(This is a fictitious account of an Irula snake catcher, based on the real-life award-winning Irulas, Vadivel Gopal and Masi Sadaiyan.)

I felt a sense of pride and joy as I sat in front of the TV and watched my Irula brothers and mentors, Vadivel Gopal and Masi Sadaiyan, receive the prestigious Padma Shri award— one of the highest civilian awards of the Republic of India. The hard work they had put in all these years was finally being recognised. I felt that I, too, had received an award that morning, because I am also from the Irula community, and our forte is catching snakes.

Our ancestors have passed down this unique skill to us and now it has become our livelihood. But what people don’t know about us is that we are also expert foragers of herbal medicines and know the forests like the back of our hands. Getting this award is not only a huge experience for Vadivel and Masi but for our entire community, as well.

It hasn’t always been ‘smooth scaling’ for us, pardon the pun. When the Wildlife Protection Act was introduced in 1972, there was a ban on selling snake skins and we found it hard to maintain our livelihood. Then we got a new lease on life when, with the help of a senior herpetologist (a person who studies reptiles and amphibians) and conservationist Rom Whitaker, we founded the Irula Snake Catchers’ Industrial Cooperative Society. Our talent was recognised and put to good use, to help both humans and snakes. It was now official—we were licensed professional snake catchers and venom extractors.

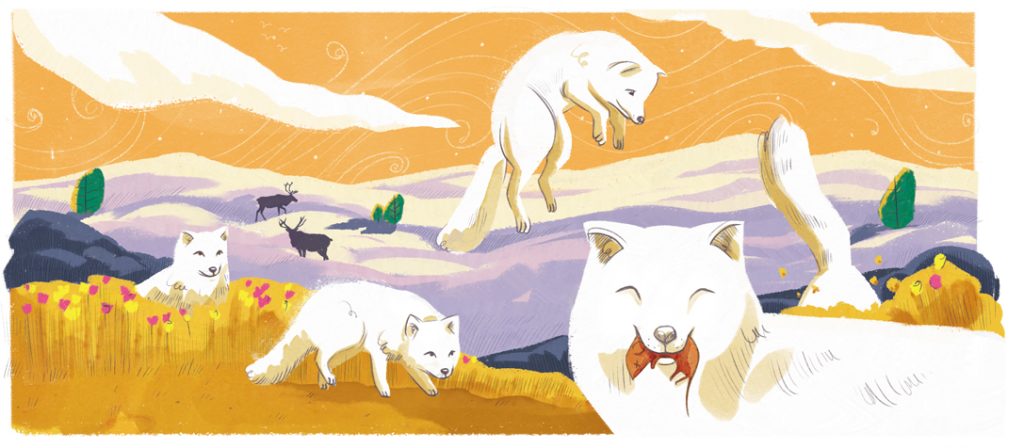

The Irulas were soon recognised as skilled snake catchers and were wanted internationally for snake catching missions. I had the privilege of accompanying Masi and Vadivel on one of these memorable trips. This was our mission to the US, where we were recruited to catch Burmese pythons, which are considered a threat in Florida as they are an invasive species.

Going abroad to a strange new country where customs are totally different from ours was overwhelming. Being on board an aeroplane was very exciting since I had never flown or stepped outside my country. The huge skyscrapers of Florida towered over me. Amidst the hustle and bustle of the cityscape, I could always feel the cool sea breeze threading its way through, taking me back to good old Chennai.

The Americans found our methods of catching the pythons a little unorthodox. I understand that, to inexperienced people, covering yourself with snake poop is not a very common technique. But my rather experienced friends told them, ‘You cannot catch a snake if you are not covered in it’. In other words, to catch a snake, you have to be the snake. During our trip, we caught many pythons, but none were as phenomenal as the 16-foot-long female python we caught on our second day. Fun fact, the average adult Burmese python is at least 7 feet long, and goes all the way up to 19 feet in length!

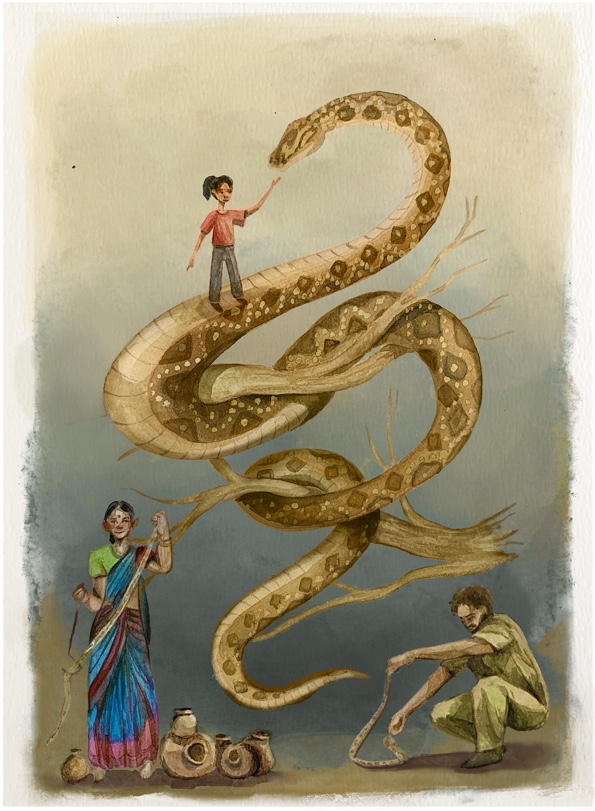

At home near Chennai, we not only track and catch the snakes but also extract their venom. In India, we have four snakes that we are allowed to target for this purpose: Indian cobra, common krait, and saw scaled and Russell’s vipers. We take the venom out of the snake so that the snake is not harmed at all. We do this only in certain seasons, rather than year-round.

You might imagine a complicated process, but it’s pretty simple. We start by catching the snakes and keeping them cool in clay pots. When they are taken out, the snakes open their mouths with fangs, ready to lunge. We keep a container wrapped in a plastic film ready. The fangs go straight through the film and the snake releases the venom into the collection vessel. We mark each snake so we can recognise it in the future, which ensures we do not extract venom from each animal more than three times. After the venom is extracted, the snakes are then released into the wild, to go about their lives, and the collected venom is sent to anti-venom companies. Our Snake Catchers Society has a lot of ‘hiss’tory with them (in a good way of course)!

The most rewarding experience is showing our work with snakes to children. These young, fresh minds find our methods and everyday work fascinating. I look at their faces watching us: some are filled with awe, while some are (understandably) drawing back in fear. Snakes don’t mean to do any harm. In India, these reptiles feed on pests such as rats and insects that would otherwise have a field day with the farmers’ crops. Hence, we consider cobras a friendly species—‘nalla pambu’, which literally translates to ‘good snake’ in Tamil. I believe that it is vital that we teach children not to fear snakes and, instead, to appreciate nature and to bust myths and spread awareness about these mostly misunderstood reptiles.

Masi and Vadivel’s big win is an even bigger contribution to the Irula community. I think that getting a prestigious award incentivises youngsters like me in our community to use the skills our ancestors have (very carefully) passed down to us. I hope we are a part of the bigger picture—helping humans to bond with their fanged friends!