Feature image: A diver surveying a reef in decline.

Nowadays, data—especially big data—are a key factor in many decisions aimed at improving our lives. In healthcare, for instance, data is used to assess hospital readmission risk and improve outcomes for patients. Cities use data from connected devices like GPS to predict and prevent accidents and enhance public safety. All around us, data are being used to tailor solutions to tackle complex problems.

With continuing habitat loss and degradation of ecosystems globally, the need for data-driven solutions in conservation is at an all-time high. In response, governments have signed a global treaty—the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—to combat ecosystem loss and enhance resilience by 2050. Central to this agreement is the use of data to track progress toward the goals and targets set for each country.

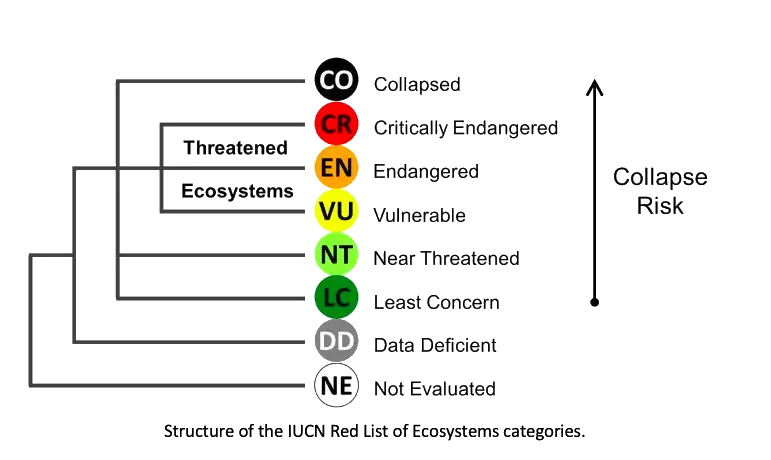

A key tool for supporting this effort is the Red List of Ecosystems (RLE). The RLE is a system through which data can be organised and used in a structured way to understand the status of ecosystems in relation to their proximity to collapse. Developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), this groundbreaking tool evaluates trends in the environment, ecology, and area and distribution of an ecosystem. It uses these trends to categorise ecosystems into various levels of risk: Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable.

Coral reefs are one of the most biodiverse and valuable ecosystems in the ocean. In many developing countries such as Kenya, they protect the coastline—including beaches, houses, and hotels—as well as provide habitats that sustain many seafood fisheries. However, they also experience challenges like mass coral bleaching, pollution, and overfishing which degrade their condition.

To assess the health of coral reefs in Kenya, researchers from CORDIO East Africa, the University of Melbourne, and other research institutions from Kenya applied the RLE framework. Their evaluation of 50 years of data collected from scientific dives and snorkeling surveys revealed alarming trends of ecological degradation across four components crucial to reef health: corals, algae (seaweed), and two fish groups—parrotfish and groupers.

The study concluded that Kenya’s coral reefs are Endangered, with more than half of surveyed reef sites experiencing significant declines in fish populations and coral cover. However, it is not all bad news—some reefs within zones where fishing is prohibited have higher fish populations, highlighting the positive impact of regulated fishing practices.

By identifying which aspects of Kenya’s coral reefs are most at risk, and where, this study exemplifies how data-driven assessments can provide crucial insights that local and national governments can use to plan ocean-related projects, protect marine areas, and pinpoint areas for restoration. In this way, assessments can help support nations achieve several targets set out in the Global Biodiversity Framework. However, it is clear that significant investment in the collection and sharing of ecosystem data is required to ensure that biodiversity conservation keeps pace with other sectors in making evidence-based decisions to safeguard nature.

Further Reading

Gudka, M., D. Obura, E. Treml, M. Samoilys, S. A. Aboud, K. E. Osuka, J. Mbugua et al. 2024. Leveraging the Red List of Ecosystems for action on coral reefs through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Conservation Science and Practice 6(12): e13255. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.13255.

This article was edited for submission by Timothy Allela, Communications Manager, CORDIO East Africa.