Sheep’s brains, fresh tomatoes and Panglossian delusions

Pont de Molins is barely a village. On a small bylane that branches off the main highway between Figueres and France, there is little to distinguish it from the hundreds of half-abandoned settlements across the length and breadth of Catalonia. For a few months in July and August, the houses fill up with summer migrants from Girona, Barcelona and beyond, and then the village retreats to itself once more.

We are spending the week a few kilometres away and Molins is the closest place to stock up provisions. Teresa has me on a diet of soup and grilled vegetables. It is good for my health, but it saps my soul. Worse, I am even half starting to enjoy it. In a desperate bid to nip this distressing development in the bud, I point to the sign on the butchers’ door: We sell fresh tomatoes from our farm. The door has one of those simple clanking bells attached to it, and as we push it open, it rings loudly. From somewhere in the back, a voice shouts out to us telling us that he will be with us presently.

The shop is sparse. Sections of steak and a few portions of deboned chicken lie in the meat counter, covered with white muslin. Salted bacalla. Several cheeses, cartons of eggs, one or two pates. A few fuets, llangonestes and other sausages drying on a wooden pole. A row of homemade pickles. And a worn woven basket with those advertised farm fresh tomatoes. The butcher emerges through a door behind the counter, rattling through a faded bead curtain, the quintessence of butcherhood. Large, but not obese. A friendly double chin that rests directly on his shoulders. A horsey smile with a prominent gap in his teeth. An old but clean apron. A cleaver.

We choose our tomatoes, and, as the butcher weighs them out, I lead Teresa gently to window shop the steaks at the meat counter. After fourteen years, I don’t need to say a word, and the lady relents. Alright, she tells the man behind the counter with a resigned sigh, carve us four of those steaks as well, and make one thicker than the rest. There follows a long discourse on the weakness of men, their lack of self-discipline, and their inability to look after themselves. The butcher gives me a sympathetic fellow-sufferer look as he carves out the steaks, and makes placatory noises in Teresa’s direction. He wraps up our packages.

We are about to leave with our purchases, when Teresa spots them in the corner of counter. Brains. Two small sheep brains, resting together, bound in cling film. We start a conversation on the business of brains. My own thoughts wander across the continents back to the streets of Bombay, and the textures and spices of Bheja Fry light up gustatory memories on my palate. It is a dying tradition here in Catalonia, the eating of brain, and it has been more than a decade since Teresa last ate it.

My mother, says the butcher, makes a delicious bunyols de cervell. Hang on a minute, I’ll call her. Mama, he shouts at the bead curtain. Can you come here a moment – we have customers wanting to know your recipe for bunyols. A minute passes, and a silver-haired lady parts the curtain, dusting her skirt. For the next 20 minutes, as I try, with my limited Catalan, to follow along, the three of them discuss the proper way to make bunyols. Here, in Ponts de Molins, says the butcher’s mum, we puree the brains before frying them. Two eggs. Flour. Salt. Some olive oil. Couldn’t be simpler. But, she says, made right, the bunyols de cervell from Molins are like bunyols nowhere else. This is said not with any sense of pride, but with a self-assured certainty.

It is a certainty I have come to know quite well in the relationship that the Catalans have with their cuisine. And at first glance, it is easy to dismiss this, a simple Panglossian delusion of a community convinced that their accidents of birth have landed them in the best of all possible places, in the best of possible times. But there is more here. In the Catalan spirit, a dish is an organic being, born of the land and waters from whence it came, and, cooked well, it takes credit for itself. The chef is merely a vehicle for its expression. Every pod of garlic and every tomato in the dish should speak of its origin. And the ingredients of a region are not just better than the province just next to it – they are the best you can get anywhere. So it is only natural that when mixed together by hands that know these products well, they will transubstantiate into something of transcendent perfection. By this token, a recipe is not merely a set of instructions for a meal, but a visceral philosophy that links you to the soil on which you feed your palate.

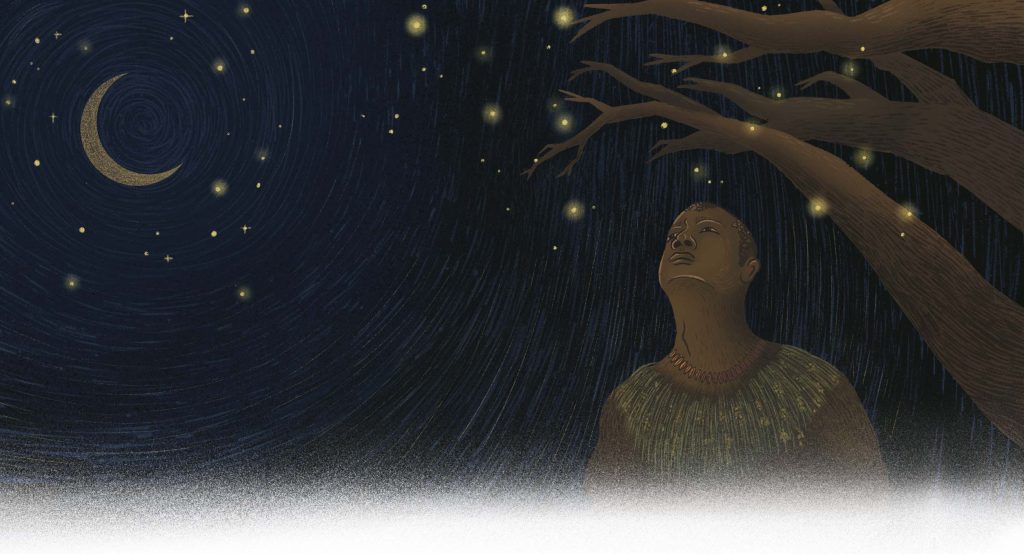

It is evening, and we sit in the kitchen, watching the long summer day draw slowly to a close outside the window. Teresa sets the water to boil, and I take a few eggs out of the fridge. The olive oil in the pan is the colour of the river that flows outside our window, full of autochthonous reeds. Fried, the bunyols are a golden crisp, a gentle homage to the sun setting over the pre-Pyrenees. Before they can cool from the pan, I take one and bite into it. In this landscape, at this time of evening, there could be nothing more perfect. Somewhere here, surely, in this moment of contact between sheep brain and human tongue, lies a deep secret of endemicity. I succumb to the Panglossian delusion.