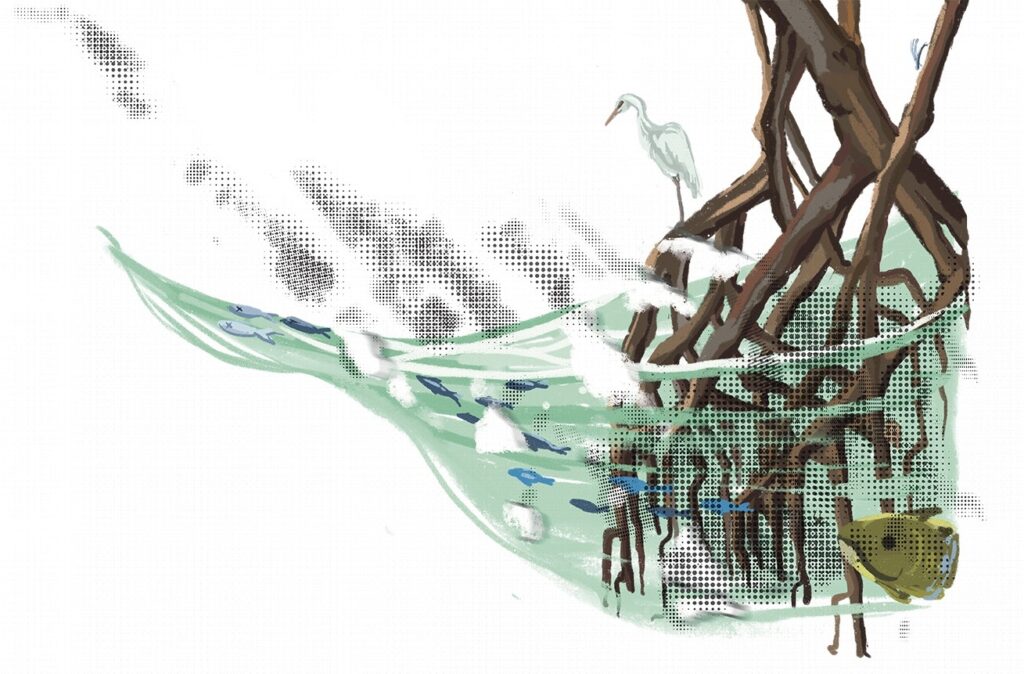

Blue carbon refers to the carbon dioxide stored within vegetated coastal and marine ecosystems, such as mangroves, saltmarshes, and seagrass meadows. The term first emerged in the United Nations Environment Programme 2009 report titled Blue carbon: The role of healthy oceans in binding carbon.

Studies show that although blue carbon ecosystems only constitute only 2 percent of the ocean area and 5 percent of the global land area, they are significant natural carbon sinks, accounting for nearly 50 percent of all carbon buried in marine sediments. The carbon removal efficiency per unit of the blue carbon ecosystem is supposed to be five times higher and its absorption capacity three times faster than tropical forests.

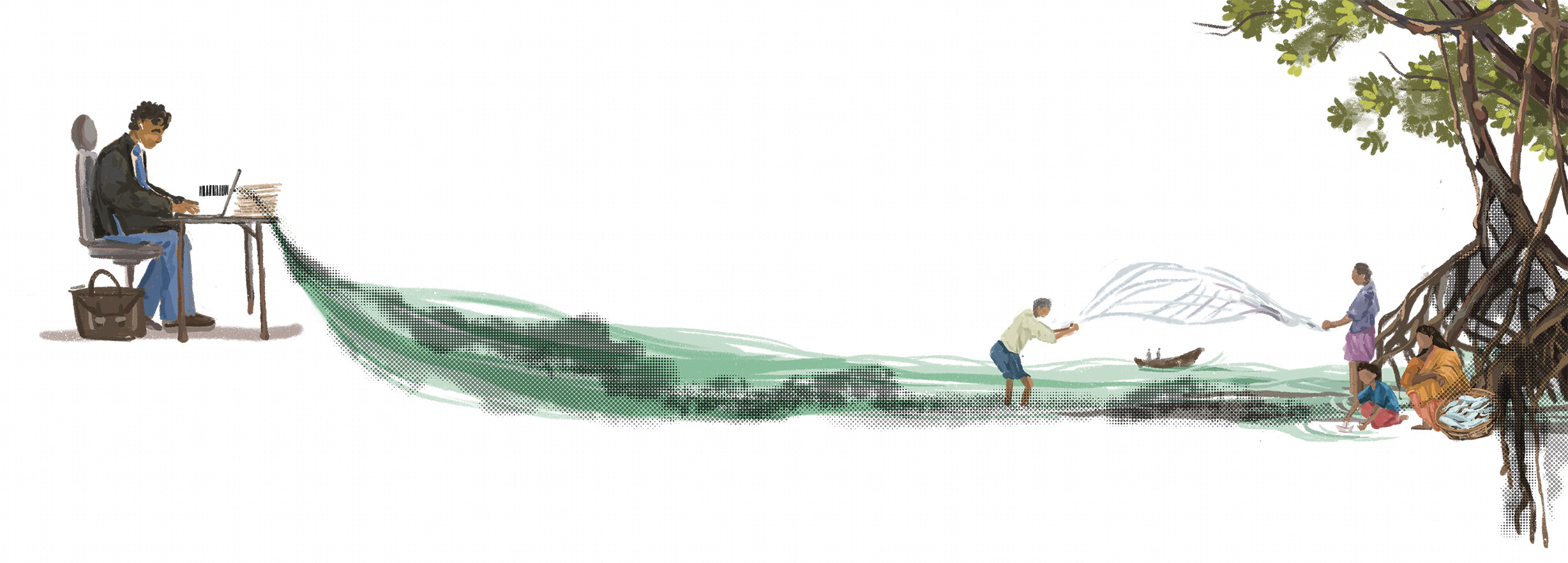

Blue carbon ecosystems as nature-based solutions have the potential to address both climate mitigation and adaptation challenges at relatively low cost, while delivering a range of co-benefits for people and nature. But while there is a strong acknowledgement of the importance of conservation and governance by scientific communities, policymakers, market players, and proximate community groups, these ecosystems are fast degrading.

It is estimated that more than 50 percent of saltmarshes, 35 percent of mangroves and 29 percent seagrass meadows have been lost since the mid-20th century. The loss is attributed to climate-induced impacts, such as sea level rise and extreme weather events, as well as coastal development action. When these ecosystems are degraded, they not only fail to act as carbon sinks, but also contribute to carbon emissions by releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere. With a global annual loss of blue carbon ecosystems between 0.7 to 7 percent annually, it is projected that these ecosystems are releasing between 0.15 and 1.02 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year, contributing significantly to anthropogenic climate change.

Recently blue carbon has received enormous global attention for climate action. The 16th climate COP (Conference of the Parties) in 2010 specifically accorded high importance to blue carbon ecosystems in this context. Subsequently, international and national policy instruments—including Nationally Determined Contributions, which are national climate action plans under the Paris Agreement, with the aim of limiting global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels—place stronger emphasis on blue carbon opportunities.

The recent trend is also skewed towards widespread commodification of marine resources, mainly through blue carbon markets. On the one hand, initiatives patronised by environmental conservation organisations and private sector groups, such as Blue Carbon Buyers Alliance, are advancing an exclusionary conservation agenda. On the other hand, large-scale investments through Blue Economy initiatives are altering existing social-ecological relationships within these blue carbon systems.

This article outlines two broad contours of blue carbon governance that include: (1) complexities arising out of the commoditisation1 of blue carbon areas, with an exclusive focus on carbon in global trade (2) changing social-ecological relationships in terms of distributional, procedural, and recognitional justice issues for local communities (see footnotes).

The carbon tunnel vision trap

The financialisation of ecosystem services, especially of aggregate carbon values through the carbon market, is one of the dominant pathways to promoting climate action. The product value chain approach with a buyer-centric market system is plagued with competing interests and power imbalances in favour of buyers and system facilitators, and is characterised by misuse by actors who are not the stewards of the blue carbon resources. Markets are also unclear about the true valuation of co-benefits such as coastal protection, disaster proofing, and local livelihoods associated with blue carbon systems.

“Carbon tunnel vision” also limits the capacity to design and deliver cross-sectional climate action with a holistic view of biodiversity conservation, habitat protection, human rights, and well-being considerations. It deepens the trap of scientific, sectoral decision-making which at times lies at cross-purposes with other dimensions of climate adaptation and mitigation action.

There has also been a growing interest in formulating legal mechanisms that commodify, monetise, maximise, and merchandise the marine environment’s carbon sequestration services, as well as a justified growing concern over these proposals. There are plenty of incidents where this reductionist view of climate action is generating serious social-ecological consequences. And while there is a great thrust on geo-engineering climate solutions in marine spaces, the impacts on coastal systems such as fisheries, seagrass areas, and mangrove forests are yet to be evaluated.

Greenwashing is quite common in the absence of appropriate mechanisms for proper valuation of blue carbon resources, including its co-benefits. In their 2024 study, Achakulwisut et al. state emphatically that it is time to move beyond the “carbon tunnel vision” demonstrated in widespread greenwashing through so-called carbon neutral oil and gas projects. Their scholarship highlighted the serious negative impacts of these projects on biodiversity, fisheries and blue carbon habitats, alongside the violation of human rights in Latin America, Africa, and North America.

Similarly, there is ample evidence of forest fishers in the Sundarbans facing “double marginalisation” from fortress conservation in marine protected areas, accentuated by extractive blue carbon projects. This results in increasing restrictions on local communities entering the forests for fishing and the collection of golpata (leaves of the Nipa palm, Nypa fruticans) and honey.

Equity and social justice

Blue carbon ecosystems are spread across areas where coastal communities, small-scale fishers and Indigenous Peoples live. These diverse peoples directly rely on these resources for livelihoods, food and nutritional security, and well-being. These systems are where different land and aquatic resource tenures/rights intersect and underpin the sustenance of global aquatic food systems. Despite a proclaimed ‘focus on social equity’ as part of broader Blue Economy discourse, much of the attention on blue carbon and the ocean (or blue) economy currently focuses on aspects of economic viability, ecological sustainability, and technological innovation. There is little attention given to issues of procedural, distributional and recognitional justice2 . At worst, it represents an expansion of green colonialism.

A global scan of technical guidance documents on blue carbon markets, their governance, and investment, undertaken by a group of scholars led by Sarah Lawless, reveals a superficial consideration of tenure aspects of small-scale fishers. Of the documents they reviewed, some recognise access and management rights of the local communities to certain extent. However, very few recognise withdrawal rights (the right to withdraw or harvest resources within the area to which tenure extends) and exclusion rights (where rights-holders lawfully exclude or ban others from using certain resources and accessing areas). In fact, none of this guidance even acknowledges transformation rights (the ability to change the land—area and resources—so that it has a different use).

Further market mechanisms such as the long carbon credit retirement timeframe3 , limitations of transaction length (which determines the delivery obligations placed on local communities), and ambiguity and lack of transparency in penalty clauses for protection lapse, further weaken tenure rights and tilt the power in favour of carbon market actors.

According to Global Atlas of Environmental Justice (EJAtlas), environmental defenders, especially from Indigenous and other marginalised groups, face high rates of criminalisation and physical violence across different geographies of the world. Incidents of criminalisation of non-timber forest product collection in Sundarbans, timber collection for firewood, and fishing by small-scale fishers in marine protected areas which are potential blue carbon markets, cause rising tension between traditional users of resources and blue carbon proponents.

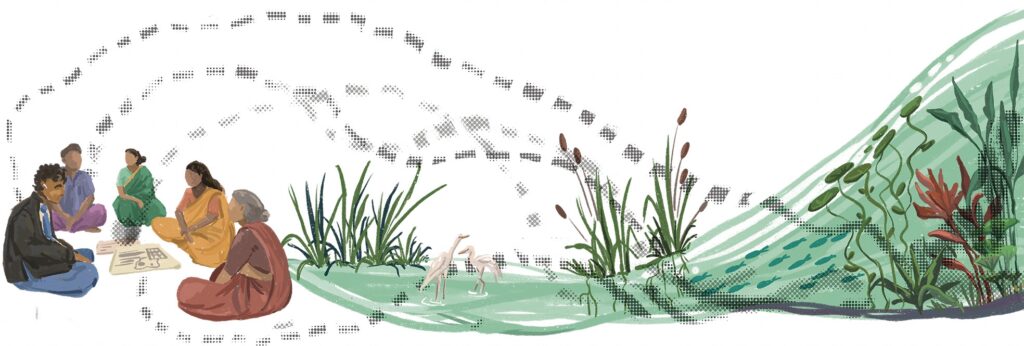

The literature also suggests that the complexities of blue carbon ecosystems are not simple to address. Social science scholars argue that recognition of tenure in the early stage of a blue carbon project is important. However, the formalisation of tenure—unless founded on principles of deliberation, community partnership, co-production, recognition of customary and full rights to resources, and addressing historical inequalities—may not result in fair and distributional justice in favour of coastal communities and local fishers.

While procedural, distributional and recognitional justice concerns are quite evident, there are some positive examples that are more optimistic about improved community agency in the governance of blue carbon systems. For instance the Vonga Blue Forest Project in Kenya demonstrates a collaborative approach with legislation recognising community co-management and a greater appreciation of community livelihood co-benefits and biodiversity conservation. Similarly, the community-based management of seagrass and mangrove ecosystems in the Philippines, promotes blue carbon ecosystem management through traditional governance practices and the active involvement of local communities and fisherfolk associations.

Paradigm shift

The growing interest in the transformation of blue carbon ecosystems into marketable carbon assets represents a profound shift in how these resources are valued and governed. These governance transitions are not merely technical adjustments but entail significant redistribution of wealth and decision-making power. Rather, they raise fundamental questions about who controls, benefits from, and has access to coastal resources that have traditionally supported local livelihoods through fishing, tourism, and cultural practices.

Current blue carbon market frameworks exhibit significant inadequacies with their failure to appreciate complex tenure systems intersecting with formal and informal governance arrangements, and a lack of equitable benefit sharing and the persistence of the carbon tunnel vision. The market structure often fails to account for traditional resource tenure systems and the customary rights of fishers and coastal communities. This carries the risk of disrupting existing social-ecological relationships, which often manifest as reduced food security, loss of income, cultural erosion, and even displacement from ancestral territories and increased threat to conservation.

The ethical challenges of blue carbon markets are exacerbated by power asymmetries between the global actors who design these systems and the local communities expected to implement them. There is an absolute reliance on scientific knowledge about carbon sequestration, and technical requirements for monitoring, reporting, and verification often exceeding local capacity without substantial external support. These structural inequities suggest that without significant reconfiguration, blue carbon markets risk reinforcing rather than addressing existing patterns of environmental injustice.

Like other nature-based climate solutions, blue carbon requires the transformation of social and cultural relationships—between private and public actors, local and global finance, and scientific and other knowledge systems. There is a need to move beyond superficial community engagement to concrete actionable approaches. Common phrases include “establishing partnerships”, “improving community knowledge”, and “undertaking stakeholder engagement”—terms that lack specificity regarding implementation mechanisms, power-sharing arrangements, or measurable outcomes.

The shift in market behaviour and blue carbon governance requires institutional innovation and policy reform. The academic and policy communities must also address the disconnect between blue carbon initiatives and the substantial body of knowledge on community-based natural resource management developed over decades. Effective engagement strategies should draw on proven approaches from related fields, such as community forestry, co-managed fisheries, and Indigenous conservation territories, rather than treating blue carbon as an entirely novel domain requiring new engagement paradigms.

- Commoditisation is a term that refers not just to the commodification of an entity (adding a price to a product), but involves processes of its standardisation coupled with a focus on interchangeability across different producers and buyers ↩︎

- Procedural justice refers to the level of participation and inclusiveness of decision-making, and the quality of governance processes. Distributional justice can be defined as fairness in the distribution of benefits and harms of decisions and actions to different groups. Merely procedural and distributional justice will not serve their purpose unless combined with recognitional justice. Recognitional justice provides for the acknowledgement of and respect for pre-existing governance arrangements as well as the distinct rights, worldviews, knowledge, needs, livelihoods, histories, and cultures of different groups in decision-making. ↩︎

- A carbon credit retirement timeframe refers to the period of permanent removal from the carbon registry and restriction of further circulations. ↩︎

Further Reading

Achakulwisut, P., P. C. Almeida and E. Arond. 2022. It’s time to move beyond “carbon tunnel vision”. SEI Perspectives. https://www.sei.org/perspectives/move- beyond-carbon-tunnel-vision. Accessed on April 25, 2025.

Atchison J, Foster R, Bell-James J. 2024. Blue carbon as just transition? A structured literature review. Global Sustainability 7: e27. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2024.24.

Vierros, M. 2017. Communities and blue carbon: the role of traditional management systems in providing benefits for carbon storage, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods. Climatic Change 140(1): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0920-3.