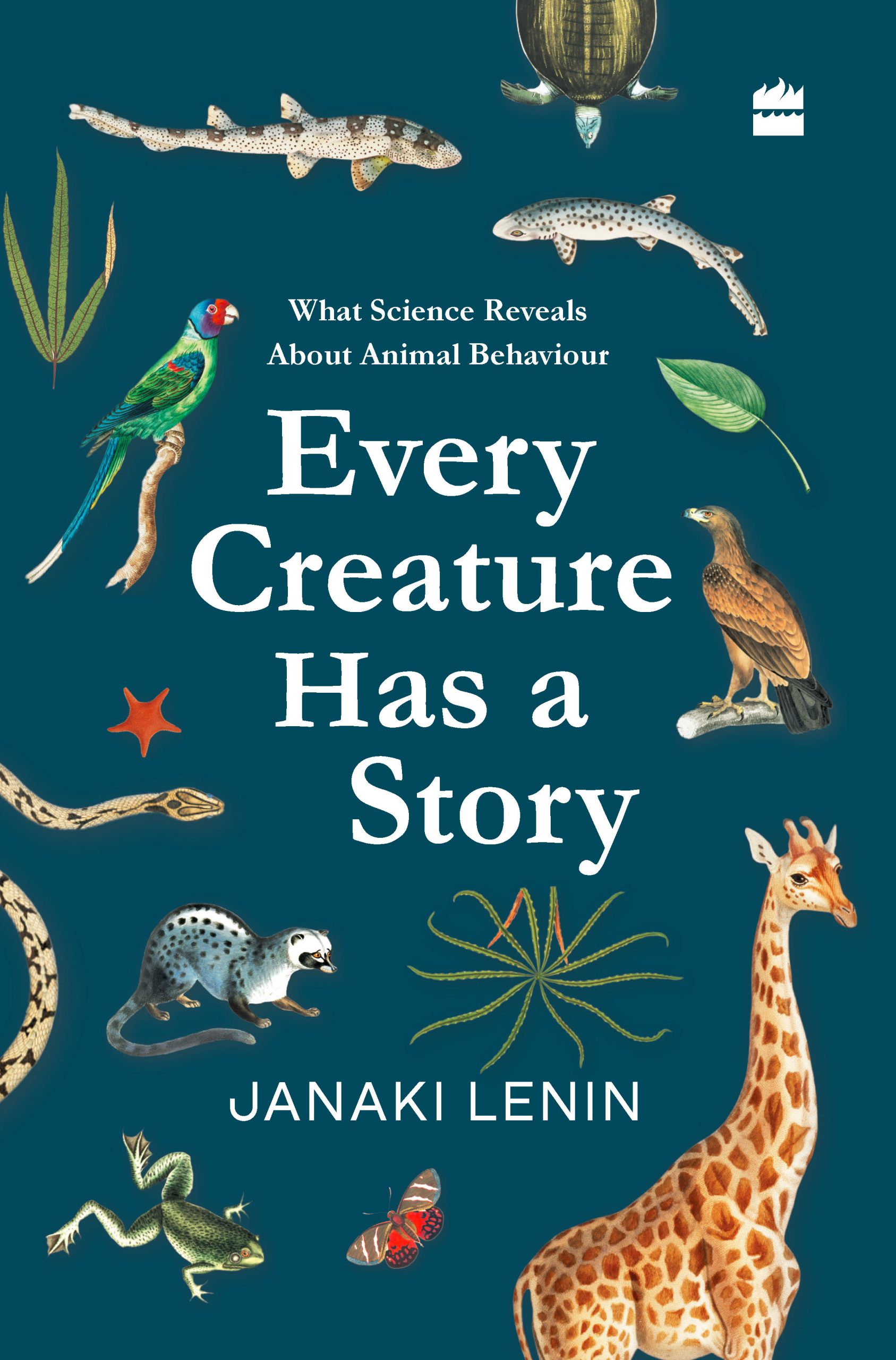

You know how the saying (kind of) goes, ‘Always judge a book by its content page?’ That is at least what I was thinking when I started reading Janaki Lenin’s book, Every Creature Has a Story. Not only does it have a beautiful cover, it has a riveting Contents page. Here are a few examples–

Airborne Sleep

Sticklebacks Hold Their Water

Wasps Enslave Spiders to Weave for Them

Pregnant Fathers

Laziness Has Its Uses

Did Moby Dick Sink the Pequod?

And it just gets better from there. Underscored by a tagline that tells readers, What Science Reveals About Animal Behaviour, author and filmmaker Lenin’s book is a collection of 50 essays, updated and selected from her column in The Wire. Lenin’s series offers a fascinating understanding of animal behaviour, while breaking down complex science and research for the reader.

For instance, in ‘Rodent Monogamy’ Lenin considers the question of what makes some prairie voles ‘stick to one mate and the others wander?’ Explaining research that otherwise would be gobbledygook for many of us, she explains the way vasopressin, a hormone produced by the hypothalamus influences social behaviours. It’s enthralling stuff, suffused with generous doses of humour and insight.

I was fascinated by ‘The Scent of a Fur Seal’, where Lenin writes about the curious case of Antarctic fur seal mothers being able to locate their offspring after having travelled as far as 240 km over five to ten days in search of food. Countless documentaries came to mind as I read this chapter slowly, taking it all in. As a children’s book author, I have always read in stories on how seahorses make for great dads, as males are the ones who get pregnant. Lenin talks to Camilla Whittington and her colleagues at the University of Sydney, Australia, to understand this better. Including how on a full moon night, the father produces ‘isotocin, the fish equivalent of oxytocin’ to induce labour. Never looking at a full moon night in the same way again! And that a ‘big-belly seahorse dad’ can produce some 1,100 babies.

Another example of good paternal behaviour that Lenin cites is that of ‘young male moustached warblers’ who, if the fathers do a runner, step into incubate eggs, feed the female’s young chicks, and keep predators away. Surrogacy in the bird world, who’d have thought that there were so many examples, and such sound reasons for them.

There are lots of aha moments in the book, awe-and aww-inducing ones as well. Like when Lenin explores the question ‘Are Humpback Whales Altruistic?’ It turns out, they do go out of their way to rescue their own kind, and sometimes other creatures! Marine biologist Robert Pitman, who is with the National Marine Fisheries Service, US, offers insight into their Good Samaritan motivation—along with his colleagues, he has compiled some 115 cases of humpbacks confronting killer whales in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

From looking at bird song to parenting behaviour and literary history to prey-predator relationships, the author takes on complex subjects with panache and offers scientific reasoning and research in each essay, separating fact from anecdotes. What’s also fantastic is that Lenin delves into different species, but mostly she looks at oft-ignored ones—from ants to snails and shrews to wasps. It’s bizarre, it’s enthralling, and it’s witty. And she does all of this with clarity and a scientific curiosity which is really infectious.

In her Introduction, Lenin admits that it hasn’t always been easy. The basis of the essay was a column, which means short deadlines and so she appreciated the chance to ‘update and tinker’ with stories for the book. ‘As if the challenge of getting the science right and communicating it accurately weren’t enough,’ she writes, ‘I also aspired towards another goal—to entertain and connect with readers who knew nothing about the animals.’ That is a good goal to aspire to, and Lenin achieves it and how.

Also, I must admit, having this book in hardback, given that it’s so beautifully produced (not to mention extensively researched), makes it a joy to hold and read.

When it comes to animal behaviour, few Indian books approach the subject from the lens of science for mainstream narratives. Usually these strands are restricted to academia, which is why Every Creature Has a Story becomes something of a landmark publication. Especially at the time it has been published—we’re entering into what is now being called as the Sixth Extinction, we’re firmly in the Anthropocene, not to mention a pandemic, and it’s become imperative, as developmental biologist K Vijay Raghavan, in his foreword to the book writes, ‘to understand earth’s many remaining natural wonders better, even as we strive to restore it to stability.’ And Every Creature Has a Story does just that.