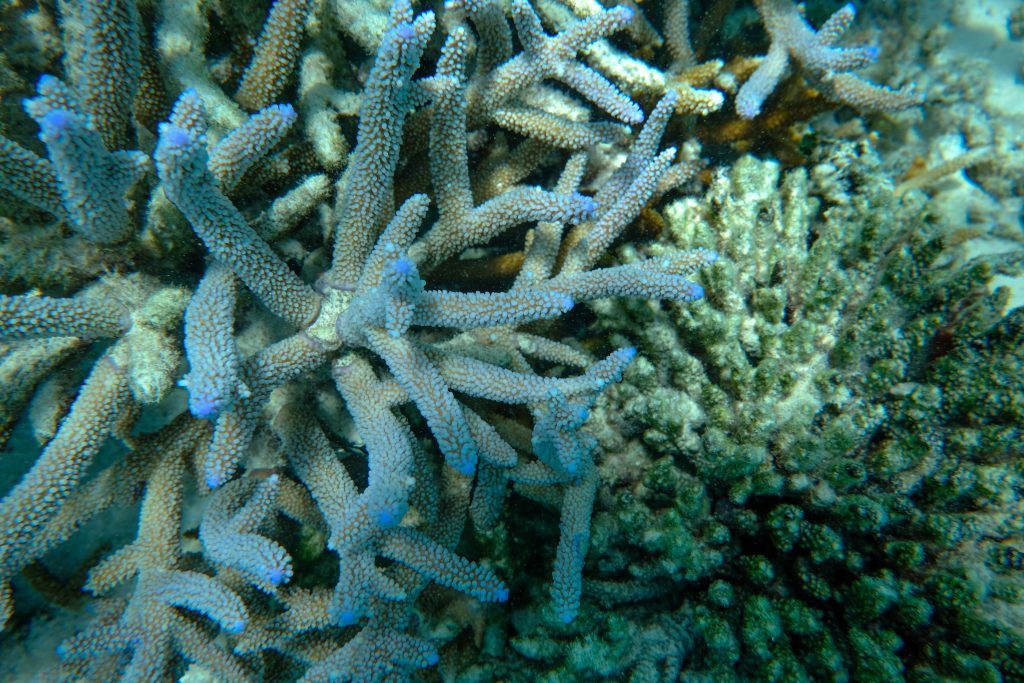

Full of intricate patterns and unparalleled colours, a Maldivian coral reef can support up to 300 different coral species. Solutions to improve, conserve and promote coral growth must be locally adapted to each reef’s specific structure and species. Instead of restoration, we propose coral revival, where consideration for the entire marine ecosystem and its linkages with broader environmental factors are given priority.

Much like endemic reforestation—where special attention is given to native spaces and ecosystem restoration—coral revival takes various forms but primarily focuses on using local coral varieties to restore dead or dying sections of the reef. This method respects the reef’s original location and involves attaching live coral to decaying or dead coral structures. Common techniques include using ropes, marine cement plugs,or low-voltage electricity* to ‘nurse’ corals before transplanting them to existing reefs. (*Studies have shown that using an electrical current can stimulate coral growth.)

Across the Maldives, different coral revival initiatives are underway, experimenting with the specific types of coral and water conditions in each location to ensure the maintenance of the reef’s delicate balance. Following the classic Maldivian mantra of “leave nothing but bubbles”, coral revival relies on local ecological knowledge, which must be integrated into research and restoration efforts.

Although coral restoration initiatives have their limitations and cannot replace the urgent need to reduce environmental stressors—such as ocean acidification due to increasing carbon dioxide emissions—a reef-by-reef approach that integrates local communities’ deep ocean knowledge will be crucial to the success of ongoing Maldivian efforts to conserve and preserve unique coral species.