Most of us don’t think about the ways we can connect the imagery of climate change— factories pumping thick smokestacks, inundated coastlines and destroyed homes, polar bears sinking on melting icebergs—to the thing we need most every morning: a cup of coffee. But its agriculture, production, and consumption all play an intimate and unstudied role in tackling the largest environmental crisis of our era.

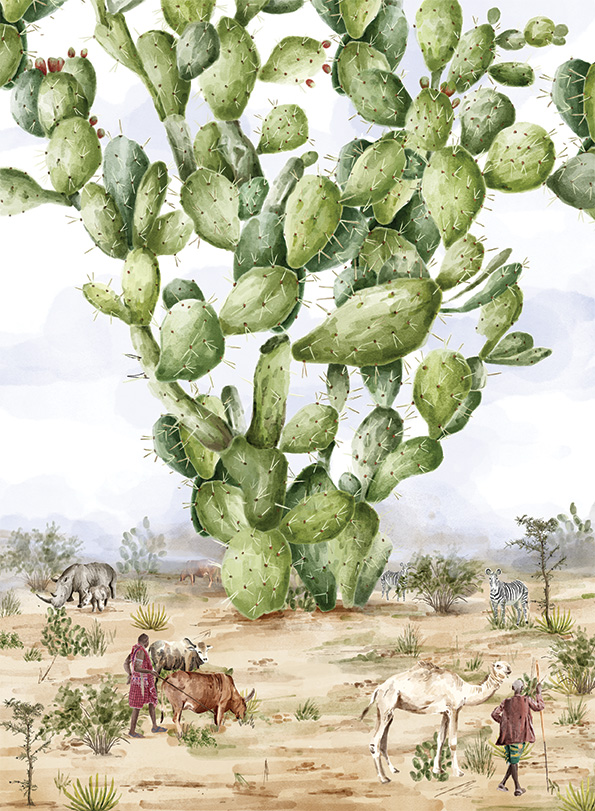

Recently, an academic study published in Bioscience found that while coffee cultivation in Asia is on the rise, shade-grown coffee systems have decreased by 20 percent globally since the 1990s. As climate change increasingly threatens future outputs of one of the most important beverages to modern society (after water, of course), this matters for a whole slew of reasons. Open-sun cultivation, often pictured as rows and rows of manicured coffee bushes devoid of any other crop varieties or native vegetation, remains the dominant mode of cultivation today. But trees contribute more than just shade to the coffee, adding to its unique texture and flavor profiles across hilly landscapes throughout the Western Ghats. The diverse canopies of native trees contribute incredible species diversity, offering additional habitats to the fauna that call it home. They offer strength in numbers, providing resilience against natural shocks to the ecosystem like flooding, droughts, and wildfires. They filter and clean the water, maintain soil quality from erosion, and most importantly in the era of global warming: they store carbon.

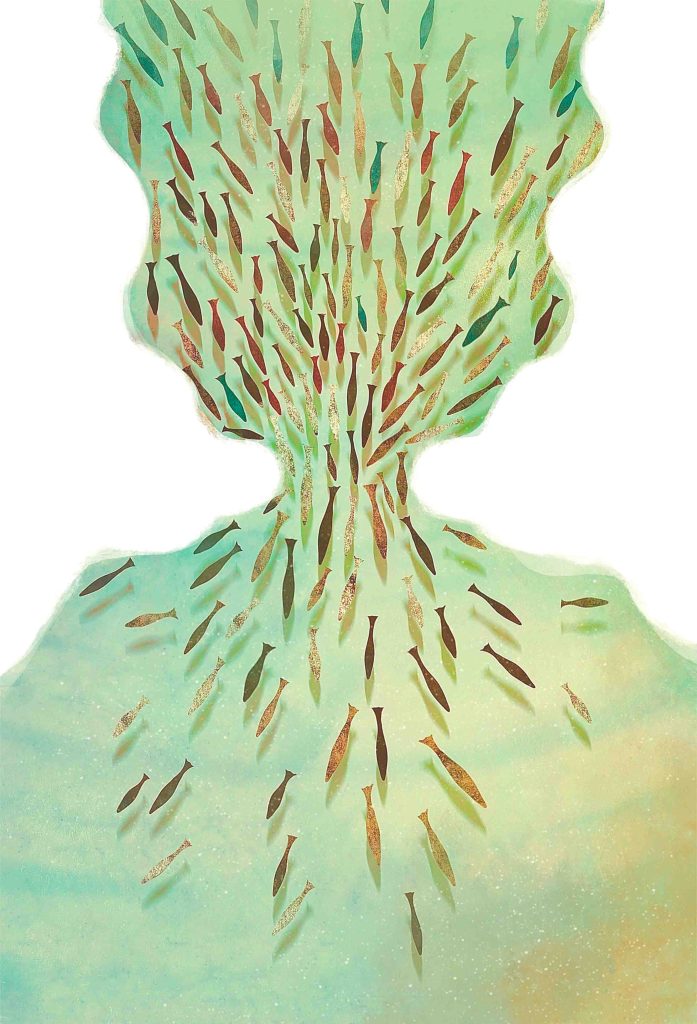

India remains unique in the world as most coffee grown here is often in diverse multi- cropping homesteads under the canopy of forest trees, which play a huge role in mitigating the amount of CO2 being pumped out by our factories, cars, and power-plants. The process works a little like this: through photosynthesis, the trees take in CO2 and exchange it for the oxygen we need to breathe. But this also does something else, something we can’t see with our own eyes. The carbon gets fixed by the trees, sucked up through the dense network of leaves, woody stems, and thick trunks back down into earth where it is stored as soil carbon. This ancient process becomes one of the most important “sinks” in the carbon cycle, making trees the real unsung heroes of climate change. As natural agents in mitigating the spiraling levels of greenhouse gases around the world, we need them to get the job done.

That’s why promoting shade-grown coffee is such a big deal. This lies at the heart of some of the research I have been conducting with Black Blaza as a Fulbright researcher alongside the Bangalore-based institute Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE). Black Baza prides itself on being an activist company with a unique mission: to reconstruct the existing marketplaces for coffee and re-embed it in place, people, and ecology. This means eliminating the use of pesticides or fertilizers, and relying only on organic, natural farming. They envision a market system which values producers and nature equally by conserving native forest cover and local biodiversity (like the small raptor that inspired the company’s name) while enhancing the participation, voices, and ideas of farmers in the overall production cycle.

The focus of their efforts lies in the hazy green mountains of the BR Hills tiger reserve, the mighty ecological corridor between the Western and Eastern Ghats that’s home to hundreds of different species of wildlife. It’s also the home of the Soliga community, the Adivasi stewards of the land who have been intimately linked with these forests for hundreds of years. Originally the community lived off the forest, harvesting non-timber products like lichen, gooseberry, and honey while sometimes practicing shifting cultivation. But once the region was recognized as a Wildlife Sanctuary in 1974, the Soliga community was directed to settle in hamlets outside of the forest interior and practice settled agriculture. Families started growing traditional crops—millet, ragi—which quickly attracted hungry wildlife like elephants, boars, and deer, disrupting the delicate balance between conservation and livelihoods. In the 1990s, the government promoted coffee as an alternative cash crop that didn’t cause human-wildlife conflict and was easy to maintain, and family by family, households converted to its cultivation. Since they live in highly protected forests, the farmers often kept native trees standing, planting coffee by the bush on the forest floor. So while the Soligas never actively made the decision to grow coffee in this landscape themselves, year after year it becomes a bigger part of the community’s new ecological identity.

But even now, there are many unanswered questions in this new forest-agriculture landscape. In a rich biodiversity hotspot like BR Hills, how was the presence of coffee farms affecting the connectivity of key forest species like pollinators, or the diversity profile of standing trees? Black Baza knew they couldn’t effectively reach their radical mission without the right metrics. Circling back to the mighty power of carbon storage, the untapped potential of shade trees as an ecosystem service had also remained unstudied and unnoticed.

That’s where we came in. My team arrived at the tiger reserve at the tail end of the monsoon season with a deceivingly difficult mission: we wanted to know just how much carbon was being sequestered, or stored, in the farms that Black Baza partners with in BR Hills, compared to the neighboring forests. Farm after farm, we set up plots, delicately wrapping tape measures around trunks, counting the centimeters across the branches of coffee bushes, and identifying the diverse native trees by their local name. We machete’d our way through forests choked by the Lantana vine, an invasive plant introduced by the British during their colonial occupation. While the Brits left, the Lantana unfortunately stayed, and still today no natural source of control exists for this weed. We passed by mounds of fresh elephant dung, a reminder of their ever-close proximity. The Soliga rule of thumb: if you see a wild elephant, run. After months of field work, we had the measurements we needed to understand the power of shade coffee as a fighting force for climate change. And what we found was pretty wild— the carbon stored above ground in shade coffee systems was near-equal to forests plots of the same size, meaning the two systems were comparable in storing carbon within the vegetation’s woody tissue. But this is not to say that shade coffee systems are the same as native forests. Just because they may provide similar carbon storage benefits doesn’t mean we should replace every protected forest with coffee farms. But for coffee production itself, this really exhibits the mighty ecological power trees actively offer us when we grow coffee under their leafy canopies. And for Black Baza, this helps them get one step closer to reimagining the role coffee can play in conservation and agricultural livelihoods. So the next time you pour a cup of organic shade-grown brew, know that you’re not just enjoying the delicate tastes of the elevations at which it grows, or its chemical-free inputs—you’re giving a nod to the original actors keeping our planet cooler, healthier, and greenhouse gas-free.

After months of field work, we had the measurements we needed to understand the power of shade coffee as a fighting force for climate change. And what we found was pretty wild— the carbon stored above ground in shade coffee systems was near-equal to forests plots of the same size, meaning the two systems were comparable in storing carbon within the vegetation’s woody tissue. But this is not to say that shade coffee systems are the same as native forests. Just because they may provide similar carbon storage benefits doesn’t mean we should replace every protected forest with coffee farms. But for coffee production itself, this really exhibits the mighty ecological power trees actively offer us when we grow coffee under their leafy canopies. And for Black Baza, this helps them get one step closer to reimagining the role coffee can play in conservation and agricultural livelihoods. So the next time you pour a cup of organic shade-grown brew, know that you’re not just enjoying the delicate tastes of the elevations at which it grows, or its chemical-free inputs—you’re giving a nod to the original actors keeping our planet cooler, healthier, and greenhouse gas-free.