I’m seven. I’m spending the vacations with my grandparents in a little peri-urban village that will soon be digested within the messy innards of Bombay.

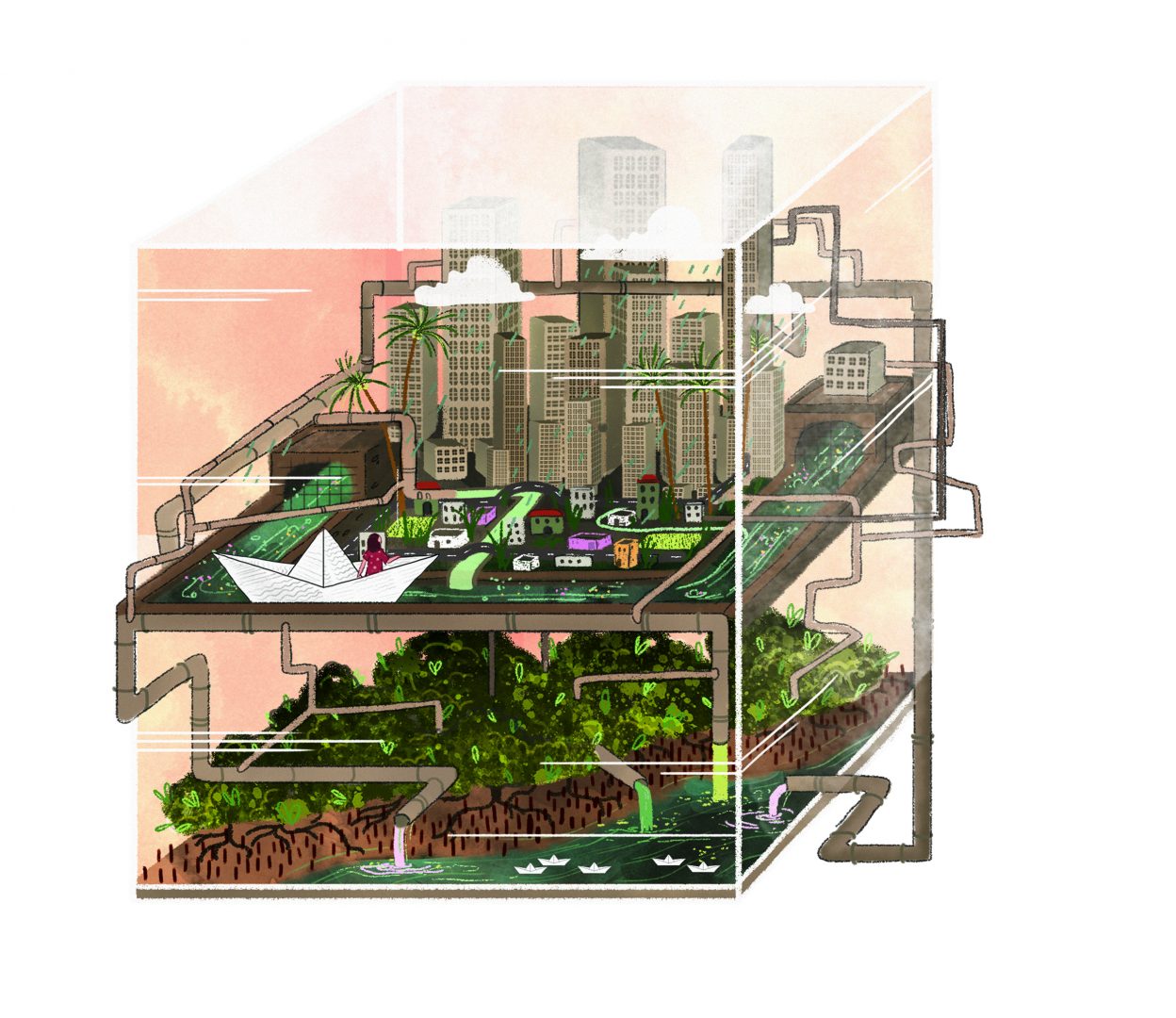

The village is my landscape of summer dreaming. Outside the garden gate, down past the dirt track that leads to the asphalt road, there is an open storm drain. It collects wastewater and sewage, swilling together the private leavings of the nearby houses. It flows past our little lane but connects to a larger drain on the main street, which is connected yet again to other tributaries in a dizzying network that pours untreated waste into the ragged mangrove patches near Versova, finally trickling into the Arabian Sea. It ebbs and flows with a rhythm that links the daily ablutions of the village with the rain and the tidal cycles of the Indian Ocean. Some days, for reasons my seven-year-old mind cannot fathom, it is less of a flow and becomes a thick slurry, bubbling and burping ever so slowly, an enticing, glistening black. At other times it is a clear sap soup, getting clearer each time it rains. When grease from the kitchens pours in through the drains, an oily rainbow flits on its surface and I can play with it, disturbing the vibgyor with a stick, watching it form again lower downstream. Mostly though, the stream is a dark, slightly viscous indigo. In the neighbourhood, it is called the Gutter.

The Gutter is the subject of folklore in the village. Of lost treasures big and small – four anna coins and engagements rings. Of late-night drunken stumbling and mucky ankles. Of the sad village idiot called Gutter-Bamboo, who spends his day poking about it with a pole for anything he can find. For me, the Gutter is a place of endless fascination. Each morning, I rush out the lane to check on the progress of the stream, make a mental note of its colour, its texture, any subtle change in odour.

My dad has bought me a book called ‘Origami for Beginners’. Tearing out pages from my double-line notebook, I follow the instructions. Square folds, mountain folds, unfolds – and I have my first origami boat. A trifle wonky, but I’m proud of my craft. I rush down to the gutter to float it. It is glorious in the stream – wafting on an ebony river, down to where it meets the larger tributary. Buoyed by this success, I grow in my naval ambitions. I spend the rest of the morning building an entire armada with boats of different sizes. I make small triangular flags for the larger ones, borrowing a few sticks from grandma’s broom for the masts. The tinier craft requires more skill I realise, but my fingers are small and deft. I colour these little ones with felt pens in bright primaries.

By evening I have an entire fleet, including a large flagship made with a piece of chart. It has a proud mast, portholes, and, in an inspired touch, a forward cannon, made with leftover bits of paper. I sleep the sleep of a master shipwright, pleased with his craftsmanship. It rains all night and the gutter is in spate. Still, by 11 am, the floods have calmed a bit and I am ready with my fleet. One by one I launch the ships…all 17 of them, from flagship to little skiffs. They start off in a proud orderly convoy, but quickly bunch together in the centre of the stream. At the confluence, I watch the messy flotilla get taken over by a more furious flow. A few of the small skiffs overturn and sink, but the hardiest rough the waters into the distance. I’m not allowed to venture far down the main street so I watch as my brave fleet floats and bobs its way to grand adventures out toward the ocean.

I’m older now. On a small island in the snapping jaws of the Gulf of Kutch.

I’ve been here several months, and I’ve made it my home. “Are you coming?” asks Dadi. “Yes, I’ll be right there”, I say. Dadi and Dada are my adopted family on the island, and I’m helping Dadi in her daily beachcombing. Every day, the tide goes out for several kilometers. Then swarms back to shore with the force of a river, bringing with it a scattering of debris. Every evening Dadi and I walk around the beach, picking up bottles and putting them in a large gunnysack. I try to imagine how a modern-day Crusoe would construct the world from all the stuff that floated to his castaway island. Urgent empty missives delivered in a torrent of Pepsi and Bisleri bottles. Our beachcombing is not a cleanup exercise. It is a gathering expedition, a way to gain a small supplementary income. On the mainland, Dadi gets 25 paisa for every undamaged bottle she finds, more, if it has the cap on. Within a fortnight of collecting, we have enough for several hundred rupees.

Dadi has spotted something in the distance, near the lighthouse. We rush to see what it is. A small wooden crate likely dropped from a passing ship. It’s been floating for a while because it has algae and a few bright barnacles growing on it. I drag it to the Porta Cabin and, between Dada and I, we break it open. It’s a 12-pack of pear juice, not yet past its date of expiry. We are ecstatic. We tear into one and taste it, gingerly at first but then with greedy gulps. It is delicious. We have no refrigerator, but there’s a spot beneath the mangrove where it’s always cool. For four days we feast on the best pear juice known to man. There’s treasure everywhere.

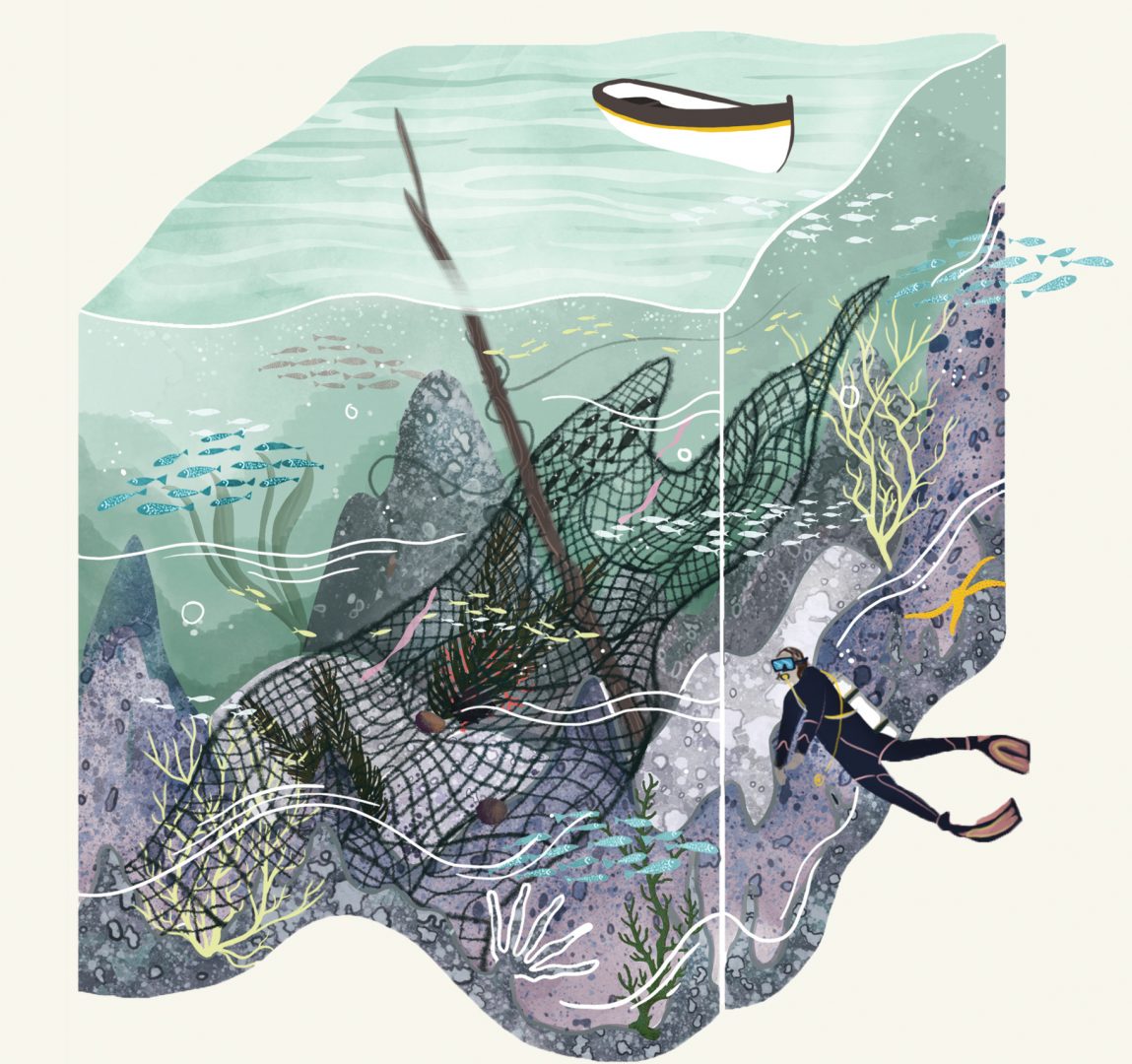

I’m older still. We are diving off Kiltan atoll in the northern Arabian Sea, trying to take stock of the reefs after the last massive El Niño event.

The coral itself is struggling, but for the most part, the fish don’t seem to care. There’s bustle everywhere as the fish wander through their metropolis. Skulking in ambush among the boulders, busily scraping the turf, getting parasites removed at cleaning stations, angrily shooing away territorial invaders. They barely mind us, gawky camera-toting tourists. The reefs of this archipelago are climate-weary after repeated battering, but at least on this reef, things are not so bad. We are in expedition mode so we have to work efficiently. Everyone knows their job – who lays the transect, who takes the benthic pictures, who counts the fish.

Transect three. Something dark and ominous against the blue. We all spot it together and our eyes widen. A gigantic fishing net has drifted in from the deep and is trapped on the reef. It has caught on the coral at around 15 m and rises all the way to the surface. It sways gently in the swell like a single incongruous and impossibly-large kelp, reaching to the sun. It has reaped a rich bounty in its journey to the reef. Snappers, jacks, a few fusiliers, a massive tree trunk, fronds of coconut, all bound together in its gills. We abandon our transects. Despite ourselves, we are drawn to it, unable to take our eyes of its sheer majesty. We spend the rest of the dive circling the net along with schools of batfish, inquisitive unicornfish, triggers, and a host of other worshipers.

With a totem of this power, all you can do is pay quiet homage, and marvel at its extravagant, wasteful beauty.

I’m travelling on the Ganga in Bihar. The river is a clayey green and there’s debris everywhere. The Ghats are densely concentrated with plastic and micropackaging. Walking to the river’s edge, we must navigate the garbage and ritual offerings strewn along its banks. It has all the floral colours of spring, only brighter and more arbitrary. I’m sitting now on a little boat in the middle of the stream, quiet and happy. The gutka packets on the shore glisten gaily in the morning sun. I imagine the river goddess, vain, proud, self-aware in her own dramatic beauty. She is picking carefully through her vast jewelry case of intricate debris, lining her tresses with gaudy glitter, smiling at her reflection, clearly pleased with the result. A large bloated buffalo wanders past our boat. It has been dead for a while, and it floats content in its gentle passage. A river dolphin surfaces, snorts, and disappears. A bucolic idyll.

I have my notebook in my hand and something inside me wants to tear a page, make an origami boat, and float it down the river.

But I’m not seven anymore, so I don’t do anything of the sort.

In my imagining though, my little boat navigates its way around the dead buffalo, past the Farrakka Barrage, through the crocodile-filled waters of the Sundarbans, into the raging Bay of Bengal to find its home eventually among the eddies of some undiscovered garbage patch in the Indian Ocean where all paper boats, Pepsi bottles, phantom nets, gutka packets, and dead buffaloes eventually land up, along with the rich histories that brought them there, swirling together.