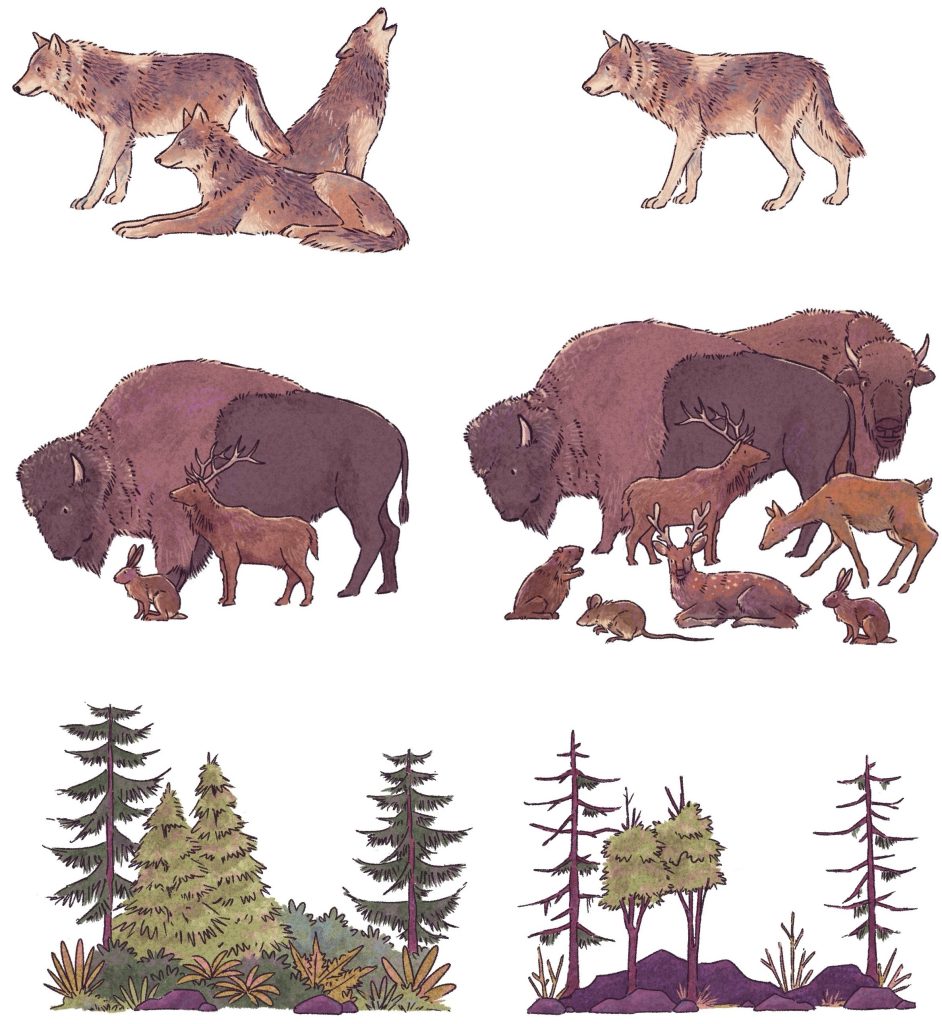

In an increasingly urbanised world, tensions between humans and large carnivores are mounting. Urbanisation exacerbates the issue of conflict between humans and large carnivores as our spaces begin to overlap and human-carnivore interactions become more frequent. These interactions can have negative outcomes on one or more of the interactants. Both parties are affected by urbanisation, with carnivores losing their habitat and potentially posing a threat to human lives, property and livelihood. As apex predators, large carnivores play a crucial role in keeping ecosystems balanced. A decrease in carnivore populations can lead to trophic cascades—predator removal alters the abundance among other trophic levels, such as prey and plants—impacting ecological services like regulation of disease, wildfire, and invasive species, carbon sequestration, and biogeochemical cycles.

Due to these serious implications, it is imperative to understand how these changes impact the evolution of both humans and large carnivores. Historically, the overlap in localities between humans and large carnivores has driven co-evolution between humans and certain species, and has even led to extinctions. With interactions increasing over time, humans have adapted through technological strategies, such as weapons, poisons, repellents, fences, and traps. Large carnivores, in turn, have been adversely impacted due to reduced species richness, diversity, population size, and gene flow. With overlap in shared space continuing to increase, it is critical to examine its effects on species’ evolutionary trajectories and mitigate the negative impacts that could lead to the extinction of biodiversity.

Historical impacts

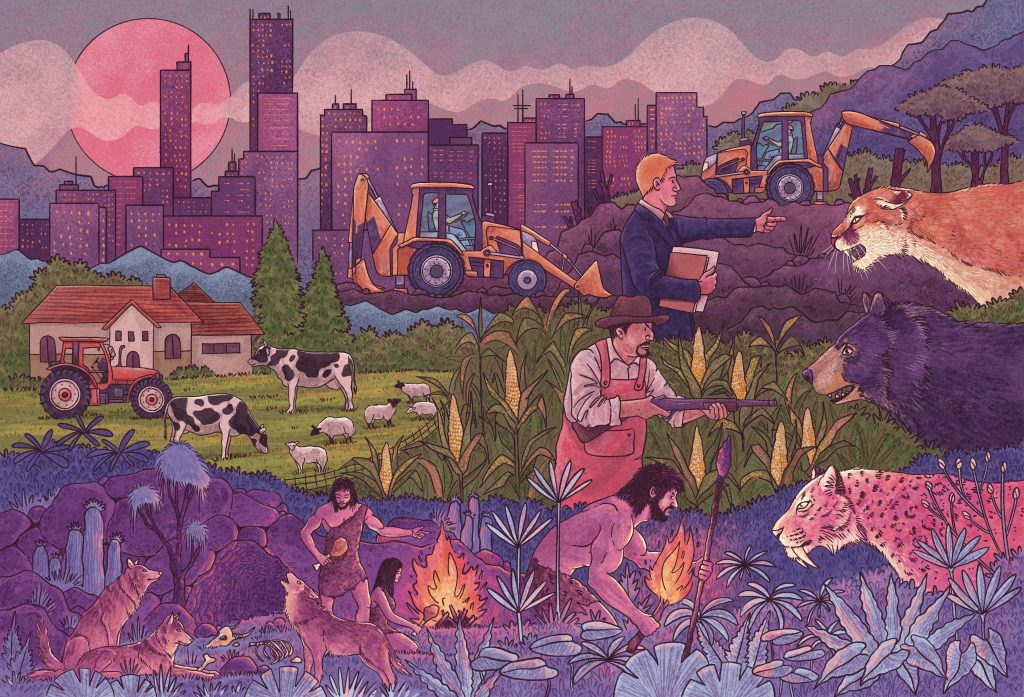

Humans and large carnivores have coexisted for over four million years. The competitive interactions between humans and large carnivores placed pressure on both parties, creating an opportunity for co-evolution. This created an ecological circumstance for humans to scavenge, while at the risk of predation. In fact, the pressure large carnivores put on humans likely influenced the shift towards cooperative defence, cooperative breeding, and changes in reproductive investment.

Early human co-evolution occurred specifically with hyenas, bears, and wolves that overlapped in localities, leading them to adapt to each other. Due to overlapping spaces, these carnivores likely interacted with early humans in various situations. Hyenas were able to exploit human-related feeding opportunities while providing a protective presence and ecosystem services by clearing carcasses, bones, and food scraps. Neanderthals are speculated to have explored hyena dens and exploited their bone and meat storage.

Similarly, bear dens were occasionally explored for materials and also used for shelter. At the same time, bears were noted to have utilised hominid remains as Neanderthal burial practices were typically held within their habitat. Thus, Neanderthals promoted a broader feeding niche for these scavenging species through their burial practices and provisioning of specific types of carcass scraps. Moreover, one of the most evident examples of co-evolution between early humans and carnivores is with wolves. Wolves and humans cooperatively hunted, and wolves provided services such as resource transportation and guarding. Over time, this commensal relationship led to the emergence of the domestic dog and hybrid pack-families composed of humans and dogs.

While early humans co-evolved with some carnivore species, fossil records indicate that they also negatively impacted the diversity of large carnivores such as early lions, sabre-toothed cats, and giant bear-dogs. Scavenging and kleptoparasitism initially drove their extinction, however, increased brain size, locomotor adaptations, and advanced tool use by humans further escalated the exploitation and reduction of the carnivore guild. Some of these factors contributed to co-evolution between humans and certain large carnivore species, such as hyenas, bears, and wolves. However, those that did not benefit from humans faced a greater risk of extinction. Simple tools and weapons created by humans put them on an even playing field with carnivores, but as technology improved, the balance fundamentally altered and shifted in favour of humans.

Modern impacts

In modern times, urbanisation is a key contributor to the imbalance between humans and large carnivores. Urban proximity can have effects on species richness and distribution. Previously, native species richness was negatively associated with urban intensity but not proximity.

However, urbanisation may not have the same effect on all species. Solitary species such as mountain lions were found to be less abundant with increasing proximity, while scavenging animals such as coyotes were found to be more abundant with proximity. Furthermore, a recent study found that while spatial avoidance did not occur in brown bears, their temporal behaviour did change. In human-dominated landscapes, brown bears have adapted by becoming more nocturnal.

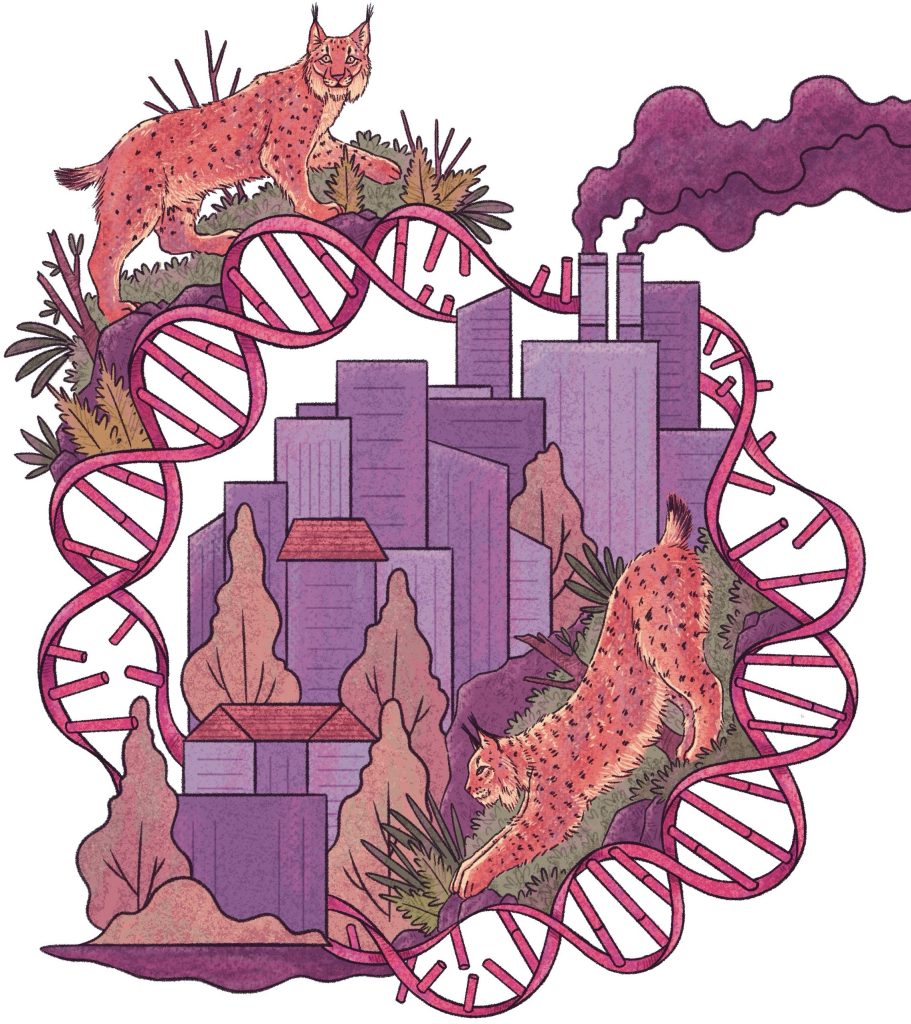

Besides the emergence of behavioural adaptations, urbanisation can also generate genetic changes within large carnivore populations. Habitat fragmentation caused by urbanisation disrupts habitat connectivity due to the emergence of human avoidance behaviours. In a study focused on bobcats, it was found that gene flow had decreased as a result of habitat fragmentation. In fact, the reduced gene flow was so significant that it resulted in two genetically different sub-populations of bobcats. As urbanisation becomes more prevalent, gene flow may continue to decrease leading to more sub-populations, inbreeding and overall less genetic diversity, culminating in higher risk of extinction.

Human-large carnivore co-evolution also affects species relations. In some cases, humans do not affect the occupancy of species, but the interactions amongst themselves. Changes in large carnivore populations have resulted in trophic cascading effects that extend to mesocarnivores, herbivores, and plants. This phenomenon, known as the human shield effect, argues that humans employ a top-down effect on apex predators, which in turn affects mesopredators and increases their spatial overlap. Mesopredators indirectly benefit from the decreased occupancy of the apex predators they compete with. This effect is displayed through the increasing co-occurrence of species such as coyotes, grey foxes, bobcats, and skunks with human activity. These results reflect the evolutionary impact humans can have on entire communities.

Mitigation efforts

Given that its effect on carnivores is evident and escalating, mitigation efforts are vital to consider as a response to urbanisation. Informed urban planning is one strategy for combating the evolutionary impacts of urbanisation. The most effective urban planning focuses on the areas and species most heavily impacted and at risk of extinction. Species that have limited ranges and available habitat are particularly vulnerable to the risk of extinction. As a result, the focus should be on urban areas that are biodiversity hotspots and hold endemic species.

Mitigation efforts should consist of protecting the habitat of endemic and range-restricted species and coordinating urban development to prevent contiguous urban clusters that hinder habitat connectivity. For example, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) incorporated urban conservation strategies into their global urban agenda. The 15th SDG aims to protect and restore biodiversity within ecosystems. This specific goal has several targets with indicators that set measurable outcomes of action by 2030.

While habitat protection is an important strategy to mitigate the evolutionary impacts of urbanisation, so is decreasing species’ attraction to urban areas. Species that have not successfully adapted to urban environments due to inflexibility in diet, movement patterns, and social behaviours can be negatively impacted by urbanisation. However, scavenger species such as red fox, coyote, Eurasian badger, and raccoon can achieve high densities within urban areas due to the ecological opportunity provided through food and shelter.

Additionally, large carnivore species such as bears, hyenas and wolves living adjacent to urbanised areas can benefit from scavenging opportunities. With this in mind, utilisation of urban areas may seem beneficial for scavengers. However, these outcomes can often lead to human-related killings, either due to conflict or encounters with man-made objects such as vehicles. Deterrents and reduction of feeding opportunities are two effective ways to minimise carnivore attraction to urban areas and anthropogenic mortalities.

Conclusion

Co-evolution between humans and large carnivores is a profound evolutionary dynamic due to the ecological roles of both interactants. In the early ages, both drove each other to adapt through an evolutionary arms race. In modern times, humans have the upper hand due to vast technological advancements. Urbanisation is an outcome that can have some significant impacts on large carnivores, such as decreased species richness, behavioural change, reduced gene flow, and increased species interactions within carnivore guilds.

With urban populations projected to become the majority, it is crucial to further investigate and mitigate the negative evolutionary effects and pressures exerted on large carnivores by humans. Given the critical role apex predators play in the ecosystem, the evolutionary effects on large carnivores may trickle down to the rest of the community in unforeseeable ways. Protection of natural habitat and behavioural aversion towards humans can serve to minimise interactions and evolutionary impacts. Simultaneously, further research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of these and other strategies as the issue of urbanisation continues to grow.

Further Reading

Carter, N. H. and J.D. C. Linnell. 2016. Co-adaptation is key to coexisting with large carnivores. Trends in ecology & evolution 31(8): 575–578.

Gámez, S. and N.C. Harris. 2021. Living in the concrete jungle: carnivore spatial ecology in urban parks. Ecological applications 31(6): e02393.

Hussain, S., M. Weiss and T. Nielsen. 2022. Being-with other predators: Cultural negotiations of Neanderthal-carnivore relationships in Late Pleistocene Europe. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 66: 101409.

Simkin, R. D., K. C. Seto, R. I. McDonald and W. Jetz. 2022. Biodiversity impacts and conservation implications of urban land expansion projected to 2050. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119(12): e2117297119.