It is the year 1830, and the scientific atmosphere in England is charged. Charles Lyell, a geologist whose work later influenced the young and impressionable Charles Darwin, is making waves in the scientific community. Lyell had just proposed a bold theory of species extinction via gradual changes in the landscape across millions of years. It defied the long-standing theory of extinction by sudden catastrophic events, as put forth by Georges Cuvier.

However, Lyell also mocked the idea of a fixed direction in the history of life, as propounded by Cuvier. He reckoned that the sequence of mammals arriving before reptiles and amphibians is not set in stone, contrary to what fossil records suggest. Extinct reptiles such as Ichthyosaurus can, under suitable conditions, reappear to reclaim the seas. In a hilarious rebuttal, Henry De La Beche, a fellow geologist, drew a comic titled “Awful Changes” starring a reappeared Ichythyosaurus donning a pair of spectacles and giving lessons to fellow Icthyosaurs on the extinct Homo sapiens:

“You will at once perceive that the skull before us belonged to some of the lower order of animals; the teeth are very insignificant, the power of the jaws trifling, and altogether it seems wonderful how the creature could have procured food.”

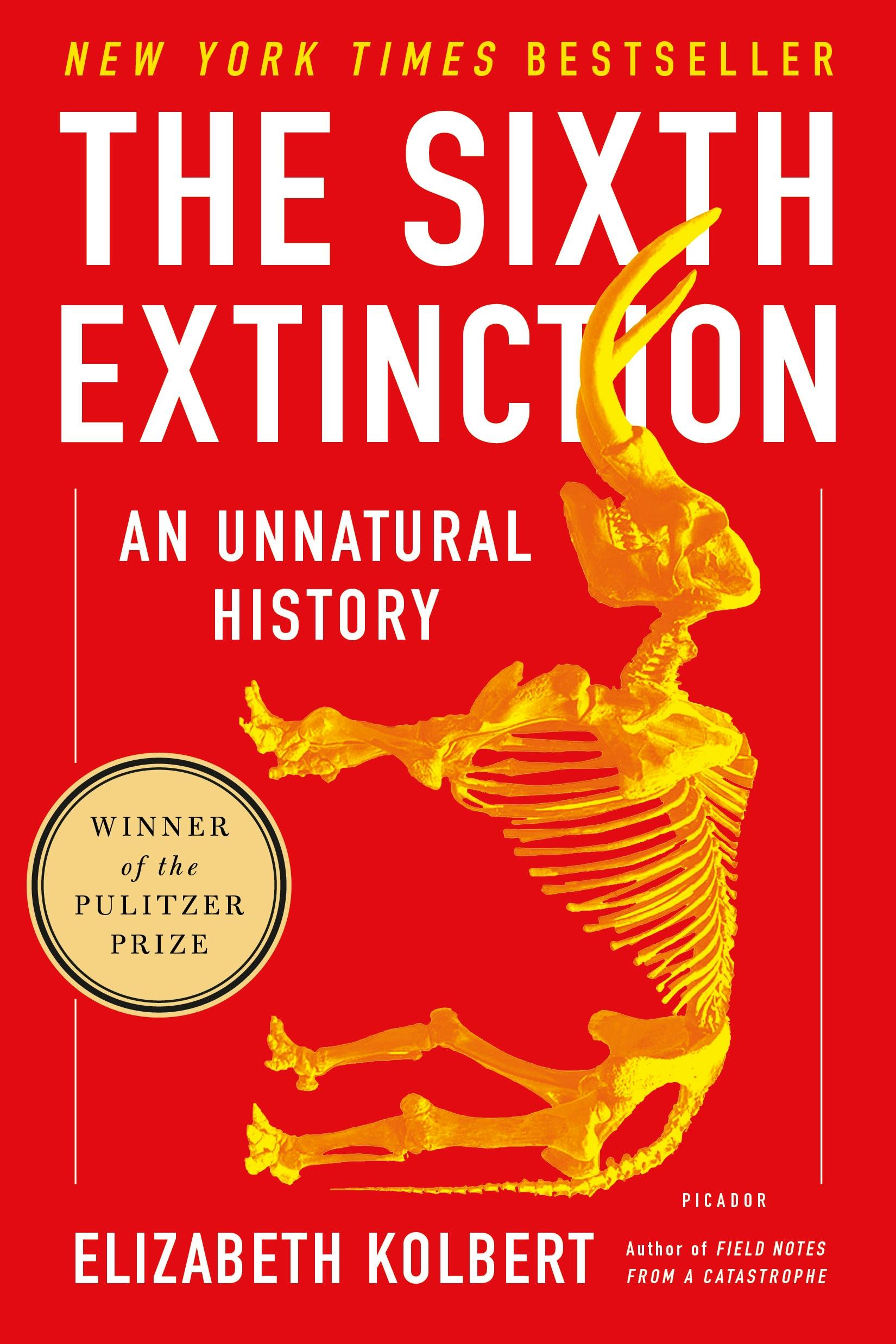

It is not just a dig at humans or the concept of resurrecting species but also at Charles Lyell and his nearsightedness. Such tussles in the scientific world serve as occasional subplots in The Sixth Extinction written by Elizabeth Kolbert and published by Henry Holt and Company in 2014. Kolbert uses these tidbits of history as a springboard to the main plot of the book, which concerns contemporary human-driven extinctions due to global warming, ocean acidification, habitat fragmentation and invasive species.

Kolbert begins each chapter by transporting us to a place and a time, be it on top of a ridge in the present-day Peruvian Andes or off the coast of Iceland in the 1800s. She describes the tell-tale signs of our influence on the landscape and its biodiversity through her own observations and conversations with scientists. Every chapter also features a species on the brink of extinction or already lost from our world.

Starting with scores of frogs mysteriously dropping dead across the Americas and Australasia, Kolbert traces their downfall and that of other species to a few culprits across 12 of the book’s 13 chapters. She scrutinises each culprit’s fingerprint in the present and past eras. During one of her many explorations, we learn that the oceans we are swimming in today are nearly 30 percent more acidic than they were during pre-industrial times. Global temperatures are around two degrees higher than they were two centuries ago. However, the clincher is that these levels are no strangers to our planet.

Many pages of life on Earth are filled with gorier periods of global warming, ocean acidification and ecosystem collapses. So, what is the difference between the past and the current extinctions? Does it matter if humans or a giant asteroid are to blame? Don’t the consequences remain the same?

This book provides some clarity to these questions. Kolbert masterfully draws parallels between the extinctions of the past and what we are witnessing today. She eases even the most novice of her readers to complicated subjects by starting with something familiar and slowly building her way to the unfamiliar. Her liberal use of analogies allows us to navigate through complex concepts seamlessly. In one such instance, she uses a construction analogy to describe how carbonate ions needed to build coral reefs—in the form of calcium carbonate—are increasingly sequestered as carbonic acid in our relatively acidic oceans: “Imagine trying to build a house while someone keeps stealing your bricks.” Such analogies make for a light read, even for people who find science daunting.

Aside from the writing style, the content itself is diverse and global. However, as a South Asian, I would have liked to see reportage from the Indian subcontinent. Its absence reflects the dearth of datasets and field studies in the region despite having some of the world’s richest assemblage of flora and fauna. Nonetheless, Kolbert manages to underscore the global scale of the issues without mentioning South Asia. Further on, while discussing the extinction of large mammals such as mammoths, she describes how these extinctions coincided with the transcontinental spread of our species. She cursorily mentions an alternative theory of fluctuating climate without delving into the supporting evidence for the same. However, we have proof of recent ice ages restricting the ranges of these large mammals, with humans administering the final blow.

Despite a few shortcomings, Kolbert keeps her readers hooked throughout the book as if she is writing a thrilling murder mystery. However, unlike the macabre atmosphere of such novels, she adopts a matter-of-fact tone with some glints of drama and, surprisingly, humour for a rather grim subject. Her conversations with scientists are the only time we sense a tone switch. She alludes to the emotional turmoil researchers often experience when witnessing the large-scale demise of their beloved group of species. On the approaching extinction of coral reefs, she quotes J. E. N. Veron, a former scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science:

“A few decades ago, I, myself, would have thought it ridiculous to imagine that reefs might have a limited lifespan. Yet here I am today, humbled to have spent the most productive scientific years of my life around the rich wonders of the underwater world, and utterly convinced that they will not be there for our children’s children to enjoy.”

You will appreciate Veron’s sentiments better after reading Kolbert’s beautiful take on coral reefs. Her comparison of coral reef ecosystems to “underwater rainforests” in the middle of a “marine Sahara”—followed by her justification for this imagery—evokes a sense of sadness at the thought that these ecosystems may not be around for long.

What stood out for me are a few occasions where Kolbert contemplates her place in the larger scheme of life. One such golden nugget is while she is collecting water samples at night in the Great Barrier Reef. All around her is darkness stretching from horizon to horizon; all she can see are the mighty stars above her. “The reason I’d come to the Great Barrier Reef was to write about the scale of human influence. And yet Schneider and I seemed very, very small in the unbroken dark.”

Another moment is amongst army ants in the Amazon. She felt one needed to “paint oneself into a corner” to witness army ants in their millions, marching through the forest floor and ravaging anything along the way—including you if you panicked! Her description of our current era, reduced to a sediment layer no thicker than a “cigarette paper” in an unimaginably distant future, knocks out any lingering egocentric tendencies of a haughty reader.

You will soon realise that this book is not just about mighty army ants, dying frogs or breathtaking coral reefs. It is about all the rabbit holes of patterns that lost species of the past, present and future have fallen into, leading to their inevitable demise. It is about how extinction is a normal, slow-paced process, but also how the rates on a few rare occasions have shot sky high and brought life on Earth down to its knees. It is about the story of generations of scientists before us and their struggle to accept the concept of extinction, something Kolbert notes that even three-year-olds take for granted today as they play with their dinosaur figures. It is also about the extraordinary effort mankind has embarked on to save what is left, the tremendous irony of which you will appreciate after reading this book.

While we are almost sure that the extinct Ichthyosaurus will not reappear, Jan Zalasiewicz, an expert on extinct graptolites, predicts that giant rats will take over the world when the dust settles and the sixth extinction runs its course. He reckons a species or two may start “living in caves” and “wearing skins of other mammals” they kill to cover their nakedness. Henry De La Beche might have been more accurate if he had sketched Prof. Rattus magnum instead of Prof. Ichthyosaurus.