Conservation is at a critical juncture, as many acknowledge the need for a new paradigm that centres collaboration with living systems. And this new paradigm is increasingly recognising the role of fungi in shaping our world.

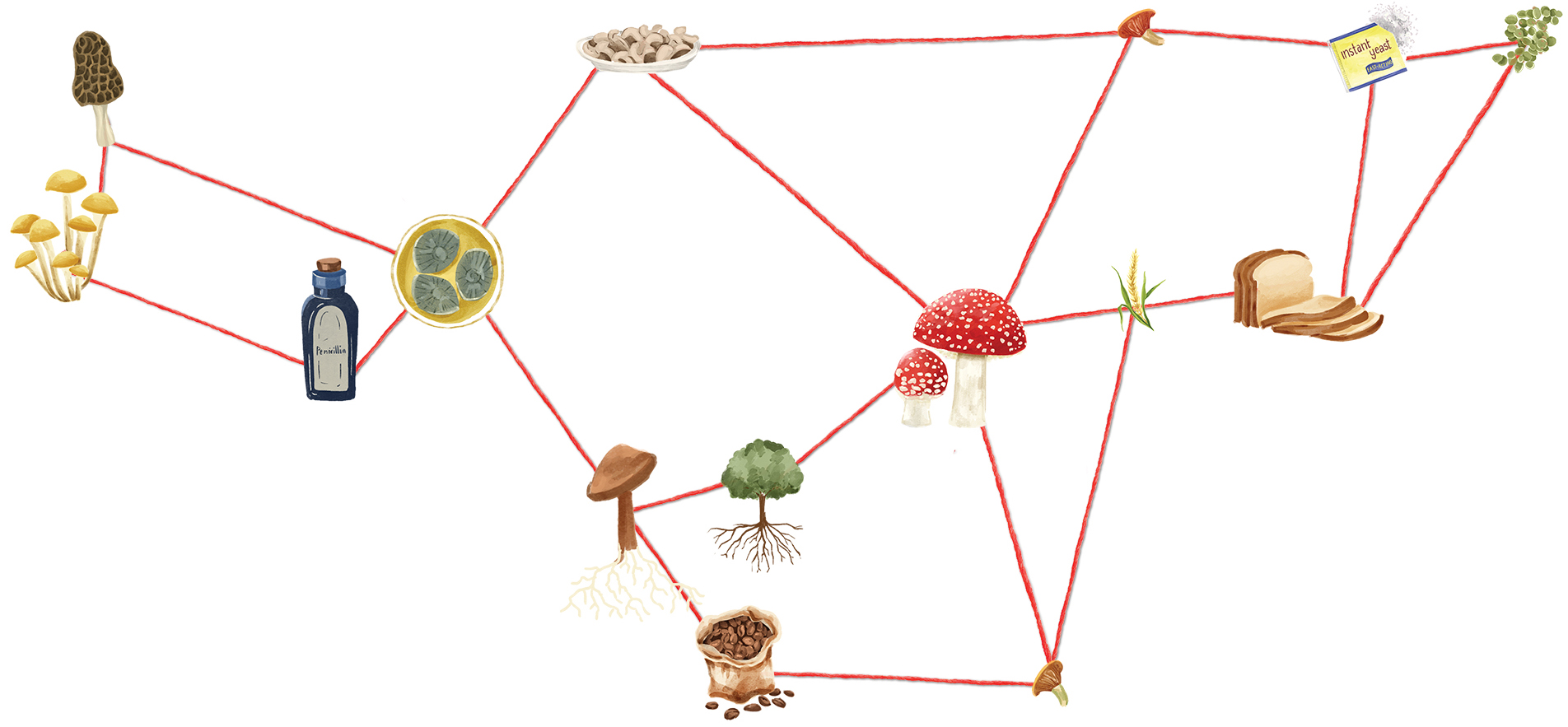

Fungi are the second most diverse group of species after insects, with an estimated total of 2.5 million species across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine environments. Fungi underpin all life on Earth, playing important roles in nutrient-carbon cycling, decomposition, and regeneration. Most plants depend on fungi for survival, and many animals rely on them for food and water. Fungi are also crucial for our food security, livelihoods, and the economy, supporting multi-billion dollar industries in edible mushrooms, antibiotics, biofuels, and even plastics and building materials. Coffee, bread, chocolate, and penicillin would not exist without fungi!

How can we leverage the power of fungi for effective change at the policy level? First, we need to understand where these organisms live. The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) is one of various organisations and initiatives focusing on the collection, monitoring, and conservation of soil microbial communities. Other initiatives include the African Microbiome Initiative, the Australian Microbiome Initiative, the China Soil Microbiome Initiative, SoilBON, the European LUCAS soil survey, the Earth Microbiome Project, the Global Soil Mycobiome consortium, and GlobalFungi.

This work, leveraged with a growing body of scholarship on fungal conservation science and social science, can make important contributions to a range of international policies and initiatives. Here we present an overview of a possible first set of interventions.

Fungi in the spotlight

Historically, fungi have been overlooked in climate solutions, biodiversity assessments, and conservation targets due to a lack of data and expertise, as well as a misunderstanding that they were plants rather than an independent kingdom with unique chemical and physical attributes. Fungal conservation efforts began slowly in the 1980s and 1990s with initial research on the impact of air pollution on mycorrhizal species (which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots) in Europe, the impact of deforestation on fungi in the northwestern US, and organisations being formed in Cuba and within the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The 2000s saw a more rapid change, with expansion to five IUCN specialist groups in 2005 and the Declaration of Cordoba in 2007, calling for effective conservation and sustainable use of fungi. Since 2015, there has been a significant increase in efforts to evaluate the extinction risk of fungal species through the Global Fungal Red List Initiative. Supported by the IUCN, newer organisations such as Fungi Foundation have called for an increased recognition of fungi as one of the three kingdoms of life critical for conservation (see Flora, Fauna, Funga initiative). As a consequence of this campaign, in 2024 the National Geographic Society even changed its definition of ‘wildlife’ to include fungi.

Nature-based solutions

With many fungal species at high risk of extinction due to habitat loss, climate change, and pollution, urgent recovery action, restoration, and protection of fungi are needed. Because of their intrinsic relationships with plants, animals, and humans, protecting fungi offers a wide variety of nature-based solutions to support plants, ecosystems, and human communities. There are a host of international agreements and programmes whose goals will be enhanced and better met by taking these points into consideration, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

Protecting and ensuring the sustainable harvesting of wild edible and medicinal fungi will contribute to the protection of biodiversity as suggested by the CBD, and to SDGs related to combating world hunger, providing work and economic security through responsible means, and managing nature in ways that benefit nature and people. Furthermore, mushroom hunting is often an important source of income for women in rural communities. Thus, ensuring the sustainable and equitable use of fungi also promotes gender equality, an important goal for the SDGs and the UNCCD.

Fungi can also be integrated as a nature-based solution to prevent and mitigate some threats related to climate change, farming, and pollution. More than 90 percent of plants—including trees and food crops—have mycorrhizal fungi associated with their roots through symbiotic relationships. This particular group of fungi helps plants efficiently absorb nitrogen, phosphorus, and other critical nutrients, while drawing carbon down into the soil. Mycorrhizae also improve plants’ capacity to absorb water from the soil and their resilience to drought. Soils store 75 percent of terrestrial carbon, and mycorrhizal fungi play a crucial role in keeping that carbon in the ground, which helps regulate the Earth’s climate—an important part of all the international agreements mentioned above. These fungi also support crop resilience against pests and diseases, and maintain soil health and stability.

Like combating climate change, responsible agricultural production and land management are also addressed within the SDGs, CBD, and UNCCD. While acknowledging that fungi are a major source of crop diseases and some are becoming invasive, SPUN believes their careful integration in sustainable farming can support larger crop yields and more nutritious foods, making them an indispensable tool to help us meet important aims related to food security and responsible production. Thoughtfully incorporating mycorrhizal fungi in agriculture can also reduce the need for fertilisers and pest control chemicals, consequently reducing pollution from runoff and improving water quality.

Protecting underground networks

A key priority for SPUN is identifying hotspots of diversity and endemism of mycorrhizal fungi to inform effective spatial planning, management, and protection, and to map the contribution of these fungi to carbon drawdown and climate mitigation. Additionally, SPUN has been partnering with other organisations, such as The Nature Conservancy, to implement more effective, evidence-based restoration and management practices, and priorities informed by data on mycorrhizal fungi diversity.

SPUN participates in international meetings, such as the recent 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. It’s also part of a group of experts leading the development of a Global Strategy for Fungal Conservation that closely aligns conservation and research strategies with the CBD Global Biodiversity Framework targets. This strategy will support mycologists, conservation practitioners, decisionmakers, and governments in integrating fungi into the implementation of the CBD targets.

At the core of SPUN is a network of external collaborators sampling mycorrhizal fungi worldwide as part of our Underground Explorers Program. This granting programme is designed to fuel high-quality mycorrhizal research from understudied regions around the world by providing funding, access to innovative technology, and knowledge sharing with local researchers. SPUN strives for open access to our data and knowledge products, while also ensuring prior consent and proper attribution to Indigenous peoples and local communities, for example through the use of “Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels” produced by the organisation Local Contexts.

We hope SPUN’s work can be an example of what can and should be done to integrate fungi into conservation policy and action, inspiring others to follow and effectively conserve all species on Earth.

Further Reading

FFF initiative. 2025. Flora, Fauna, Funga. https://faunaflorafunga.org/.

Fungal Conservation Network. 2024. Contribution of fungi to the Global Biodiversity Framework. https://zenodo.org/records/14680634.

Hawkins, H. J., R. I. Cargill, M. E. Van Nuland, S. C. Hagen, K. J. Field, M. Sheldrake, N. A. Soudzilovskaia and E. T. Kiers. 2023. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Current Biology 33(11): R560-573.