We live in a time when wildfires, floods, pollution, and degraded habitats are part of our daily reality. This reality significantly affects every species around us. The dominant view in global biodiversity science is that species are now disappearing at rates 100 to 1,000 times higher than natural background extinction rates. Given this pace, we are currently experiencing the early stages of the sixth mass extinction, driven by human activity.

In Vanishing Life on Earth, Professor Bimalendu B. Nath—science communicator and scientist with expertise in genetics and evolutionary biology—walks readers through Earth’s evolutionary history and highlights the intricate interdependence of species that has developed over millions of years. Placing the species we’ve lost in the context of their evolution over epochs emphasises that they aren’t just names in a museum catalogue. Instead, they are ancient lineages with unique geological, ecological, and historical significance.

Nath encourages readers to learn and reflect, prompting vital questions such as: why does biodiversity loss matter? What lessons have we learnt from the past? His holistic approach linking evolutionary biology with conservation policy adds depth often missing from popular science books. I look at it as the E-E-P trinity—integrating evolution, ecology, and policy to support the global “One Health” goal, which views human, animal, and environmental health as interconnected. Throughout the book, Nath also poses a question directly to the reader: what can we do to prevent more loss?

This book is especially suited for young readers, including high school students and undergraduates. It could also be a valuable science literacy resource for educators, journalists, conservationists, and non-specialist professionals in the sustainability or policy space.

Making science accessible

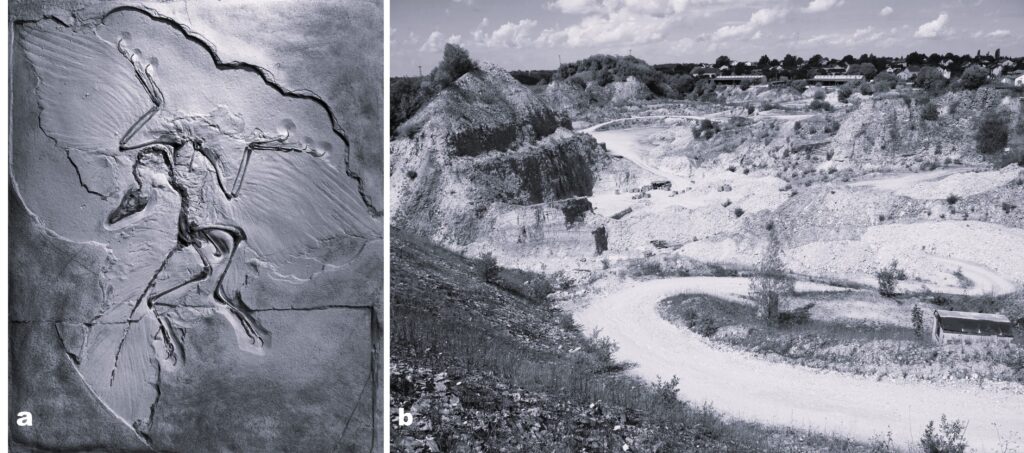

What sets Vanishing Life on Earth apart is Nath’s ability to balance science and storytelling—translating complex scientific ideas into accessible language. His infographics, fossil snapshots, and timelines enhance the reading experience, providing visual anchors that allow readers to trace evolutionary and extinction events more clearly.

He begins with Earth’s earliest stages, long before life appeared, and guides the reader through the debates over whether life first sparked on land or in the sea. From there, Nath details the branching of species (or the diversification of life) and how geological calendars and fossil records act as evolutionary clocks to help us understand deep time.

For readers new to the subject, the book provides a foundational overview of major evolutionary events, from continental drift to past mass extinctions, explaining how natural forces such as volcanic eruptions, global cooling, and ice ages shaped species’ survival. Nath draws on popular culture references such as Ice Age and Jurassic World to make scientific concepts relatable. To underscore that evolution is not optional but essential for survival, he offers a playful analogy for natural selection: “Imagine a game of musical chairs, where nature controls the pace of the music!”

Geopolitical linkages

One of the book’s standout features is how it connects Earth’s natural history with geopolitical developments through case studies. This method offers a multidimensional perspective on how human actions—from colonial expansion and global trade to modern warfare—have reshaped ecosystems and contributed to biodiversity loss. For instance, the brown tree snake, an invasive species introduced to Guam following World War II, caused the extinction of several native bird species. Similarly, the cane toad in Australia, introduced initially to control agricultural pests, became a threat to native species instead.

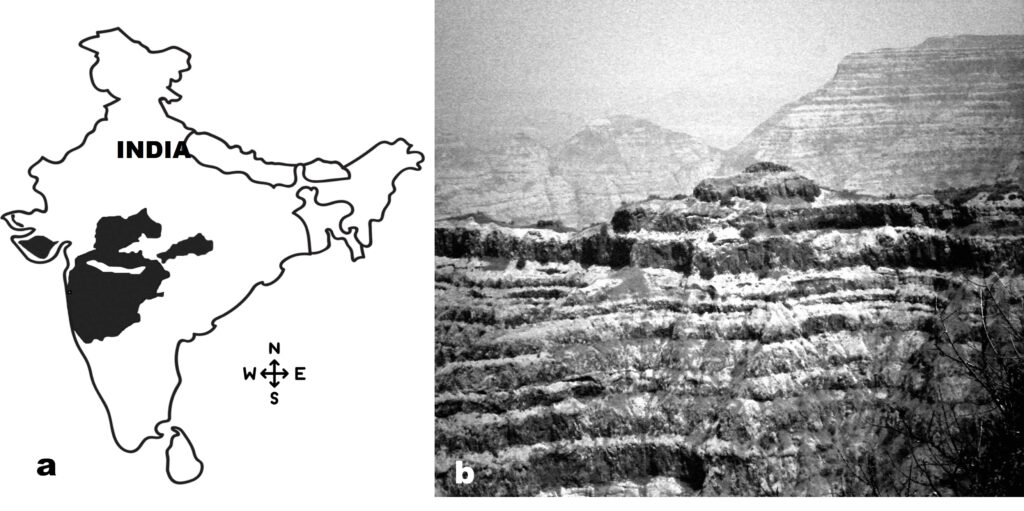

The book excels at making complex topics such as the “Big Five” mass extinctions understandable to a general audience. Consider one of the most well-known cases: the dinosaur extinction. Rather than present the event with a single-cause explanation, Nath highlights evidence that points to a combination of factors, such as the massive Deccan Traps volcanic eruptions in western India and the Chicxulub asteroid impact, when a roughly 10-kilometre-wide asteroid struck Earth in what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

From mammoths to mynas, Nath chronicles the extinctions that coincided with the spread of modern Homo sapiens, including the dodo, passenger pigeon, Tasmanian tiger, woolly mammoth, Irish elk, and Japanese otter. More recent examples like the lionfish invasion in the Atlantic or the ecological disruptions caused by mynas in Hawaii reinforce a recurring theme: human interference, both deliberate and accidental, can irreversibly alter ecosystems.

Real-world relevance

The book reminds us that while Earth’s history spans 4.5 billion years, modern humans have only existed for about 200,000 years. Yet in this brief window, our activities have drastically altered the planet through deforestation, pollution, overconsumption of natural resources, and habitat destruction. Drawing from recent findings, such as estimates that over a million species are now at risk of disappearing forever, Nath highlights that extinction is not just a scientific issue anymore—it is a societal one. Despite the current challenges, this book builds hope through conservation success stories such as the recovery of the bald eagle, green sea turtle, and giant panda. These examples show meaningful change is possible when scientists, policymakers, and communities work together.

While Vanishing Life on Earth offers a well-rounded perspective on the topic, a few subtle additions could have enriched its depth. A short discussion on molecular and genetic tools used in assessing and protecting endangered species would have introduced another layer of interesting scientific relevance. Likewise, regional case studies—such as biodiversity hotspots like the Western Ghats or community-led conservation involving Indigenous knowledge in protected areas or Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs)—could have offered local context and models of biodiversity stewardship. These omissions, however, may be an intentional choice to keep the book accessible and broadly focused. Within its chosen scope, the book succeeds in delivering a timely and impactful message.

Overall, in an age of ecological amnesia, where each generation accepts a more degraded environment as normal, this book fosters not only ecological awareness but also emotional and ethical intelligence. These qualities, taken together, feel essential for reshaping our relationship with the natural world.

As the renowned evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky once wrote,“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” Nath’s book reminds us that this truth still holds—perhaps now more urgently than ever.

Further Reading

Gadagkar, R. 1997. Survival Strategies: Cooperation and Conflict in Animal Societies. Harvard University Press.

Kolbert, E. 2014. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt and Company.