Can you imagine living in a world without roads? A world where we would be walking through thick forests or deserts, or hiking up and down mountains to arrive at our destination. Probably without realising it, we consider roads to be a part of the positive spaces in which we live. However, have you ever stopped to wonder what we lose when we pave new roads?

While roads connect various types of human settlements, they also form “linear infrastructure intrusions” through natural habitats such as forests, oceans and grasslands. Roads cut through forests forming fragmented patches of what was originally a contiguous natural habitat. This is very disorienting for animals, as roads often become barriers to movement of animals across the landscape. Herds and flocks are often separated by these divisions. For animals with home ranges larger than the given patch, this causes immense stress. They are forced to find all their resources, including food, shelter, and mates, within the smaller area they are left with, thereby exhausting resources, causing inbreeding and the faster spread of diseases. This fate has befallen several animal species that are rare and endemic to certain areas, such as orangutans, which are only found in Borneo and Sumatra. As humans rapidly “develop the land” we run the risk of further boxing orangutans into smaller habitats, ensuring their extinction.

Roads cutting through forests or other terrestrial landscapes are a major cause of animal mortality worldwide. Vehicular collisions with crossing animals are extremely commonplace on highways surrounded by natural landscapes or on smooth roads, where traffic drives at extremely high speeds.

Most of you would have encountered an animal crossing in front of your car, and you may or not have been able to stop, depending on the speed and situation. While conducting research for my masters’ thesis in Madagascar, a biodiverse island along the eastern coast of South Africa, I often found snakes and chameleons crossing the roads. Sometimes I found the snakes near urban areas on heavy traffic roads, while at other times they jumped or slithered away quickly on dirt roads in rural remote areas. So, I have personally encountered situations where I was able to successfully slow down or go around the animal and save them without disrupting traffic or landing in an accident. This was mostly thanks to the island having very less vehicular traffic in most areas and dirt roads in other areas. But I have also had the experience of applying the brakes very suddenly on a smooth single-lane highway to save a bird and its chicks crossing the road, naturally followed by my dad shouting at me, and lots of angry honking from the cars behind me (I am a wildlife ecologist, couldn’t help it!).

In the time after my bachelor’s degree, I was in Coorg, Karnataka, volunteering with the Western Ghats Nature Foundation—an NGO working on wildlife conservation. Considering my love for reptiles, when

I heard from a friend about multiple dead snakes on an interstate highway connecting Karnataka and Kerala, I just had to go and see for myself to get numbers and species names. The highway had been recently renovated at the time of the study and was lined by forested areas on both sides. It cut through

the Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Ghats, which is recognised as a global biodiversity hotspot. I would wake up early every day and ask one of my friends from the NGO to take me as a pillion on his bike to this highway stretch. We would let the bike crawl at the speed of a snail and I would scan the road for any dead animals. In a period of just eight days, I found a total of 117 road killed animals on a roughly 18 km stretch of the highway. You won’t believe it, more than 60 (!!) of these were reptiles! This number was the highest amongst all the animal groups I found roadkill for, including amphibians, reptiles, insects and mammals. If lizards and snakes are to be counted separately within reptiles, snakes had higher incidences of mortality than lizards (I have a particular soft corner for snakes, so definitely not good news!). What made it worse was that I found so many beautiful snake species that I had not had the chance to see to date in the wild. Many of these species, such as the hump-nosed viper, the Malabar pit viper, and the Travancore wolf snake are also endemic to the Western Ghats. Being a herpetologist–a person who studies reptiles and amphibians–this was particularly heartbreaking.

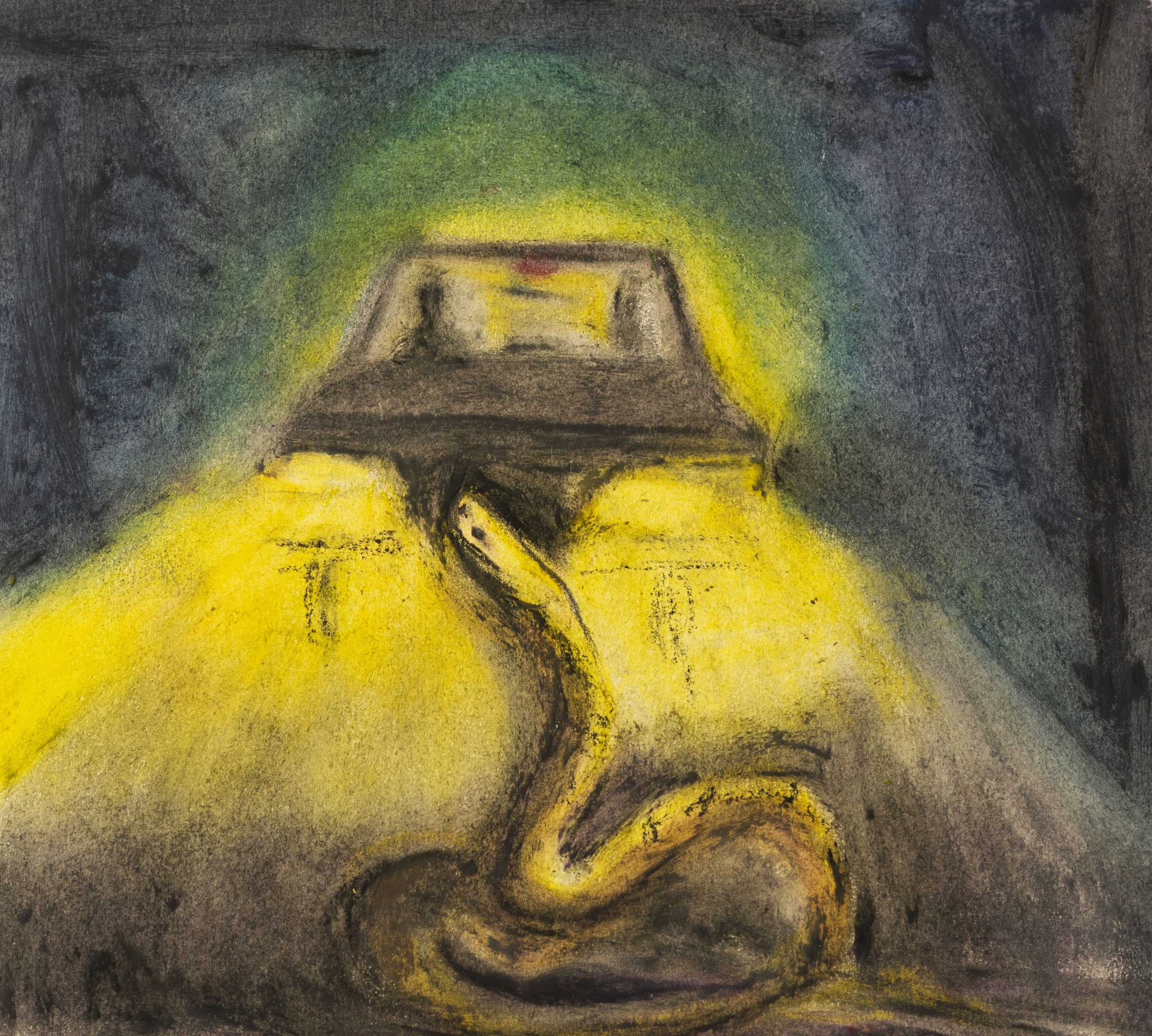

Reptiles often cross roads to go from one patch to the other, but they can also be found simply sitting on the roads (Really, what joy is found in doing this?). They are cold-blooded animals who regulate their body temperature by behavioural means. They take shelter in shaded areas when their body heats up and come out in the sun when their body gets too cold. Certain areas, such as rocks or tar roads, are particularly beneficial for them to gain heat (basking in the sun). These surfaces heat up quicker in the day time as compared to the surrounding areas and lose heat slower than their surroundings at night. So, it is possible to find a snake coiled and chilling (actually trying to get warm) right in the middle of the road where the canopy of the forest does not obstruct the sun’s light. I did find a dead snake in exactly that position! It was a beautiful coral snake with a shiny black and red body, a rare one to encounter when you go looking in the forest. But I hope you might now understand why reptiles are particularly at risk of being run over by vehicles on the road. To add to this, there is the problem of their small size, which might render them invisible to vehicles moving at high speeds. And in India, snakes in particular are frowned upon. People often go out of their way to run one over if they see it crossing the road. It is sad, but true. That snake did no harm to anyone and was probably on its way to find a nice chick to hang out with. Alas!

Setting my sadness aside, I mapped out whatever data I had collected and located hotspots on that 18 km stretch of the highway, where more than one snake roadkill was found. I did this because I thought there may be some places with higher probability of snakes crossing the roads. And if we can do something at those locations to prevent roadkills, it would make some difference to these creatures at least. There are several solutions to such animal road mortalities. Some of the simplest ones include introducing speed limits and speed breakers, which allow the driver to slow down in time and may also allow animals to escape; reduction in traffic volume by regulating the number of vehicles allowed each day, especially during festivals and holidays; and temporary closure of roads, such as at night, when a majority of snake species are active, or during the breeding season of vulnerable species when their activity may be higher. Other mitigation measures for reptile roadkills include the construction of underpasses or culverts (underground pipes) along with fences. The fences can help prevent the animals from crossing the roads and direct their movement towards the underpasses or culverts, where they can cross safely. We could also place metal boards on the sides of roads which would heat up like the roads, and may be encountered and preferred by reptiles for basking, before they come onto the road.

Apart from reptiles, I found several other dead animals, including monkeys, during the survey. I suspect that the primary cause of higher mammal deaths is the irresponsible behaviour of people passing through the area, who were often observed stopping by to feed troops of monkeys. Such easy access to food would naturally bring the monkeys closer to the roads more often. Unfortunately, this may be particularly prevalent due to the mythological association of monkeys with the Hindu god Hanuman. A simple way to resolve this issue would be to ban the stopping of cars along this forested stretch of the highway, which would require more regular patrolling by the forest department or the local police, both of which have offices nearby.

Most animal roadkill mitigation measures do not require too much effort or monetary funds, and can be introduced before, during, or after road construction. It is our responsibility to at least provide animals safe passage within their natural habitats. Further studies could better inform our decisions pertaining to suitable mitigation measures. Hence, many conservation organisations have come up with phone applications–for example, ‘Roadkills’ and ‘Road Watch’–which let you record roadkills.

So the next time you’re on the road, I hope you have one of these apps on your phone, avoid overspeeding, keep an eye out for wild animals while crossing green areas, and record any roadkills you encounter so that scientists and wildlife conservationists can use the data to save some animals, if not all, from extinction.

P.S. This might also help you see some animals that you may never see during the wildlife safaris you pay heavily for. I once saw an aardwolf (go Google!) while driving on the road in South Africa and trust me, it is one of my most cherished sightings ever!

(Right: Illustration of the process of transformation of natural landscapes due to deforestation and clearing for development of linear infrastructure such as roads)

Further reading

Bansal, U. 2020. A study of reptile road mortalities on an inter-state highway in the Western Ghats, India and suggestion of suitable mitigation measures. Captive and Field Herpetology, 4.

Glista, D.J., DeVault, T.L., DeWoody, J.A. (2009). A review of mitigation measures for reducing wildlife mortality on roadways. Landscape and urban planning, 91, 1–7.

Trombulak, S.C., Frissell, C.A. (2000) Review of ecological effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatic communities. Conservation biology, 14, 18–30.