DIMINISHED NATURAL ORCHESTRAS ARE A HIDDEN DIMENSION OF BIODIVERSITY LOSS

Deep in the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh, where the mighty Siang river carves its way through the Himalayas, nestled the Adi hamlet of Tuting, amid overgrown green fields, verdant mountains and the river, itself deep green. The very moonlight seemed green as it shone on the ghostly mist rising from the gorge. Nineteen years ago, a search for India’s last takin-that strange-looking, mysterious cousin of the musk-oxen-had led me (and colleagues from Wildlife Institute of India) to this remote village, amid dense rainforests that we’d only read about, us kids of the concrete jungle. We were wide-eyed with wonder.

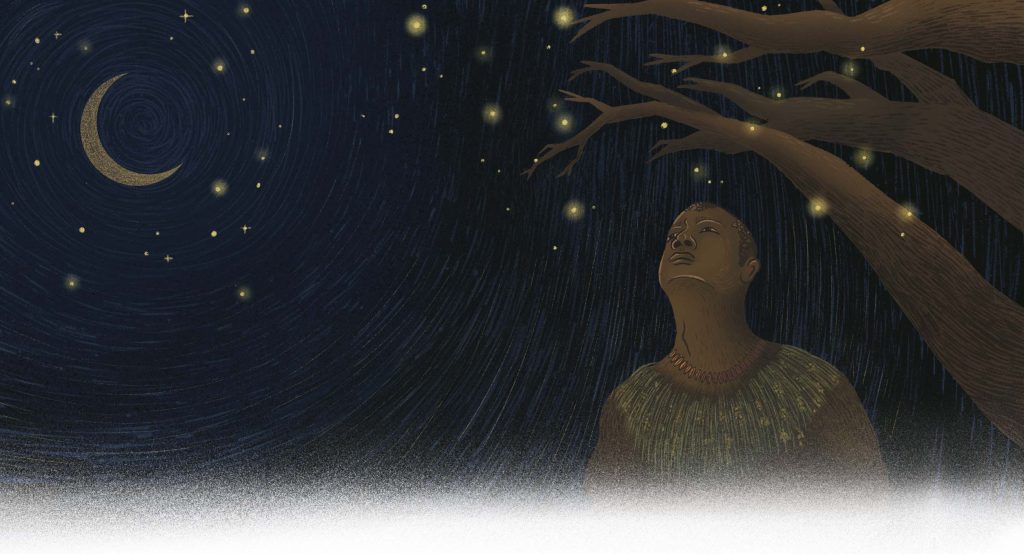

Talom Yaying, an Adi hunter from Tuting, took us to look for takin in the mountains where he hunted regularly. He offered us his cave for the night, in the heart of the rainforest, high up on a ridge overlooking the great gorge. Such wonderful, magical country-and so hopeless my attempts to capture its rapturous beauty on a few frames of celluloid. Put that camera away!

On our way back, Talom told me he felt compelled to spend some nights every week in his cave-away from home and family. For in the village, the only sounds to awaken him at dawn were chicken, dogs and pigs. But up in his cave, he was serenaded by the songs of wild birds and animals! Even in Tuting, a village completely surrounded by rainforest, he missed the sounds of the forest! Unlike us city-bred wildlifers, he knew exactly what he missed and where to find it. Growing up amid the steady din of city life, most of us don’t even recognise those natural sounds the warbling of birds, croaking of frogs, chirrupping of crickets. How, then, can we hope to recover what we don’t even know we’ve lost?

Years later (many spent studying songbirds in wild and human habitats) I share Talom’s sense of loss more keenly as I contemplate how all the noise we make adds another, barely recognised, dimension to the loss of biodiversity that all of us bemoan. While we recognise many overt ways in which cities displace wildlife by destroying/ transforming habitats, we are only just beginning to understand less visible impacts, like the steady, growing hum of traffic and industry, which alter the behavior of animals in cities.

Like us, many animals use sound to communicate with their mates, competitors, even enemies-and birdsongs offer the best examples. Birds use a variety of sounds, from simple chirps/ whistles to elaborate songs rivaling the finest tunes on your FM radio. More complex songs are used by males to attract mates and warn territorial rivals. Typically, males with bigger repertoires and more complex songs are more successful in courting females and fathering young than those who hum but a few bars of one tune. What’s more, avian pop charts also vary from station to local station, resulting in regional dialects. Some birdwatchers can identify different bird species by their voices, even among the duller look-alike warblers (the little brown/green jobs) – while keener ears can tell apart the greenish warblers that spend winters in Andhra Pradesh from their cousins who prefer to settle in Kerala.

How well sound waves carry your message depends, of course, on the medium they travel through-and background noise seriously interferes with communication. As you must know if you’ve tried making phonecalls while stuck in traffic, or sustaining a philosophical discussion during a dinner party, the noisier the background, the harder it is to convey your message or understand what others are saying. Birds have similar problems: males are unable to show off the full extent of their vocal repertoire, especially subtle vocal modulations, if their habitat is too noisy; and females suffer because they cannot find the best males, thereby losing the chance to produce sons with mellifluous voices and daughters with a keen ear for a good song who will in turn produce the most grandchildren (for that, indeed, is what the evolutionary game is all about). A recent study found that Australian zebra finch females, given the choice between different male songs (in the laboratory where they heard recordings) were quite discriminating when it was quiet, but became rather poor in distinguishing between songs when traffic noise was broadcast alongside. Isn’t the audience always quieter-and more touchy about noise-at classical than at pop concerts?

One way birds cope with all the noise we make is by singing louder when it’s noisy-this so-called cocktail party effect is documented in some species. Urban noise also tends to be low-pitched, so an alternative is for birds to get shriller, sing at a higher pitch exactly what great tits have been found doing in Europe. A more subtle effect is for birds to simplify songs, cutting out some of the fantastic frequency modulations, harmonics, and other vocal gymnastics they are capable of-not unlike how classical music maestros may be forced to stoop to Bollywood tunes or advertising jingles to make a living! If those tricks don’t work, one must find relatively quieter times during the busy urban day to sing one’s melodies – which may be why that annoying magpie robin wakes you up at 4 in the morning.

Of course, not many species are flexible enough to make these adjustments and continue living in cities. Those that cannot cope likely go extinct locally, leaving behind a poorer urban bird community. Chalk up another reason why cities worldwide seem to be occupied mostly by the depressingly familiar contingent of pigeons, starlings and crows-usual suspects in the homogenisation of urban wildlife that’s part and parcel of the globalisation package (or so we are told-but I’ll save the discussion of this homogenisation question for another column). In the long run, if our cities keep growing, and remain noisy, we will chase away most of our more discriminating singing friends, while those that remain will sing impoverished urban dialects. And we all lose the symphony of biodiversity to a homogeneous urban cacaphony. We must all share Talom Yaying’s sense of loss-although some of us just don’t know it yet.