Feature image: The Balaton Highlands, Hungary, at dawn

Environmental change is occurring on a larger scale than ever, seriously affecting the planet, as well as our society. This includes droughts, floods, loss of natural habitats, and pollinator declines, just to name a few on land. These global changes are becoming increasingly more severe and occurring faster than ever. And while understanding the present is not easy, predicting the future is a bigger challenge.

Developing realistic scenarios is one way to plan for an uncertain future, while another is to dramatically increase our flexibility and adaptive capability. Complex challenges, such as climate change, call for the integration of knowledge from actors across different backgrounds. From farmers to decision-makers and from scientists to artists, everyone can play a role in shaping a more sustainable future. And a diversity of ideas and experience is a good start for pre-adaptation: preparing ourselves (our families, our society) for the future—whatever it may bring.

This article shares our findings from one such strategic planning exercise, carried out in the Balaton Highlands of Hungary. The highlands—located on the northern side of Lake Balaton, Europe’s largest shallow lake—are a mosaic of forests, meadows, vineyards, agricultural areas, and small human settlements (where tourism, focusing on wine and recreation, is becoming increasingly important). The future of the landscape and its people will be heavily impacted by climate change. Temperature and precipitation directly determine which grape varieties (white in the present but maybe blue in the future?) or fruit cultivars (almond in the present but maybe fig in the future?) will be dominant, and which new species might invade or can be introduced. Dozens of olive trees, if not yet plantations, already enrich the view on this landscape.

Farmers, ecologists, designers and other stakeholders are increasingly involved in landscape futuring—experience-based speculations on the future that are grounded in science and illustrated with art installations. For this, multi-disciplinary thinking is crucial: ecologically sound, sustainable solutions cannot be realised until they are proven to be economically feasible and accepted by various actors in a cultural sense. Our exercise, therefore, included a literature survey, interviews with different stakeholders, highly interactive discussions with students, and a living lab experience. The latter involved inviting various local actors to participate in an open innovation ecosystem that integrated research and innovation through co-creation in a real-world environment (rather than an isolated lab).

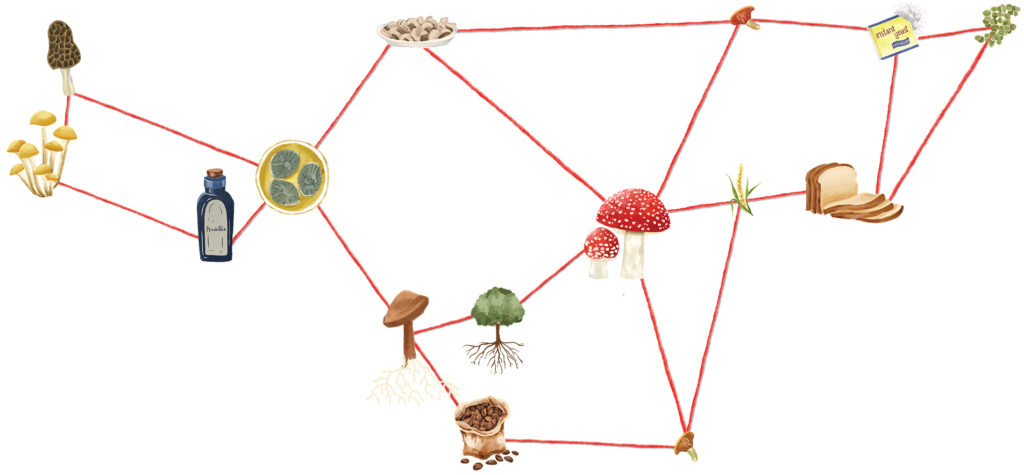

We applied a special emphasis on education: if we are talking about future generations, it is only fair, logical, and useful to involve them. Based on earlier interviews with local farmers (as well as interviews with farmers in an Italian olive plantation), we identified the most critical issues and challenges related to the local effects of global change. During a week-long course, students and instructors worked together on three subtopics that had been identified earlier, focussing on visual, audio and food-related layers of the landscape. For example, we prepared food using only edible wild plants available in the area, including traditionally foraged wild plants (such as dog rose, Rosa canina). A closing workshop helped to discuss the preliminary outcome with a diverse group of players.

At the end of the week, students and instructors shared their results in a combined, immersive future landscape in three parts: a video and soundscape and foodscape installations. This exhibition was then offered as a provocation and used as an engagement tool for inviting local stakeholders to debate and discuss possible ecological futures. The landscape installation thus created a space for collaboration between ecologists, designers, artists, and local stakeholders to share knowledge and think together about the changing climate in the Balaton Highlands, and to explore possible actions towards pre-adaptation, preparing ourselves for a possibly risky future. This working methodology adhered to a critical (and speculative) design approach, wherein the artwork produced served as an embodied critique or commentary—specifically concerning issues of land use and climate change in this instance.

We were interested in how our mindsets changed after this immersive experience. One key finding was that economic considerations are unavoidable in landscape futuring, as real estate prices may exclude most local farmers from owning a piece of land. We concluded that mixed-crop agriculture (such as grape and olive) seems to be the best solution for dealing with climate-related uncertainty. We also noticed huge differences among farmers (and small, local communities) in terms of openness and flexibility. This experience helped participants think strategically, therefore helping with pre-adaptation for the future, and also making them engines of societal change.