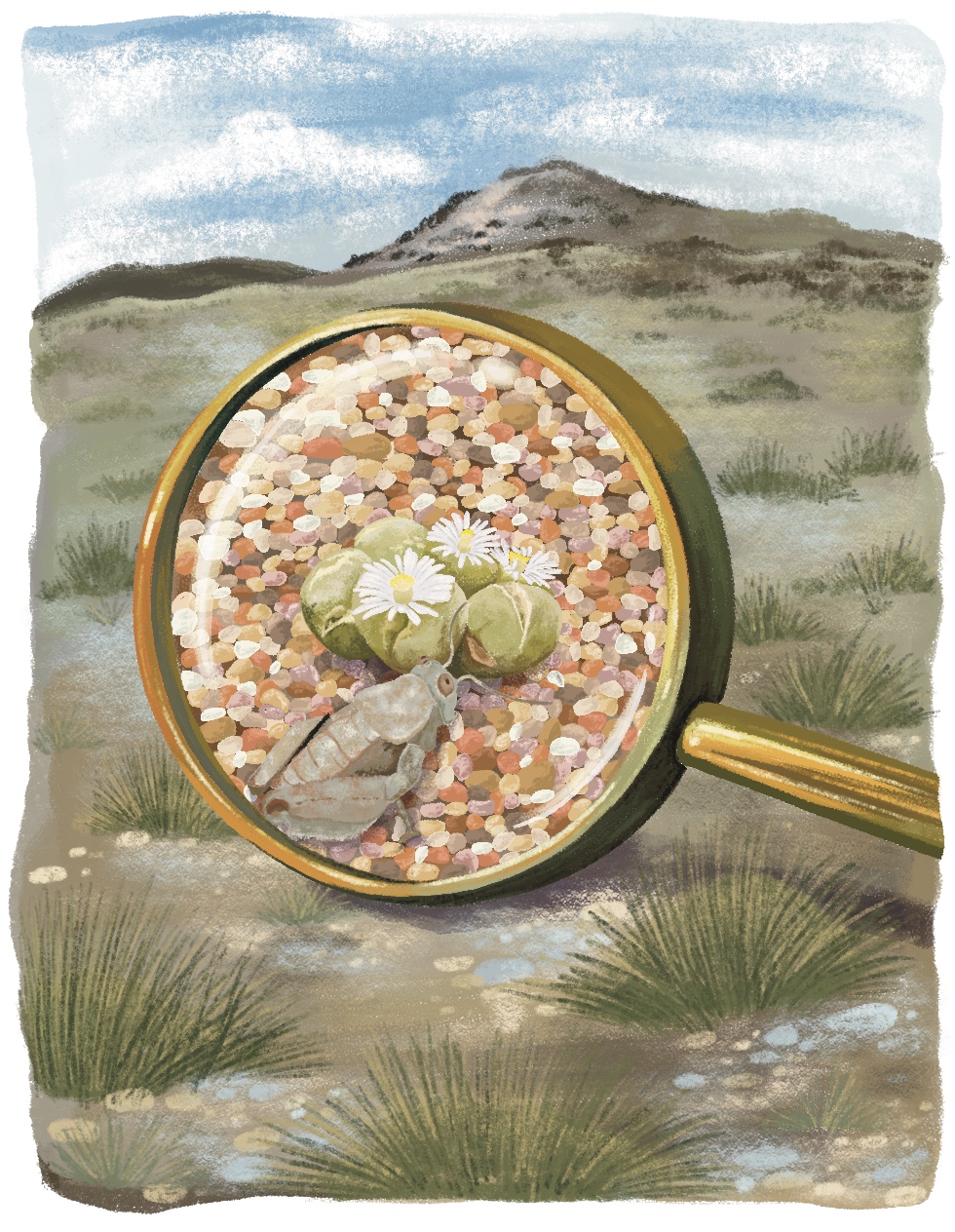

At first glance you’d think we were auditioning as extras for a zombie film, the way we were shuffling around, hunched over, staring at our feet. I will even admit to the occasional groan, as my back arched uncomfortably and the hot sun beat down on my neck. But we were not looking for succulent brains, rather for tiny succulent plants, almost invisible against the stony ground.

I was studying the diet of the Cape grey mongoose at a conservancy in southern Namibia, when a team of botanists from the National Botanical Research Unit of the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism arrived. Dr. Sonja Loots and her team were in the area to look for and count lithops, or living stones as they are sometimes known. True to their name, these small succulent plants look remarkably like stones, and finding them against the quartz-strewn outcrops they inhabit is a challenge. I had spent the last two months staring across the arid and seemingly barren landscape looking for isolated mongoose scats, so when they asked for help, I was more than happy to have a change of focus!

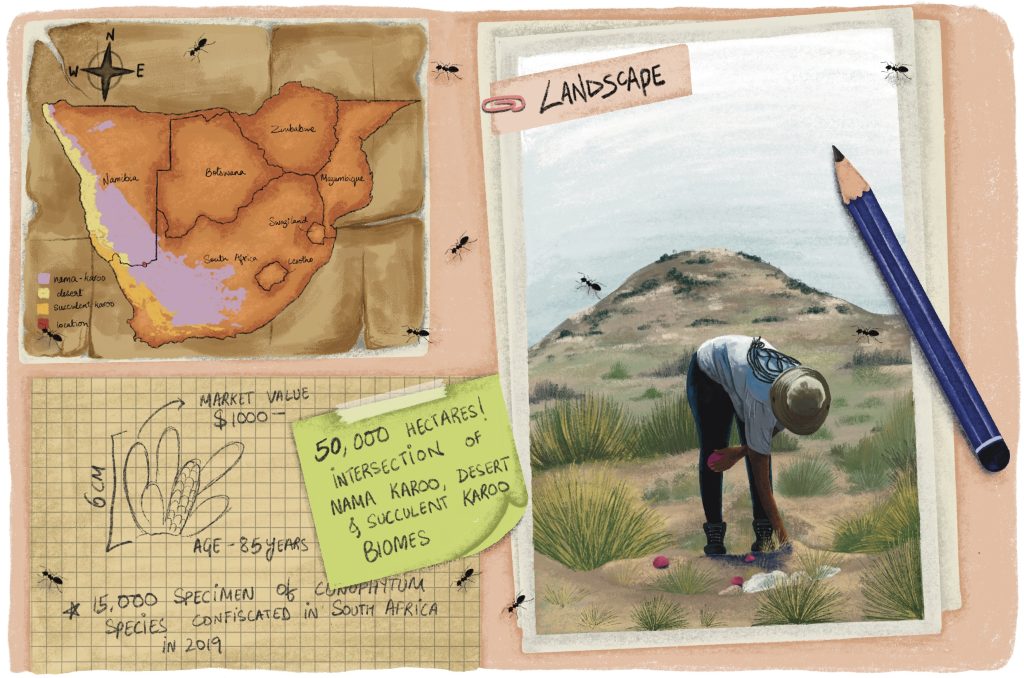

This region of southern Namibia is subject to extreme fluctuations in temperatures as well as low, unpredictable rainfall. Yet, its location at the intersection of three biomes — the Succulent Karoo, Nama Karoo, and Namib Desert —means that the area is incredibly biodiverse and home to many unique succulents.

These fleshy plants are well adapted to the arid landscape, with extensive shallow root systems that can quickly absorb the infrequent rain, and waxy leaves that can resist desiccation in the dry desert air. Many species are highly restricted in geographic range, with populations often found exclusively in areas measuring just metres across.

This was our first stumbling block. The core area of this conservancy is 50,000 hectares! Despite identifying several potential quartz grounds, it took over a day before we found a hill, or koppie, with a good density of the target species. On our second afternoon of preliminary searches, I found a delicate little plant, like a patch of feathers coming up out of the ground. Even my definitely-not-a-plant-expert eyes could tell it was not the lithops they were looking for, but equally it wasn’t anything we had previously seen. I called Sonja over, who after looking at it wondrously, said it was one of the rarer species of Avonia, and despite being barely 6 cm in diameter, this individual could be up to 85 years old and, thus, would be considered a collector’s item.

A growing threat in a vulnerable habitat

This was why we were out here in the hot desert sun. Elephant and rhino poaching get all the media attention, but succulent poaching in Southern Africa is a huge and growing problem. The popularity of these plants with collectors combined with the difficulty of propagating them outside of their preferred habitats, means that the poaching and illegal trade of the larger specimens and rarer species from the wild is big business. The scale of the problem is growing. In 2019, 15,000 specimens of a single Conophytum species were confiscated from poachers in South Africa. A large haul can have a street value of thousands of dollars. The plants themselves often do not survive translocation, and even if recovered, it is almost impossible to replant them without knowing exactly where they came from. For species restricted to such small areas, poachers can easily wipe out a population in just one day.

One of the major issues for these plants in Namibia is that very little is known about where they are found. This survey effort was part of a big push to get location data so that more areas can be protected. Only five percent of Nama Karoo in Namibia is in state protected reserves, with another 17 percent under some form of conservation management, making it the least protected biome in the country.

As we painstakingly searched each ‘pie slice’ of the circular survey area, we counted dozens of Conophytum and Avonia species, often clustered together in the less densely vegetated areas or sometimes snuggled against a larger piece of quartz. This area is currently under the conser- vancy’s protection, in addition to being difficult to access, which means that these populations are likely safe for now.

Historically, the greatest threat in this region has been overgrazing, with high stocking densities leading to land degradation and scrub encroachment. Up on the quartz koppies, where other vegetation is sparse, these succulents have escaped the worst of the damage. I pause to consider the life of my tiny plant — 85 years of drought and intermittent desert rain, growing slowly in this one spot in the middle of nowhere, surviving while all around it sheep and goats overgraze the arid grasslands until little more than dust remains.

Between the bare rocky ground and lack of charisma- tic megafauna that attract tourists and make other African biomes so famous, you’d be forgiven for thin- king the Nama Karoo was an empty, desolate place. However, that wasn’t always the case. In the past, this area was home to some of the largest springbok herds ever known, as they migrated from the summer rainfall regions of southwest Namibia to the winter rainfall regions on the South African coast. This phenomenon, known as the ‘trekbokken’, saw millions of springbok in enormous migratory herds that took days to pass by. Now those herds are small and scattered, and the land is divided up by fences enclosing farms with sheep, goats, and cattle. After years of drought in the area, many of those farms have since been abandoned, leaving behind an ecological vacuum.

New ways of seeing

There are large animals, such as oryx and brown hyenas, in the conservancy, but they are shy, and sigh- tings are few and far between. The largest species I had seen was the klipspringer, a small antelope. To be more precise, I saw the backsides of a group of klipspringers as they ran away from me! I had also spotted my study species, the Cape grey mongoose — which is very common and found almost everywhere in Southern Africa — only once.

Lacking the budget for a car, my mongoose project had been confined to a 10 km radius around the farmhouse. If I was really honest, things had started to feel ‘samey’ after two months. I walked the same transects each week, saw the same rubble-strewn mountains, the same common birds, rodents, and invertebrates. I do love these small things but, lacking the ‘wow factor’, perhaps it was the sort of dutiful love that you tend to take for granted. Sifting through endless grasshopper and beetle legs and drifts of four-striped mouse fur in mongoose scats, I felt like I wasn’t finding anything worthwhile, and began to question the value of my work.

However, the time I spent looking for lithops with Dr. Sonja and her team completely changed my perspective. Crouched down, staring at the quartz microcosm far below eye-level, I was suddenly struck by the sheer amount of life in the landscape. I saw at least three species of mantis stalking through the stunted grasses, grasshoppers of all shapes and sizes pinging between the stones, and toktokkies (various species of flightless beetles) tottering across the sand.

The creatures I saw living in this miniature ecoscape were the same things I had been routinely finding in my mongoose scats. They are present in suchnumbers thanks to the resilience of the tiny, specialist plants that underpin this habitat. They have managed to survive despite the numerous threats, thus preserving the diver- sity of this unique ecosystem. It will take time, but with the surrounding vegetation protected and allowed to recover, the invertebrates will creep back, followed by the birds and the small mammals, the larger herbivores, and the carnivores, until this whole corner of the Nama Karoo thrums with life again.

As the final afternoon drew to a close, we finished off the survey and I stopped to take in the subtle beauty of the terrain, which was glowing in the afternoon sun. It looks different to me now — a living landscape, where before it was just rocks. The following day, I resumed inspecting scat contents under the microscope with renewed enthusiasm, joyfully taking the remains of exoskeleton and fur as more evidence that life has clung on here against the odds. My project may be small, but it is still part of the vast and varied conservation effort to protect this unique habitat. I hope in the future that there will be more mongooses here, eating ever more abundant invertebrates and rodents of innumerable diversity. Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better or more valuable for conservation.

Further Reading

Fine Maron, D. 2022. These tiny succulents are under siege from international crime rings. National Geographic. www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/tiny-succulents-are-under-siege-from-international-crime-rings. Accessed on October 29, 2022.

Loots, S. 2019. Habitat characteristics, genetic diversity, and conservation concerns for the genus Lithops in Namibia. Doctoral thesis no. 2019:28, Faculty of landscape architecture, horticulture and crop production science. https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/16156/7/loots_s_190521.pdf. Accessed on October 29, 2022.

Lovegrove, B. G. and W. R. Siegfried. 1993. The living deserts of southern Africa. South Africa: Penguin Random House.