So, one Sunday afternoon, I go to the bull-fight and they put me in the bullring. The bull comes out. I look at the bull and the bull, he look at me. He look at me, and I look at the bull. And you know what, the bull was better looking than me.’ -Juan Cervantes, Mind Your Language, 1978.

We’ve been mulling over our recent posts with a seed of doubt in our minds. We cannot help but notice that our writings may have aggravated animal rights activists, castigated compassionate conservationists, and berated vegans and plant lovers. To our critics, we clearly voice irrational arguments and cross-eyed views of the world.

So we’ve tried a thought experiment. We have simply asked: ‘What if they are right?’

Well, then, every animal must be given its due. Each one is a product of hundreds of millions of years of evolution on Earth. The history that each individual carries in its DNA, the carefully selected genes of the blind watchmaker, the memories of each moment of its personal journey must be celebrated, revered, venerated.

But what, practically, must follow from such sentiments? Perhaps the most important point is that it means that we must respect each animal not from our narrow anthropomorphic, anthropocentric perspective, but from the view of animal itself, of nature herself, of the watchmaker her/himself. And this in turn means that we must dig deeper into our engagements with the animal world, and rip out the very roots of these abusive relationships. This leads to a few inescapable conclusions, a trilogy of four to be precise.

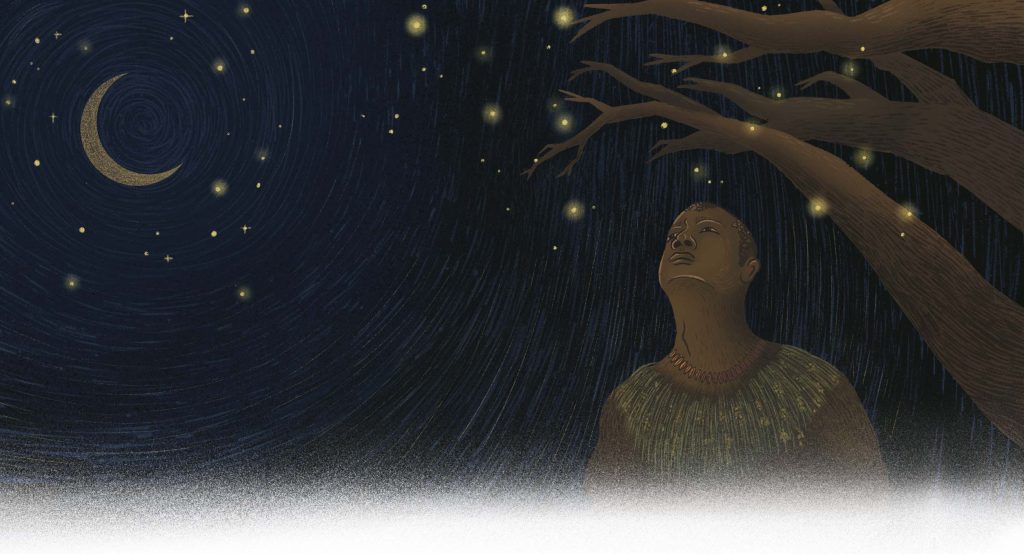

First, no wildlife watching. Quite simply, wild animals don’t like to be looked at. For most vertebrates, direct eye contact is a sign of aggression. Their motto is ‘Don’t be looking at me that way. In fact, don’t look at me at all’. And even in the absence of actual eye contact, being closely observed by a human (or worse, a flock of them) is almost a clear signal of predatory intent. Thus begins the physiological domino. It starts so simply, each line of the programme creating a new effect, just like poetry. First, a rush… heat… her heart flutters.1 And as the cocktail of chemicals floods the system, lion or lizard, fish or flamingo, she runs. All this stress from one little self-indulgent, greedy glance.

So, unless one is planning a romantic moonlight dinner, people should not look at wild animals at all. No more wildlife voyeurism, no bird-watching, not a single dive to scare sleeping parrotfish.

Second, no more domestic animals (with the exception of cats, who quietly decided that the comforts of domestication were suited to them). After all, they did not exactly ask to be domesticated. Of course, the only one who truly embraced the consequences of domestication was the cow at the restaurant at the end of the universe, which approached Zaphod Beeblebrox’s table ‘a large fat meaty quadruped of the bovine type with large watery eyes, small horns and what might almost have been an ingratiating smile on its lips.’

“Good evening,” it lowed and sat back heavily on its haunches, “I am the main Dish of the Day. May I interest you in the parts of my body?”’

Chickens get no evolutionary love from laying unfertilized eggs, nor can cows fatten their calves with dairy products. We should release them all into the wild, and allow them the unbridled joy of the wild’s consequences.

And no domestic animals also means, by the way, no pets. No self-respecting animal wants to be reduced to an emotional appendage. Caged and cuddled alike, every animal aspires to be master of its own destiny. As brief and bloody as it might be. Set them free, we say. Let cats run wild and decimate bird and lizard populations around the world, even more than they do now. Let packs of dogs roam our streets and pick off the cats, and the occasional child. Let hamsters….

Finally, why stop at animals? We must also free plants. Gardens are basically glorified factories, exploiting sentient life forms for their colour, scent and form. Plants are pruned mercilessly without the remotest jot of participation, or prior-informed consent. No gardener has ever, not ever, used the word ‘holiday’ to her geraniums. Enough, we say, enough.

Fifth and mostly harmless, alien life forms. We wish to leave no stone unturned in our efforts to minimize human impact on life everywhere. Should there be an invasion by universe conquering computer geeks , every carbon-based multicellular life form must be received with the same respect and treated with dignity, regardless of their intentions. We do have to draw the line somewhere. Unicellular organisms and life forms based on other elements – Silicon’s campaign notwithstanding – simply do not cut it.

Nuff said.