Chokalingam was a very special character. Interestingly, his facial features somewhat resembled Australian Aborigine features. Like many Indian tribes, the Irula have become quite diluted as a particular racial type and in many, you have to look hard to see evidence of their Indian aboriginal ancestry. “Chocky” was one of the Irula instrumental in setting up the Irula Snake-Catchers’ Industrial Cooperative Society (ISCICS). Based on the Irulas’ superb knowledge of snakes, the Society would provide a livelihood for its members. But first, we needed to get them together. Chocky was one of my go-betweens. He also attended the early meetings with the Tamil Nadu Government’s Industry and Forest Departments. Chocky’s younger son, Kali, is the same age as my younger son, Samir, and the sometimes deadly mischief they got up to is a story for another time.

In those days, I was out with the Irula three or four days a week, learning what I could about their techniques in finding and catching rodents, snakes and other creatures of the farmlands and scrub jungle. When the Irula are walking along, they notice things that completely elude even weather worn and trained researchers: the smelly fresh scat of a monitor lizard, the smooth track of a snake on the edge of a rat hole (going in, or coming out?), a freshly shed skin hidden under the grass (a species we want?), fresh tracks, wisps of hair and live lice at the mouth of a rat hole, and of course, so much more in the way of edible and medicinal plants.

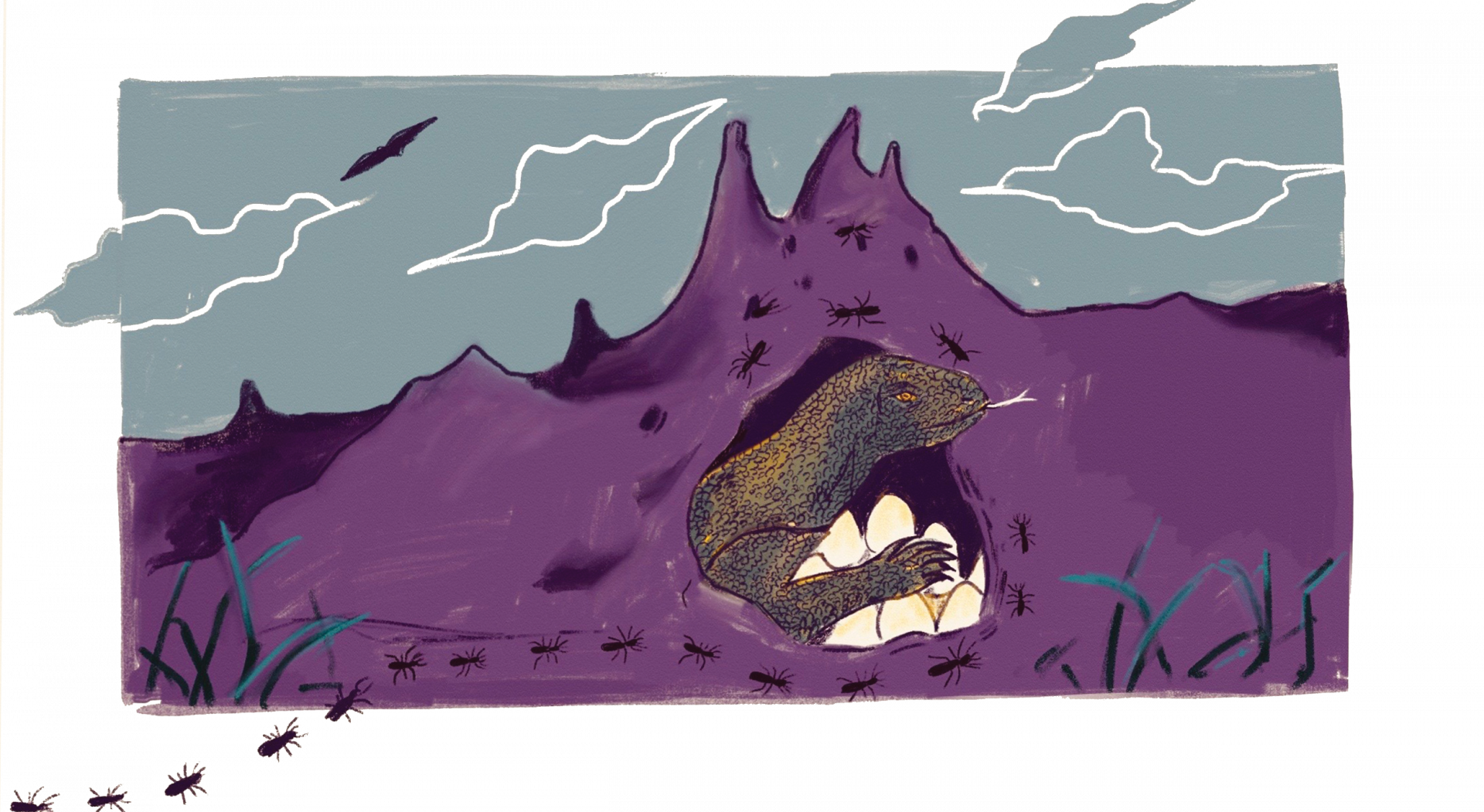

One day Chocky showed me a freshly repaired circular patch on a large termite mound. “Udumbu kudu” he said – a monitor lizard had dug a nest hole in the side of a termite mound, gone in, laid her eggs and departed and now, the termites had sealed up the hole thus securing the eggs from predation. Chocky explained that the monitors especially like to use the mound of the ‘black termites’ for nesting because these soldier termites are so aggressive that predators know not to mess around. Sure enough we found 10 long, leathery eggs which we collected and incubated. The eggs hatched a long 5 months later and we released the brilliantly marked young.

Walking along the densely vegetated bund of a small tank, Chocky suddenly stopped and pointed to something in a neem tree. “Pacha wona”, said Chocky. “A chameleon.” I expected to take a long time to find this wizard of camouflage, but there it was, in brilliant purple and yellow. It did not blend in with the surroundings at all! We both felt that there must have been another chameleon somewhere close by since this was the typical colour of a chameleon who had been fighting with a rival male. I’m pretty colour blind (reds and greens), so I never trust colours. But my eyes and brain seem to have developed a good ‘shape discerning ability’. Sometimes, when there’s a group of people with us on a reptile hunt and a chameleon is located, we’d tell everyone to turn around for a few minutes, and release the chameleon in a small tree. They would then have to find it again. The reptile’s ability to ‘disappear’ makes some of our guests take me seriously when I say, “It has turned into a big leaf on the tree”.

Some years ago, the ISCICS received an order for five grams of scorpion venom for a pilot project to produce scorpion anti venom. Apparently, the death rate amongst small children from scorpion sting is very high in some parts of India – the main culprit being the oddly-named Hottentoti tamulus, the common red scorpion known to all of us. Well, it was going to take about a 1000 scorpions to produce each gram of venom. How the hell were we going to find them? Chokalingam said, “No problem, if we put out a reward of Rs.5 per scorpion, the Irula will get 5000 within two months”. While some scorpions, like the large black ones, are tunnel diggers, the red scorpion seems to prefer hiding under rocks, plant debris and unfortunately, between the tiles on people’s roofs. Soon, the scorpions started coming into the ISCICS quarters by the bagful. We worked out a simple system of holding the wriggly little scorpions with a pair of forceps, tail-tip over the side of a petri dish. Then, by delivering a mild electric shock to the scorpion’s tail, a drop or two of whitish venom emerged from the sharp, curved tip of the stinger. The process was agonizingly slow but Chockalingam’s concentration and extreme patience formed just the right combination to make this venom extraction work really well. Within three months of receiving the scorpion venom order, the Irula had the five grams to send to the anti venom lab where it hopefully helped save children’s lives.

Chokalingam was an Irula medicine man as well and I once watched him treat a serious saw-scaled viper bite. An Irula girl had been bitten on the finger by a large one and her hand was badly swollen. I asked if we should take her to a hospital, but Chokalingam was adamant that he knew how to treat her. Wrapping a cord around her forearm, he made tiny slices in the webbing between her fingers with a bit of broken glass. By increasing the pressure of the cord around her arm, drops of blood and clear serum exuded from these little cuts. After that, he wrapped her entire arm in a cloth filled with a poultice of black turmeric leaves, which was to stay on for three days. After the poultice was removed, the swelling had all but disappeared and there was no doubt that the wound at the site of the bite was healing well. The wealth of Irula tribal medicine got a considerable fillip when the Irula Tribal Women’s Welfare Society (ITWWS) was started at Thandarai at the instance of Zai Whitaker, and we still have plenty to learn from these amazing people.

A bonus from knowing the land, its plants and creatures were the edible titbits that came our way while walking the countryside with tribesmen like Chokalingam. The yam the Irulas call Velli-kodi kizhangu is, they say, what they used to survive on before rice became the staple. Finding a vine with typical heart-shaped leaves, Chocky would carefully dig until the fat root was exposed. He would cut the main root off and bury the top of the root to which the vine was attached. “The root will grow again,” said Chocky. All I could think of was, “Am I looking at one of those first instances of agriculture? Is this perhaps how agriculture began?” We collected berries like the syrupy sweet gunja-pazham, savoured the sharp tartness of small black thorny berries called sura-pazham, the carrot stick refreshment of gnawing on a bit of ‘sappathi kalli’ (a type of spineless cactus flower) and it was all good. But these pale in comparison to the ‘honey experience’.

Often, on a long tiring walk, Chokalingam would keep his eyes tuned to finding some ‘kutchi-then’ (stick honey). These particular bees make their small honey comb on a straight stick conveniently at eye level, not way up in a tree nor in a hole. They sting like most other bees, but by gently blowing on the hive the bees are persuaded to fly away. Chokalingam cut both ends of the stick with his aruval (a curved machete) and brought out a turkey drumstick-sized honeycomb…ooof! Under the honey-packed wax cells of the comb, there are often bee larvae, one in each cell and especially prized by Irula children. If we were hot, sweaty, and hungry after half a day of walking, biting into that honeycomb and letting the honey drip down from your lips all the way over your fingers was heaven. I was tempted to slurp like a child. “No, don’t do that”, warned Chokalingam. “If you slurp the honey like that, you can choke.”. That’s what happened to me one day and it was fixed by a good slap on the back and a sip of water.

I was and am still amazed at the Irulas’ ability to find and capture rodents. For a tribe that made its name in conservation for their scientific love affair with snakes, their knowledge of every other species that they interacted with always astounded me. I was sure they could do a better and safer job of rodent control than the pesticide people that most of us are keen to constantly hire. When Chokalingam and I were invited to the Central Food Technology Research Institute in Mysore, Karnataka, he displayed his skill and understanding of rodent behaviour and caught a batch of 28 lesser bandicoots plus several gerbils in just one afternoon of digging up burrows. After a few more field trials, we received a grant from the Department of Science and Technology for a serious rat project. During the year-long rat hunt, the Irula caught a quarter of a million rats and recovered close to five tonnes of stored grain from rat burrows. We dug out entire rat burrow systems, mapped each one of them and learned a lot about the habits of the four main species affecting crops in our area of Tamil Nadu. The next phase was to set up a bio-control company owned and operated by Irulas, but it never happened. I thought that we had proved the effectiveness of hands-on rodent control without having to use dangerous pesticides, but I guess there is big money in the pesticides industry and our enthusiasm just died without support for the idea of applying the Irulas’ tribal technology to a problem that may account for the loss of a quarter of all the grain we produce in India. Is there anybody out there interested in our idea of promoting the Irula Pest Busters?