Two become one

I’m an artist inspired by nature in my free time and a professional outdoor education specialist teaching about the natural resources in Nebraska, U.S.A, during my workday. Yet, art and science communication had been kept separate in my life. Both personally and professionally, I felt a pull to share my love of the natural world in hopes of inspiring others to love it too, but these things were always done independently. Looking back now, it seems a little crazy that it took a global pandemic to make me pause, to spur my creativity, and to bring art and science together. But ever since March 2020—when the COVID-19 pandemic struck—everything has become a little clearer.

There is a definite need for scientific information and art to be joined together to effectively communicate and interpret the value of our local natural resources.

From the water that sustains life, to the ecosystem services that habitats like wetlands provide, an understanding of our planet and natural resources is essential to tackling big issues like climate change and habitat loss. For many, if we don’t see something, it simply doesn’t exist. Art might just be the key to helping every person, even those who don’t “like” science, to understand their role in the bigger picture.

I know, I know—this seems like a weird conclusion to come to in the middle of a worldwide crisis. But I was an outdoor educator who suddenly couldn’t take kids on hikes to explore the natural world because everyone was locked down inside their homes. I was also an artist who couldn’t stand the idea of wallowing when I could contribute something good. So, one day as I sat at the kitchen table thinking about what I could actually control, art and science became one, and as a result, the two once-separate parts of my life merged into a unified whole.

The relationship between art and science

It’s not new, but the relationship between art and science has certainly ebbed and flowed through time. Initially, many scientists were simultaneously artists, using drawings and paintings to document their discoveries.

Leonardo da Vinci, John James Audubon, Maria Sibylla Merian, and several others contributed much of what is known about the natural world using visual art. Somewhere along the way, science and art took different roads. Though these roads crossed at times, for a while it seemed that the old connection was not as foundational as it once was. Recently, scientists and artists have begun working together more intentionally, but it can look different depending on the desired outcome. Sometimes it’s just to illustrate something like a microscopic cell for a scientific textbook, while at other times, it can be a large mural in a children’s museum. Art can help explain complicated scientific concepts and globally relevant information, but how often is it used to specifically connect people to the natural resources around them?

A personal twist

My passion lies in teaching people of all ages about their everyday ecosystems and the species they can find in their own backyard here in Nebraska. Some may argue that there should be a greater focus on endangered or threatened species because they are more important, and maybe this is true in some sense. But, we cannot expect for someone to go from zero experience in the outdoors to a 100 percent fully invested, conservation-minded decision-maker with nothing to help get them there. We can begin this journey by connecting people to their own natural surroundings and the living beings found there, and this process takes time.

When I led hikes at a nature centre, I would ask students what they thought we would see on our hike. The most common answers? Bears, if we were in the forest, or alligators, if we were in the wetlands. All this was in Eastern Nebraska along the Missouri River—a wooded habitat where the largest animal you might find is a white-tailed deer, and on the absolute rarest of occasions, a mountain lion passing through. This experience showcased the great disconnect between young people and their own local ecosystems, and similar knowledge gaps exist for adults too. If we don’t take the time to understand where our audience is at and meet them there, we cannot expect them to take positive conservation action or change their behaviour. We need to start simple. I propose that art is the key to building that connection—particularly art featuring local species.

At the height of the pandemic, I created a piece of artwork that combined my love for educating people about local nature with a drawing inspired by what I saw outdoors. I called it “Grace’s Guide to the Outside”, and I first shared it on social media. The feedback I received from my science and non-science friends alike was overwhelming!

No matter their background, people reached out to say they loved it, and even the city’s largest paper wanted to do an article on it. And so, I continued to create them. The evidence that told me that my art was sparking a real connection to the natural world (as I had hoped it would) was when I created one about cicadas. Someone whom I didn’t know that well commented on the artwork and said, “I’ve seen those shells on our garage door. Didn’t know they were cicadas!” This comment validated the fact that my art and this information had value in the way it was presented. Someone learned something new and could now connect better to a cicada shell the next time they ran into one. They also have two young children whom they could now teach about this insect that is so often seen in the midwestern United States.

The need for a native focus

Recent studies have pointed out just how important it can be to use art when learning about scientific topics. While the process can take time and cost money, the power of effective graphics has proven to be extremely valuable, especially as media avenues for sharing research continue to change. For those in the scientific community, we must begin to ask how we might share our knowledge with others who might not have the same background. Not only this, but for those that care about our world’s biodiversity, it’s time to pause and think about how to get people to care about conservation.

Thinking through what exactly conservation even is and how you would explain it is something to consider. Even as students are taken on a simple nature excursion around their school, there is evidence pointing to the need for their teachers to have some baseline knowledge of the local species they might encounter to spur on the student’s interest. Elephants and rhinos are certainly eye-catching, but what can a child from the midwestern United States do to help them? We have to start much smaller. A pill bug crawling across the sidewalk. Red-winged blackbirds flocking across the sky in the spring. A fox running through the city park. First and foremost, people need to be awake to what is happening around them. Emotional connections are a key piece of humanity and art is great at evoking that initial flicker of interest.

Get out there!

From the moment we set foot outside, there are opportunities to learn about conservation, even if we don’t have a scientific background. I propose that we start simple. Through observation and art, there are many chances to connect to local species. Whether you take a walk in a city park or head into the field for research, there is potential for an increased understanding of the environment around you. If you’re an artist (or even if you don’t consider yourself one) try drawing or painting what you see during time spent outdoors. Learn more about native species in order to better understand them and how you might impact them.

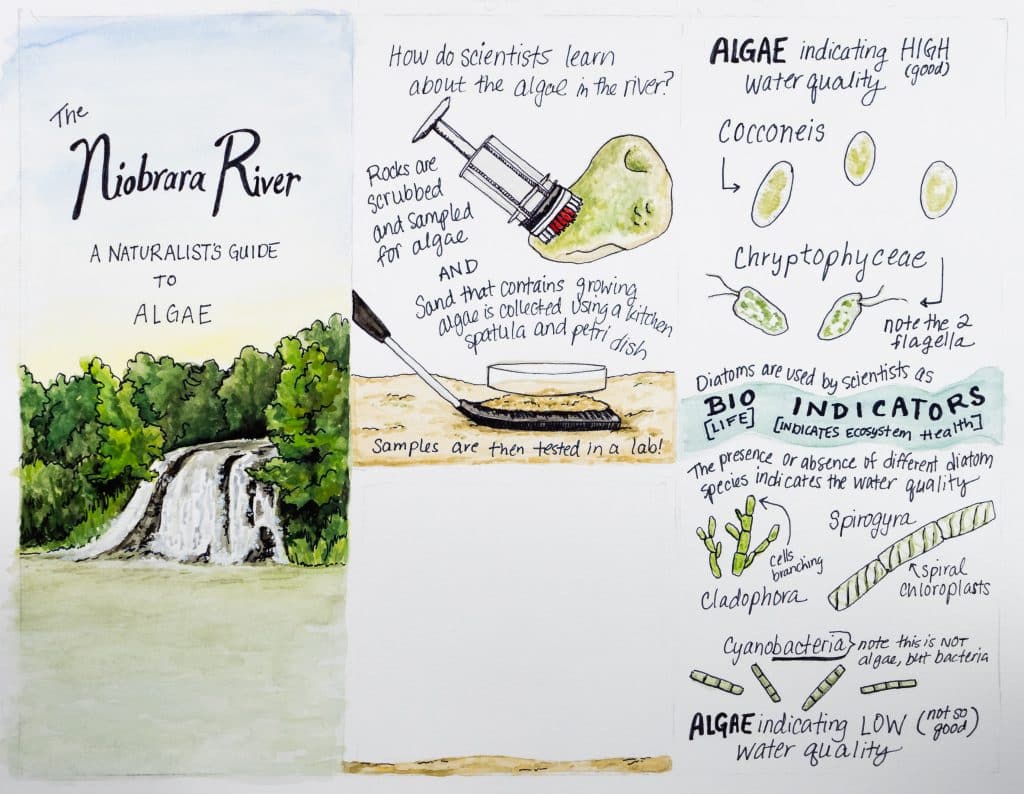

I myself have been working alongside a professor from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to create artwork representing her research on the aquatic macroinvertebrates (such as crayfish) and algal communities found in the Niobrara River in Nebraska. We are creating two brochures that will educate people using the river, which includes tubers, kayakers, and canoers. I bring my artistic skill to the project and expertise in communicating her scientific information in a way that is easy to understand, while she brings content expertise. It’s an exciting partnership!

If you possess a stronger interest in science, think about how your work could be interpreted into an artistic representation with local ties that can prompt a relatable experience for your audience. Most of all, keep in mind that when you better understand and empathise with your local natural resources, you’re more likely to know how to positively interact with them. With art to tie it all together, you might just encourage people down the road to an even bigger positive impact on the world around them!

Further reading

Khoury, C. K., Y. Kisel, M. Kantar, E. Barber, V. Ricciardi, C. Klirs, L. Kucera et al. 2019. Science–graphic art partnerships to increase research impact. Communications Biology 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0516-1

Skarstein, T. H. and F. Skarstein. 2020. Curious children and knowledgeable adults – early childhood student-teachers’ species identification skills and their views on the importance of species knowledge, International Journal of Science Education 42(2): 310–328, DOI: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1710782

Zaelzer, C. 2020. The value in science-art partnerships for science

education and science communication. ENEURO Commentary 7(4): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0238-20.2020