“Gajju! Come and see what I have found!”

Eight-year-old Gajju dropped the stick he held, making the other boys shout in irritation as their game of gilli danda, a rowdy game similar to cricket, came to an abrupt halt. He rushed off towards the sound of his grandmother’s voice. The village was peaceful in the early evening. The women were sitting beneath the shady trees, while the men napped inside the houses. When the oppressive heat of the desert afternoon faded to a pleasant warmth, they would return to their agricultural land. Gajju’s dadima was one of the oldest women in their village. It did not take Gajju long to spot her sitting beneath a dhak tree, known as the flame of the forest, holding a bundle in her arms.

“How slow you have become,” she scolded light-heartedly, but she smiled and shifted her foot to make room for the panting boy. “I have a task for you, Gajju.”

Gajju was intrigued. What could it possibly be? She unwrapped the bundle in her lap and gently pulled the shawl away to reveal a tiny, trembling baby gazelle.

Gajju was enchanted by the little gazelle. Dadima stroked its soft head gently with her thumb, and the gazelle gave a small bleat in response. “This is a chinkara, Gajju,” she said. “Your uncle found this little one lying beside her mother, who was dead—shot, perhaps, or maybe killed by one of the village dogs. He brought this fawn back and gave her to me to care for. I think it is time you helped raise a young gazelle, just like your father did when he was your age.” Grandmother smiled reminiscently. “Your father used to go everywhere with the little chinkara that he looked after. Even after becoming a full-grown adult, the chinkara used to visit him out in the fields and come to the village to eat in the summer months.”

“You mean I can keep this chinkara as a pet?” Gajju asked eagerly.

His grandmother shook her head. “Not as a pet, as a friend. Until she is old enough to go back to the wild.” She handed the trembling fawn to Gajju, who petted her gently until she stopped shaking and looked up at him with big, trusting eyes.

“This is the tradition of our Bishnoi clan,” said Grandmother, smiling. “We are the protectors of wild animals, especially the little ones who are helpless and cannot survive without protection.” She patted Gajju on the head. “You are finally being initiated into this ancient tradition, my child. Look after your little friend well.”

Days passed, and Gajju fell head over heels in love with the little chinkara, whom he had named Chutki. Chutki, too, adored the boy, trotting after him on shaky legs and curling up to sleep beside him every night. Gajju was sure to keep her inside the house after dark, for fear that a leopard, wolf, or jackal might try to snatch Chutki if she was left outside. The little chinkara soon started responding to the love and care and became Gajju’s faithful shadow.

One day, Gajju woke up to find Chutki missing. Panicked, he rushed out of the small house shouting for her. But Chutki was nowhere to be found! Gajju knew in his heart that something must have happened to his little friend. He turned and fled towards the agricultural fields, where his father and uncle would be working. If anyone could help him find Chutki, it was his father.

“Babuji, babuji, come quickly!” Gajju cried upon seeing his father. His father was squatting on the ground, prodding at the soil. He looked over his shoulder and then sprang to his feet at the sight of Gajju’s terrified expression.

“What happened, son?” he asked, gripping the boy by the shoulders and looking into his eyes. “Are you well? Is everything ok with mai and dadima?”

“Something’s wrong with Chutki!” Gajju said tearfully. “She’s gone missing!”

His father scratched his chin. “Well, she couldn’t have wandered very far. She’s too young to travel long distances. We’ll find her. Don’t worry, Gajju.” He strode towards the edge of the field with his son trailing behind. “Let’s get one of the dogs to sniff her out.”

As his father went to find one of the village dogs, Gajju waited by the fence. He chewed on his fingernail, hoping that Chutki was all right. Suddenly, he heard a strange sneezing sound. Wait! Wasn’t that the call of a chinkara? The sneezing sound came again, faint but recognizable, and all at once Gajju knew it was Chutki calling to him. He took off in the direction of the sound, running as fast as his legs could carry him. “I’m coming, Chutki!” he panted aloud as he ran.

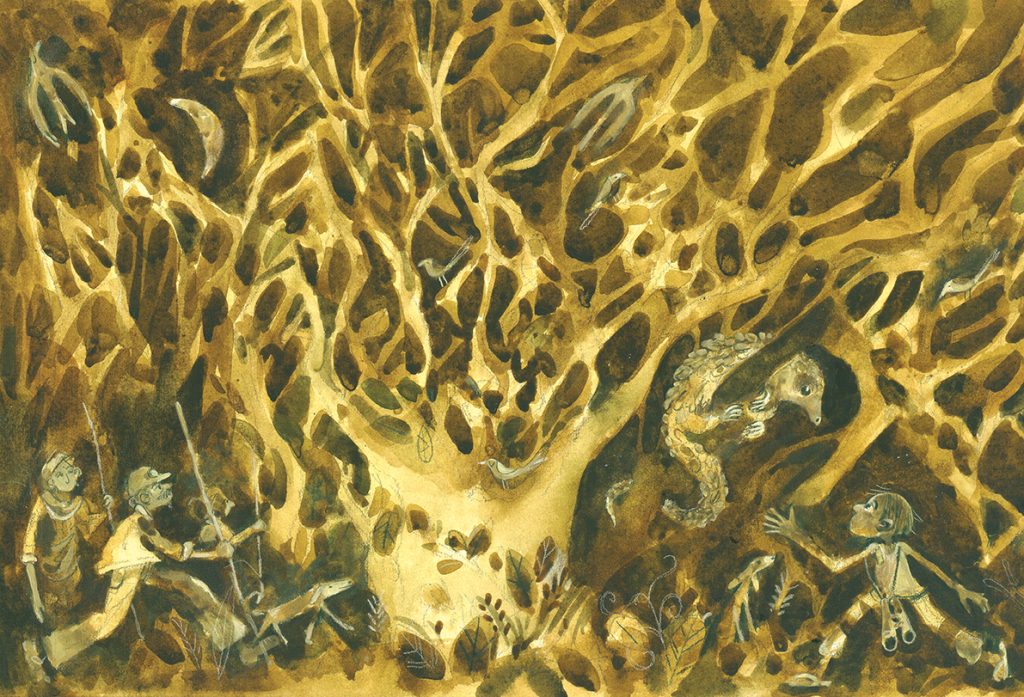

He skidded to a stop near a small clearing amidst clumps of mesquite or baavlia (Prosopis juliflora) trees. The thorns cut his arms as he pushed his way to the clearing, but Gajju hardly noticed, because in front of him was Chutki, her legs trembling and ears flopping, facing two hungry jackals.

The jackals glanced at Gajju and then focused on the chinkara once again, clearly dismissing the boy’s presence. Chutki huffed in fear, her eyes rolling. She looked exhausted, and Gajju felt anger welling up inside him.

“Go away!” he shouted, flapping his arms and taking a step towards the jackals. His father had always told him to appear big and confident when confronting a predator. “You can’t have her! She’s my friend, not your next meal!” The jackals retreated a step but one of them—the female—darted around Chutki, making the chinkara turn back to glance at her. The male snapped at Chutki from the front, and then leapt backwards as Gajju rushed towards him. Gajju was terrified of the jackals, but all he could think of was poor, frightened Chutki. He couldn’t stand by and watch the jackals attack her!

All at once, the cacophony of barking rent the air and two large village guard dogs burst into the clearing. Behind them came Gajju’s father, carrying a stout stick. At the sight of the dogs, the jackals fled into the thick brush. Gajju rushed to Chutki and dropped to his knees beside her, flinging his arms around her neck. “Oh, my poor Chutki, did they attack you?”

“Let me check her,” said his father kindly. He quickly examined the little chinkara, running his hands over her trembling body. “She’s fine, just terrified and probably in need of a good nap. Here, let me carry her back home.” He scooped up Chutki and beckoned to Gajju. The dogs joined them as they started back to the village.

“That was very brave of you, son,” said Gajju’s father as they walked along the dust path, the Prosopis trees forming a thorny barrier beside them. “Facing two jackals all by yourself is not an easy task for a little boy like you.”

Gajju shrugged. “I had to, Babuji. It was for Chutki. I couldn’t have left her alone to defend herself.” He shuddered. “I hate jackals. Those two would have killed her.”

His father half-smiled. “They’re carnivores, son. That’s what they do. Just as we are vegetarian, they eat flesh to survive. We cannot blame them for doing what nature intended them to do.”

“But they could have killed Chutki!”

“And now, we know that we need to keep a closer watch on her until she is fast enough to escape,” Babuji said calmly. “Don’t blame the jackals, son. Blame yourself for losing track of her. She is your responsibility.”

“I’ll never let her out of my sight again,” Gajju vowed fervently. “I’m sorry, Chutki. I let you down.”

Chutki opened one eye sleepily and huffed. Babuji smiled.

“I think she has forgiven you,” he said, as they arrived at the Bishnoi village. Gajju heaved a sigh of relief.

“I’m going to build Chutki a small pen when we get home, so that she will always be safe and not wander off,” said the little boy.

“And one day, when she is big and strong, we will let her return to the wild, as she was meant to be,” replied his father.