As a child, I was lucky enough to grow up in a metropolitan city while also having a forest in my backyard. Since I can remember, insects and all “bugs” have been my favourite creatures on the planet. I would watch ant colonies for hours trying to determine how their system functioned, collect praying mantises or crickets to observe their behaviour, and watch spiders spin their victims in webs.

I was surprised to learn that others did not feel the same, even those with access to nature at their doorstep. One time at school, I was quietly observing a bee that was either exhausted or dying. Out of nowhere, someone ran up and smashed it with their foot. I was shocked and angry but struggled to explain why I was so upset. The person laughed and said that it didn’t matter anyway. Another time, my mom was sunbathing in the backyard and I was so excited to give her two presents: one hand full of rolly pollies and the other full of worms. I was confused by my mom’s disgust with the gifts.

After other similar incidents, I decided that if others did not want to be around bugs, I would make being around bugs my entire life. I knew that I wanted to help educate people about the importance of bugs. At that point, I wasn’t quite sure how I would do it, but I talked to anyone who would listen. No matter where I went, people would tell me about their dislike or fear of bugs, but I was also able to find those who loved them as much as I did.

Insects and other invertebrates are the most populous animals on earth, yet are rarely the focus of conservation efforts, with the exception of a few well-researched species like honeybees. There are many reasons for this, including a poor understanding of these species, difficulty in specifying a single species for conservation, and a lack of interest in insects by the general public. Bugs are a vulnerable group who are often overlooked and underappreciated.

The field notes that I have collected over the past year weren’t from some distant land, but instead from the city where I live—Denver, Colorado. While exploring rainforests and faraway lands is extremely important, discussing wildlife and conservation in urban spaces is equally important but less often done. More and more land is used for infrastructure, not for urban parks and open spaces. It is estimated that by 2050, 69 percent of the world and 89 percent of people in the US will live in cities. Dunn and colleagues (see Further Reading section) presented what they call the pigeon paradox: as human populations shift to cities, humans will primarily experience nature through contact with urban nature. Without the understanding and help of people who live in urban environments, we doom ourselves and all other species.

Why the hate?

Two Japanese researchers came up with the urbanisation-disgust hypothesis: urban living creates situations in which people encounter insects indoors more often than outdoors, and they also lose the ability to identify them. This leads to a more intense and generalised disgust of insects (and other “bugs”). They also state that urbanisation reduces insect knowledge which contributes to disgust. Their survey of 13,000 people supports this hypothesis. So how can we increase insect knowledge and reduce the amount of disgust? Education about invertebrates is an important first step, but overstepping bounds and making people feel insecure is not the way to go.

My use of the word bug is very deliberate. While all insects are not bugs, ‘bugs’ is often the term used to describe any small invertebrate we see in our homes and lawns. True bugs only include specific insects from the order Hemiptera (cicadas, aphids, and planthoppers to name a few). It also doesn’t include any other invertebrates like spiders or centipedes. I think it is important to use the term “bug” for insects and other invertebrates in conversation with people since that is the term they generally use for these animals. No one responds well to being told that they are wrong, and this is especially true when trying to talk about a subject most people prefer to avoid. Whether or not they use the right terminology is not the focus of this work; broad appreciation is. I wondered how to incorporate my years of experience and schooling in education, culture, and language with my love of bugs and art.

The last two years have led me on a journey of discovering how to positively engage those who live in urban environments with bugs. As luck would have it, I found two different ways that seem to start great discussions and may help shift our psyche: zines (small, self-published “books”) and popular culture. Art, insects, and popular culture have always been important to me, but I had never thought of combining them. These mediums allow us to talk about conservation in a manner that engages all audiences. I am not the first to implement these strategies, but I feel that they should be used more widely. By addressing disgust through creative methods like zines, and connecting bugs to already existing characters or cultural artefacts we can combat the disgust of insects.

Bugs in our lives

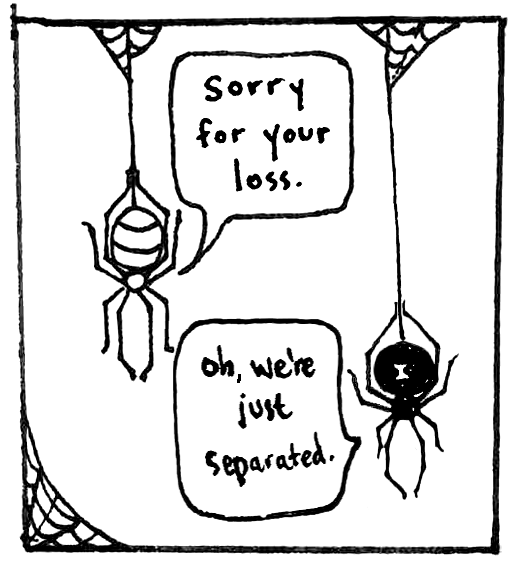

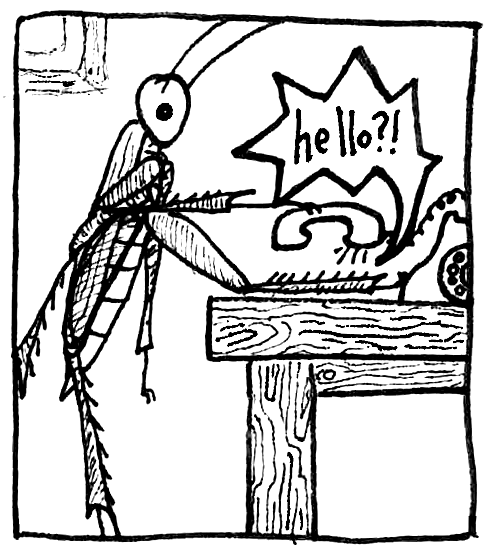

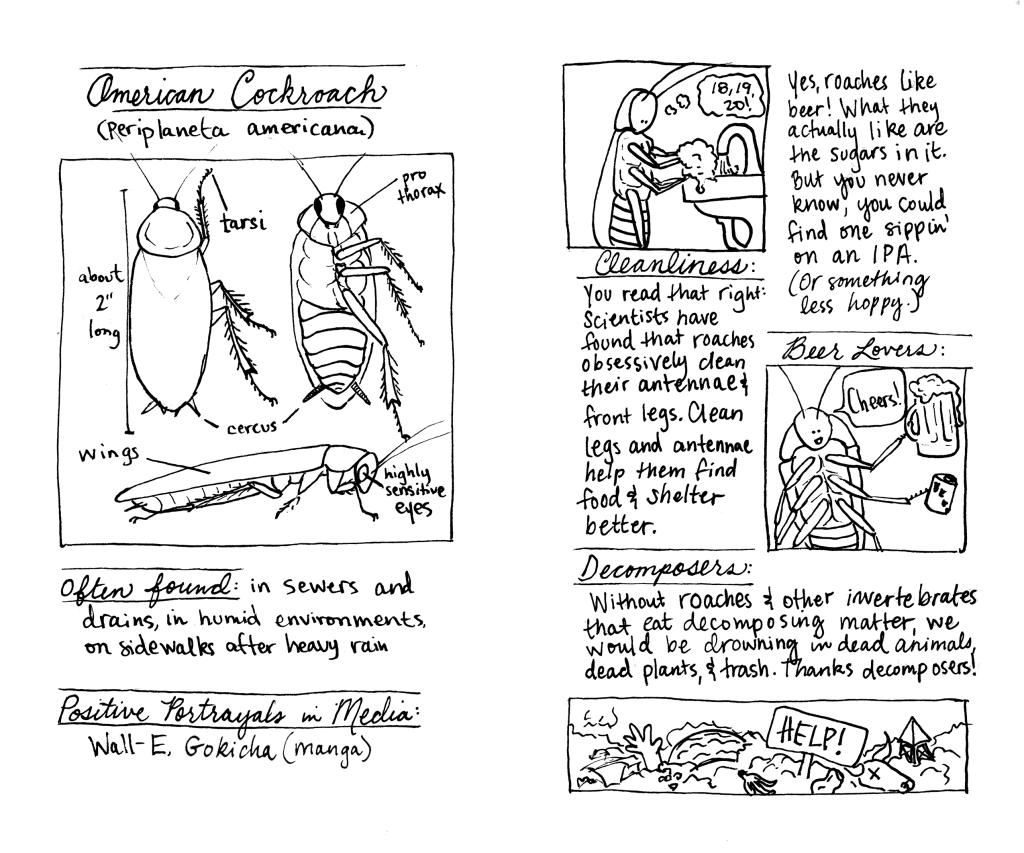

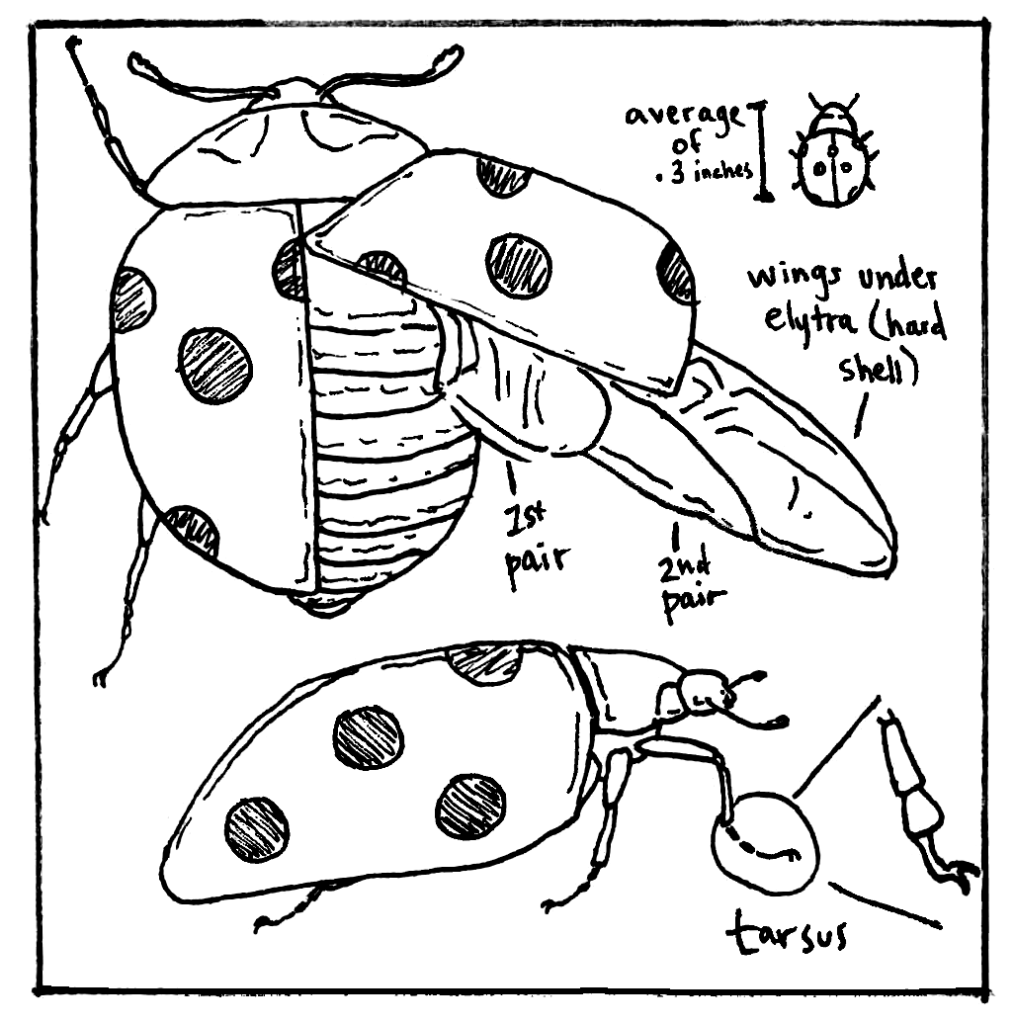

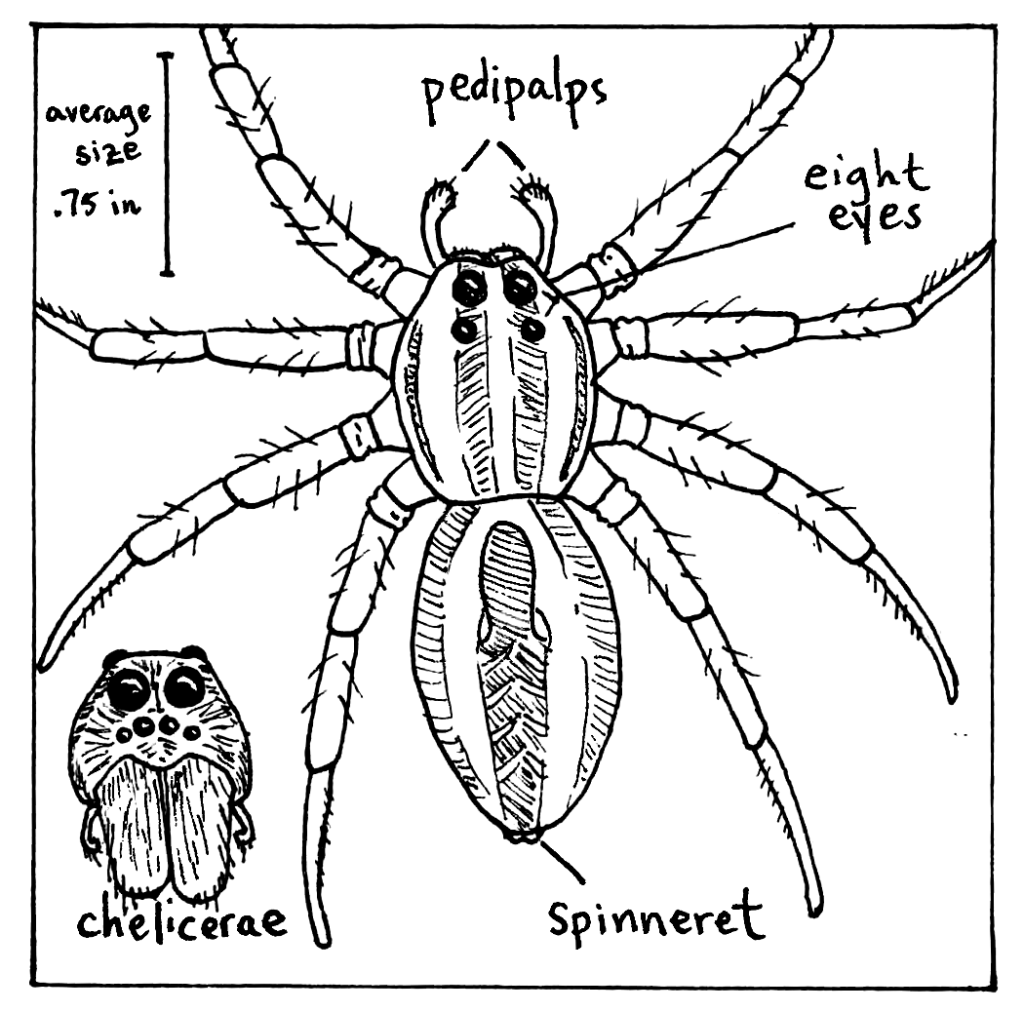

The first project I undertook was to create a zine to help people understand the importance and amazing traits of some common urban bugs—American cockroaches, house flies, wolf spiders, and so on—most of whom could show up in houses or apartments in the US. A small publisher took a chance on me because they could see my passion. The editor told me that they hated bugs but couldn’t stop reading my zine. People have said things like, “I loved learning about black widows! I’m not so scared of them anymore!”

Again, this is not new. Search for bug zines online and you will see that they are everywhere. Many conservation organisations have pamphlets available about insects, but they are often full of scientific jargon, look mass-produced, or contain overwhelming amounts of information. Pamphlets have their audience but there is also a sizeable market for small, accessible, handmade materials from conservation organisations. Zines are easy to make, cheap to produce, and allow people to talk about a subject in their own fashion. They are great for organisations, individuals, and classrooms alike. Zines give students ownership over the content and have been shown to create more engagement around their chosen topics.

My second approach was connecting insects with popular culture. Superheroes are more popular today than ever before and some of the most famous are named after invertebrates: Ant-Man, Spider-Man, The Wasp, etc. Taking this into consideration, I submitted a proposal to deliver a presentation at the Denver Fan Expo. There were over 100,000 people who attended the convention. One of the most common characters that both young and old attendees dressed up as was Spider-Man. In my presentation, I talked about superheroes and their real-life counterparts. While on stage in front of a massive crowd of people, I asked about the similarities and differences between Spider-Man and spiders. I had people in line for other booths yelling answers at me across the floor, parents and kids talking and drawing more “accurate” versions of some characters or creating an entirely new character. The interest and excitement was palpable, particularly among kids. It was an amazing experience that informed my next steps in using popular culture to engage a wider audience in the appreciation, or perhaps even conservation, of bugs, even if it meant shifting the needle of our perception of insects only slightly towards the positive end.

Research has shown us that people are not inclined to assist in conservation efforts just because we tell them there is a dire need for action. It is too overwhelming or too abstract or too distant to create a sense of urgency or make people feel like they can help in any way. Throughout my experiences over the last year, I have discovered ways to overcome those obstacles. While these projects don’t turn everyone into bug lovers, I am determined to try and in as many creative ways as I can. I know that I want to create and do more non-traditional insect conservation projects by tapping into what people already enjoy and showing them how it connects to the natural world. I hope to talk about how insects are woven into our culture and history, and allow for the ownership of ideas and accessibility of materials. I aim to develop unusual ways to communicate about insects that speak to people who may not typically care about these creatures.

I hope you will join me in the call to create love and appreciation around bugs in our lives.

Further Reading

Dunn, R. R., M. C. Gavin, M. C. Sanchez and J. N. Solomon. 2006. The pigeon paradox: dependence of global conservation on urban nature. Conservation biology 20(6): 1814–16.

Fukano, Y. and M. Soga. 2021. Why do so many modern people hate insects? The urbanization–disgust hypothesis. Science of the total environment 777: 146229.

Schmidt-Jeffris, R. A. and J. C. Nelson. 2018. Gotta catch’em all! Communicating entomology with Pokémon. American entomologist 64(3): 159–164.

Yang, A. 2010. Engaging participatory literacy through science zines. The American biology teacher 72(9): 573–577.