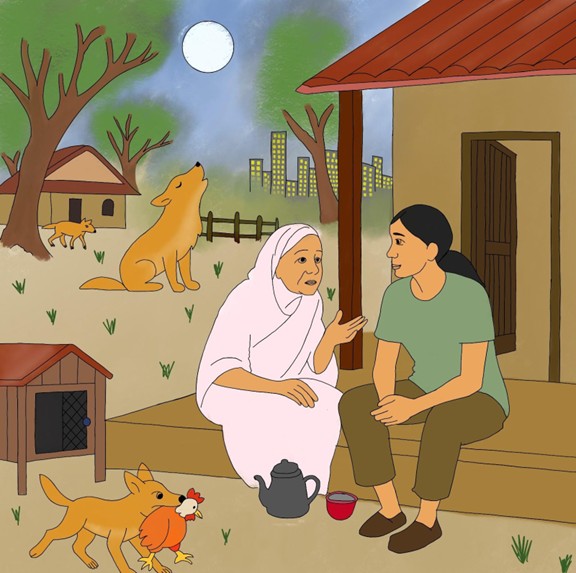

(Illustration by Snigdha Bhagawatula)

I was walking through the streets under the scorching sun. Suddenly, my gaze fell on an aita, an elderly woman, sitting on the threshold of her home. As soon as our eyes met, she smiled and gestured for me to come closer. I introduced myself as a wildlife researcher and told her I had come to speak with her. She welcomed me warmly and began recalling how the place looked some 30-40 years ago.

“Jackals?” she said, her eyes lighting up with memory. “Back then, this whole area was full of trees and wild vegetation. There were only two or three houses around. And on chilly winter evenings, around six o’clock, the jackals would start howling. They even came into our front yard and we could see them clearly in the moonlight.”

As she spoke, weaving memories into vivid threads of nostalgia, I sat there thinking about how powerful it is to listen to these stories. This was during my fieldwork in Assam, India. I had set out to understand how people perceive species such as jackals—once commonly seen, but rarely heard or spotted now.

Assam is a land where wildlife is deeply embedded in the culture. Jackals too have long been associated with its storytelling traditions and folklore. Growing up in this state, I often heard stories about jackals, such as how they would sneak into villages to snatch poultry. Consequently, people would chase them off, sometimes throwing sickles or knives. One story that stayed with me was about a jackal who lost its tail during such an encounter, which gave rise to the image of the “tailless jackal” famous in Assamese folktales.

These stories made me wonder—were such narratives grounded in real-life interactions? With the spread of urbanisation and shrinking natural habitats, are younger generations still aware of these tales?

Oral traditions

Although considered ecologically resilient on account of their wide distribution and flexible diet, golden jackals are vanishing from places across India that they previously occupied. Habitat modification, intensive agriculture, urbanisation, fatal vehicular collisions, hunting, interactions with free-ranging dogs, are some of the threats faced by this so-called resilient species. And populations are now only found in fragmented patches.

As I continued speaking with people across different age groups from urban, peri-urban, and rural areas, I began collecting beautiful oral narratives that featured the xiyal (jackal) in everyday life. These included poems, lullabies, idioms, and stories.

“Xiyali ei, nahibi rati, ture kaney kati logamei bati. Kaankati murote moruwa phool, Kaankati palegoi Rotonpur.” In this lullaby, a mother warns a jackal not to come at night to disturb her child. If it dares to come, she says, she will cut off its ear and use it as a wick for her oil lamp. She goes on to describe the jackal wearing an imaginary flower on its head. The jackal is then said to be walking far enough to reach an imaginary village (famous in Assamese tales) called Rotonpur. Though sung playfully, this lullaby conveys subtle cues of human-jackal interactions and instils a fear of jackals in young children.

Another children’s rhyme goes: “Rod dise, boruxun dise, xora xiyal r biya, ghonsirikai tamul katise, amak-u olop diya.” It translates roughly to: “If it’s raining and sunny at the same time, then it’s the tailless jackal’s wedding. The sparrows are cutting betel nuts. The guests, including humans, request them to share some nuts.” The poem anthropomorphises jackals and links them with cultural practices in Assam such as betel nut chewing, and associating their presence with certain weather events—even if not ecologically grounded.

Proverbs, too, reflect the jackal’s place in Assamese life. One saying goes: “Xui thaka xiyal e haah dhoribo nuare”, a very common sarcastic dialogue used by Assamese parents. It translates to “A sleeping jackal can’t catch poultry”, implying that laziness leads to failure. But this expression also reveals ecological knowledge that jackals prey on poultry or birds.

“Siyale soru suwte, kukur motyote nai” is used when someone tries to blame another for something they didn’t do. It likely arose from lived experiences. In the past, jackals would sneak into kitchens that were made of bamboo and mud, sometimes picking up or eating from clay utensils. If the animal wasn’t seen, dogs were blamed. But the elders would say, “There were no dogs in the village then, it must’ve been a jackal.”

Older respondents also shared how, in the past, dogs were domesticated specifically to deter jackals. Stories by Lakshminath Bezbaruah in Burhi Aai’r Xadhu (Grandmother’s Folktales), often portrayed jackals as clever tricksters or wise animals. It shows their dynamic relationships with humans and other animals. These stories, while entertaining, also served to normalise human-animal coexistence, inflict moral values, and pass on ecological understanding, especially to children.

As I continued my fieldwork, one observation stood out clearly: perceptions of jackals varied greatly across generations. When I interviewed younger adults, a common pattern emerged. They had heard of xiyal, but many were unable to identify the jackal when shown a photo. Some recalled hearing jackal howls during their childhood. However, they also said such occurrences had become rare in recent years in the cities. Interestingly, most of them were familiar with jackals more through oral stories than real-life encounters. Many expressed concern over habitat loss and felt that jackals were disappearing due to rapid environmental changes. They believed that jackals and other wildlife in shared spaces should be protected. In addition, they also suggested nature education is important for raising awareness.

When I spoke to children, especially in urban areas, the connection had shifted even further. Most had never heard oral narratives about jackals. Their knowledge came primarily from textbooks or YouTube videos. In peri-urban and rural areas, some children had seen jackals but often expressed fear or disinterest. Many felt the species belonged inside forests and should not be near human settlements. The emotional and cultural familiarity, and ecological knowledge about jackals as predators or scavengers that older generations had seemed to be fading.

Precious connections

This whole experience made me realise that the conservation of species is not only about counting them and mapping habitats—it is also about listening. Narratives are valuable repositories and an important part of culture. Shaped by knowledge, experience, and beliefs, they provide a window to understanding the interconnectedness between human and more-than-human worlds. They also enable us to think about and make sense of social structures.

Further, narratives tell us how people historically observed and interpreted wildlife behaviour, as well as how they perceive and value the natural world. They can foster empathy and tolerance towards wildlife, or sometimes reinforce fear, hatred, or indifference. In communities across Assam, jackals live not just as biological entities, but as characters reflecting what Nabhan (1997) once called “cultures of habitat”.

During my interactions, I began to sense that as cities grow and daily life becomes more fast-paced, people’s connection with nature is gradually diminishing. Narratives were once a bridge between generations and between humans and non-human animals. But as they fade, it signals not only the loss of stories, but a form of knowledge that has long helped humans to coexist with non-human species. For culturally significant but overlooked or common species, oral narratives can help rekindle people’s emotional connection and build awareness. While digital platforms such as YouTube and children’s books attempt to recreate some of these narratives, their reach remains limited. Many traditional stories are not documented at all and get lost with time.

As a researcher, I have found oral narratives to be excellent icebreakers. Especially when approaching communities where people are often busy or hesitant to participate. Asking about folklore or cultural beliefs often stirred a sense of nostalgia and pride, making people more open, engaged, and willing to talk. Thus, in a world racing ahead, listening to forgotten stories can perhaps help us find our way back to our roots.

Further Reading

Bhatia, S., K. Suryawanshi, S. M. Redpath, S. Namgail and C. Mishra. 2021. Understanding people’s relationship with wildlife in Trans-Himalayan folklore. Frontiers in Environmental Science 9: 595169.

Nabhan, G. P. 1997. Cultures of habitat: On nature, culture, and story. Washington DC: Counterpoint.

Shawon, R. A. R., M. M. Rahman, S. O. Dandi, B. Agbayiza, M. M. Iqbal, M. E. Sakyi and J. Moribe. 2025. Knowledge, perception, and practices of wildlife conservation and biodiversity management in Bangladesh. Animals 15(3): 296.