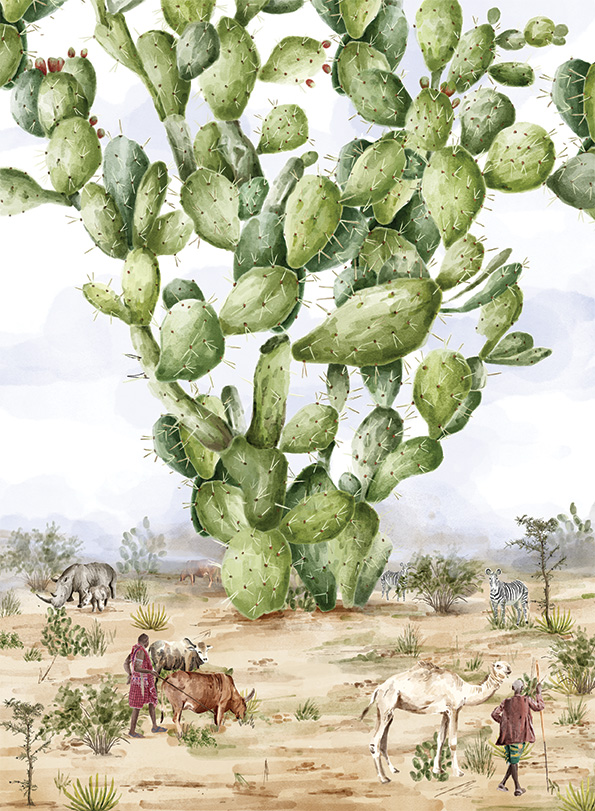

Weekend getaways to refresh oneself in the lap of nature have become an increasingly common occurrence. However, what if one were told that cities are, in fact, teeming with diverse life forms if we ever stopped to notice? What if the simple act of growing edible food in small pockets around the city could become tiny hotspots of wilderness? Rather than seeing nature as something separate from human habitation, what does it mean to understand and appreciate the ecosystems existing in cities? We reflect on these questions through our own experience of urban farming and attentive walks around the city of Mumbai.

If you look at it long enough, there is a strangely hypnotic quality to a spider’s web. We have spent countless moments mesmerised by the poise of a signature spider, as if deep in meditation. Its uniquely patterned web glistens in the sunlight like fine threads of silver. The trance is broken soon enough by the emphatic alarm call of the tailorbird that is fiercely guarding its nest in a nearby balcony. Tailorbirds, though tiny, produce loud calls that are heard all over the city. We were amused to see something that small being so loud. And there are many others like the tailor bird, who may be small and “insignificant”-looking, but their presence is felt through the many signs they leave for us in the form of songs, feathers and nests.

Contrary to popular belief, cities nurture much more than human life, and can do even better with a little participation from our side. Often, the simplest way to make space for nature in cities is by observing it. This has proven to be true in several ways during the lockdown period, as people find themselves paying attention to spaces that often go unnoticed. The black kite that usually soars up high in the skies is seen relishing an assortment of prey with each passing day, ranging from rats to lizards, birds and fish! With all kinds of wilderness encounters across different cities featuring in the news, the promise and possibilities of urban biodiversity hide in plain sight.

Right before the lockdown, we were caught off-guard at the sight of a young jackal foraging near some trees in suburban Mumbai. It was difficult to say who was getting more attention, us or the jackal, for both spent several minutes following the other, until the jackal finally decided to disappear amongst the thickets. Our non-human companions give us company, even if we do not notice them most of the time; like the rose-ringed parakeet who secretly munches on all the guava fruits on our institute campus on the hottest of afternoons.

One of our favourite evening walk routes goes through a now largely abandoned residential area in the city. Apart from a group of wild pigs and dogs, the area is home to coppersmith barbets, Tickells’ blue flycatchers, Indian silverbills, common ioras, scaly breasted munias, ashy and plain prinias! Once, we spotted a spectacled cobra lazily cross a road and enter a garbage dump, perhaps having made a quick meal of another snake or a rat. In fact, once your senses are attuned to picking up signs in the environment, it is incredible how much a simple morning or evening walk can reveal!

Not just a concrete jungle

Apart from passive observations, it brings us no small measure of joy to witness things growing. Growing edible plants is a uniquely rewarding activity as one gets to experience various connections involved in the journey of food. Pay close attention, and the soil comes alive with hundreds of critters engaged in constant action. A million more are not even visible to the naked eye. We never knew how beautiful okra flowers look, or how the Amaranth plant yields thousands of small, round, shiny black seeds. Digging for tubers felt no less exciting than a treasure hunt, and the resilience of an ash gourd vine that had endured the trauma of being trampled upon as a sapling surprised us no end. It eventually bore over 10 ash gourds weighing between seven and 18 kg!

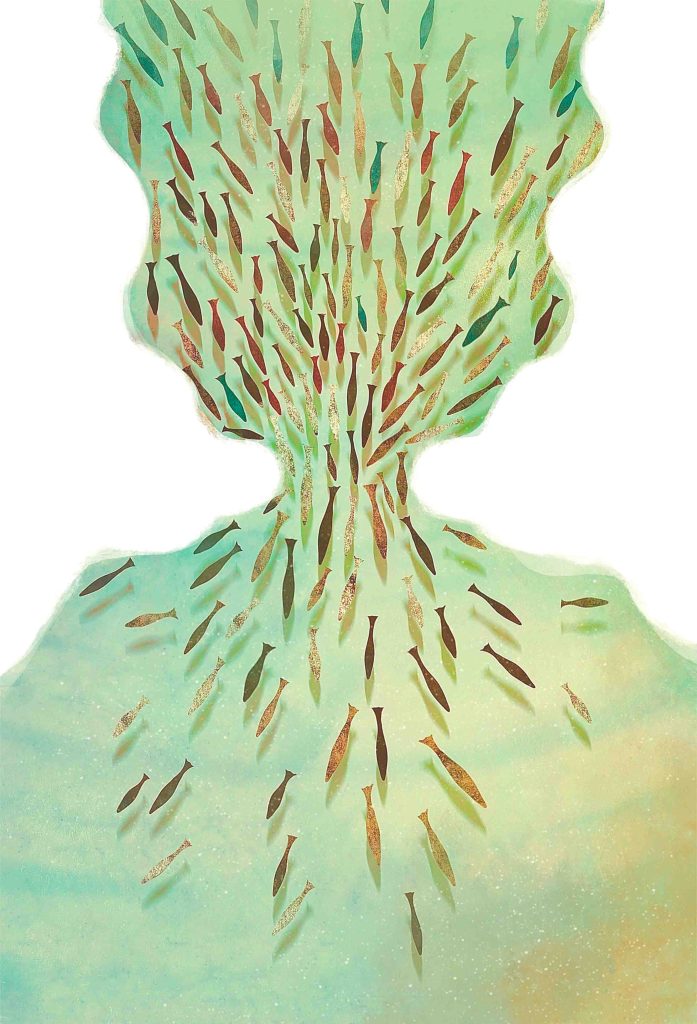

As the plants have grown in a tiny corner of the academic campus, relationships have become more apparent too. Ants can be seen stroking the underbellies of aphids to stimulate the secretion of plant sap that the aphids feed on. Plants are not silent spectators either. We always wondered how ladybirds would invariably be seen on plants that had too many aphids on them. Numerous studies now show that plants release volatile compounds that attract predators of the pest, and can also warn neighbouring plants! There is much that goes on beyond our sensory perception, but close attention can allow us to appreciate things that we would otherwise miss.

Termites seem busy at work, decomposing layers of organic mulch almost as fast as we can add it. We often spot the common Mormon butterfly hovering around the curry leaf plant to lay eggs.

A wasp quickly catches a leaf miner and flies away, before it becomes a meal itself for the ever-watchful bee-eater. The orb-spider patiently waits for a grub to get caught in its web. A family of mongoose stick their heads out of a burrow, perhaps as curious about us as we are about them. We play a staring game with them being absolutely still and rejoicing quietly when we win. Winning here essentially means the mongoose are no longer wary of our presence and go about their daily activities ignoring us. We make peace with the monkeys who have developed a taste for our brinjals and cabbages. We are thankful that they usually leave our beloved tomatoes alone! After all, we are newer occupants of the land that they had inhabitied long before us. We rarely encounter snakes on the farm, but they let us know of their presence through several feet of (shed) snakeskin lying close to the rough surface of the building wall. The web of relations continues to grow.

Rewilding our cities

There is an old mango tree in our neighbourhood. Apart from its majestic canopy, it is well known as the roosting site of hundreds of black-headed ibis, night herons, glossy ibis, and cattle egrets! The timing of the ibis is impeccable. They arrive in flocks of 10—15 from nearby wetlands and circle around their favourite tree. They soon settle on the tree, occasionally fighting off crows or black kites. It is a mystery how and why they choose those particular trees. Some explanation might exist somewhere, but it won’t do justice to the sheer experience of watching these beautiful birds gathering around the tree at dusk, as if it were calling them to rest for the night.

There is no dearth of life even in what we may consider the filthiest of habitats in the city. Amidst the murky waters of the sewers and gutters we find between railway tracks, we see tiny frogs popping their heads out. In garbage dumps, we find the opportunistic cattle egrets scavenging along with the crows. And in wetlands that are greasy with oil and cluttered with trash, we find waders filtering the food from the rubbish. Some of these areas are invariably flecked with pink as they become the wintering grounds for many lesser and greater flamingos. The migrant populations of birds visiting the city time and again give us hope that we can, perhaps, share this space with them. Even in the darkest corner of a building, an owlet moth mesmerize us with its psychedelic patterns.

However, we must recognise that we can’t take their companionship for granted. As in any relationship, this needs some work from our side. We can actively create habitats that allow diverse species to flourish, even as our hearts and minds expand through such efforts. From balcony gardens to terrace farms, river banks to wetlands, every ecological niche makes a difference. Distant hills and forests are undoubtedly alluring places, but cities need not be bereft of wonder either. In rewilding the spaces in our city, we might find the humanity that is often missing in it.