The moon rises above the jagged mountains, casting a soft, pale light on clusters of towering agave stalks and their branches full of flowers. A gentle breeze sways the flowers and the pungent odour of the sweet nectar wafts towards us as we sit, silent and waiting, by the agave. We hear a soft whoosh by our heads. Suddenly our infrared camera screen comes alive with frantic activity as a group of seven small, brown bats flit up to the flowers in rapid-fire succession. A split second is all each bat needs to lap up the sugary nectar that fuels their nightly foraging bouts. They continue their aerial feeding dance for several minutes, until they decide it’s time to move on to the next agave patch. They will continue this pattern throughout the night, taking periodic rests among rock outcrops or their roosting caves, where they groom, socialize, and rest.

These hungry bats are endangered Mexican long-nosed bats (Leptonycteris nivalis). Undertaking a spectacular 1200-km annual migration, pregnant females leave the mating cave in central Mexico to seek out a handful of maternity caves in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States, to give birth to their single pup. Males stay behind in bachelor colonies.

Mexican long-nosed bats, along with their close relative the Lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae), feed on the energy-rich nectar from agave plants in the desert and mountain ecosystems they call home. Not quite as graceful or able to hover as hummingbirds, they get covered in yellow pollen

during their rhythmic feeding bouts. They move among agave patches throughout the night, spreading this pollen near and far. Able to carry and disperse pollen over 50 km in a night—much farther than most birds or insects—these bats are critical to connecting agave populations, helping maintain their genetic diversity and ultimately increasing resilience to threats, such as pest and disease outbreaks. However, these nectar-feeding bats aren’t the only players that have a close relationship with agaves. Another

key player? People.

Agaves and people

The next afternoon as the bats are tucked away in their cave, I take a walk with Armando, a Mexican farmer whose family lives in a communal ejido in the mountains of Nuevo León. We stroll through his parcela, the agricultural plot where he and his family grow corn, beans, and other crops. He stops along the fence line at a two-metre-tall agave with a large hole carved from the centre. Bending over, he scoops a cupful of cloudy liquid from the hole: agua miel, or “honey water”, the sap of the plant. I taste the liquid: it’s sweet but with a very plant-like taste. “Agaves are the sustenance of the ranch,” he says.

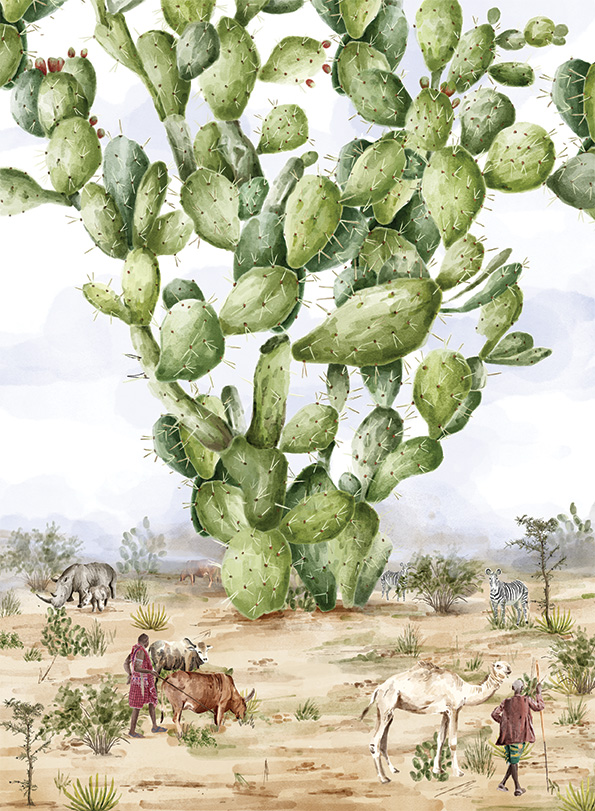

Like Armando, many rural ejidatarios (farmers) across Mexico harvest and use agave plants to obtain traditional beverages like agua miel and pulque (fermented agua miel); to distil liquors like tequila and mezcal for sale in local, regional, or even international markets; to feed to livestock, especially in times of drought; to serve as “living fences” that keep livestock out of crops or to delineate property boundaries; to retain soil and prevent erosion on hillslopes and along roadsides. Agaves sustain their livelihoods, allowing them to retain their homes and ties to the land even when other livelihood sources, such as livestock and farming, let them down. With increasing periods and severity of droughts and increasing desertification in Mexico, drought-tolerant agaves offer a lifeline for many families.

Armando points down to the base of the agave at several small baby agaves, called hijos, growing from the mother plant. These hijos are clones, underground offshoots that are genetically identical to the mother plant. Like their mother, they too will eventually shoot up a massive flowering stalk and offer nectar to bats and other animals. Clonal reproduction offers a safeguard to the mother plant in the event that seed production through pollination is not successful. For many agave species, sexual reproduction through seeds helps maintain genetic diversity, while clonal reproduction can help maintain population numbers.

In fact, Armando explains that for many agave species, proper “castration” of the mother plant—hollowing out the centre of the plant to create the hole where the agua miel collects—stimulates production of clonal hijos. This provides the harvester with new baby plants that they can then transplant as living fences or for future harvest. Thus, harvest of agaves, combined with sustainable ranching practices, can be an important way to safeguard agave populations for future use by people.

The importance of agaves for bat migration

When agaves are left to flower, they provide an important food source to nectar bats and are pollinated in turn, thus completing the cycle that benefits bats, agaves, and people. Rural communities throughout Mexico, as well as private and government lands in the U.S., are important stepping stones along the bats’ migratory route, connecting critical roosting caves with a path of foraging resources.

Back at the agave we had monitored the night before, the vibrant yellow flowers are beginning to shrivel in the sun and heat. As agave flowers shrivel across the landscape, the bats move along on their migration. Flower death does not, however, signal the end of the agave’s life cycle. The pollinated flowers soon become ovular fruits, with hundreds of tiny black seeds nestled inside. These fertilized seeds give the plant an opportunity to pass on its legacy in the form of new seedlings, if they successfully germinate.

Native to deserts and semi-arid habitats and with over 250 species worldwide, agaves have been part of cultural landscapes for over 10,000 years. However, agave populations and the habitats where they occur are being lost to various threats, such as expansion of agriculture, unsustainable ranching, urban development, and climate change. Loss of agaves affects both the migratory bats and the people that rely on them. Efforts to restore agave habitat are being undertaken by organizations like Bat Conservation International. Through diverse partnerships with NGOs, state and federal agencies, industry partners, and local communities across the southwestern United States and Mexico, Bat Conservation International is promoting agave planting, sustainable agave use, and other land use practices that support both threatened bat populations and human livelihoods.

Naturally dispersed by wind and water, tiny agave seeds get a helping hand from Bat Conservation International’s partners. By propagating and nurturing the seeds into little seedlings for planting back in the wild, these agaves get a new chance to grow tall on the landscape and once again feed the bats and provide sustenance and livelihoods to people. Exclusion of restored areas from herbivores helps ensure the plants’ survival. Community training in sustainable agriculture and ranching practices helps ensure that communities can make a living from their land long into the future. Long-term community conservation agreements ensure that the agaves are protected until they flower and that restoration efforts are co-designed in ways that benefit the communities. Market-based initiatives like the Bat Friendly™ Tequila and Mezcal project, launched by Dr. Rodrigo Medellín of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and David Suro of the Tequila Interchange Project, work with liquor producers to certify agave farms that let five percent of their crop flower for pollinating bats.

These efforts to restore and protect a “nectar corridor” for migratory bats and communities require bi- national collaboration between Mexico and the U.S., bringing together people and linking ideas across a vast landscape. I think back to my walk earlier with Armando and recall a statement he made that couldn’t be truer or more motivational: “For us the agave is so noble that it gives us life.” Agaves do indeed give us life. But it’s not just us—agaves support a wealth of healthy ecosystems and wildlife species, some of them migratory. It is our responsibility to protect and restore agave habitats before it is too late and species like the Mexican long-nosed bat are lost forever.

Further Reading

Bat Conservation International. 2021. Agave restoration. https://www.batcon.org/our-work/protect-restore-landscapes/agave-restoration/. Accessed on October 5, 2021.

Bat Conservation International. 2020. Boosting bats by restoring Mexico’s agaves. https://www.batcon.org/article/boosting-bats-by-restoring-mexicos-agaves/. Accessed on October 5, 2021.

Bat Friendly Project. https://www.batfriendly.org/. Accessed on October 5, 2021