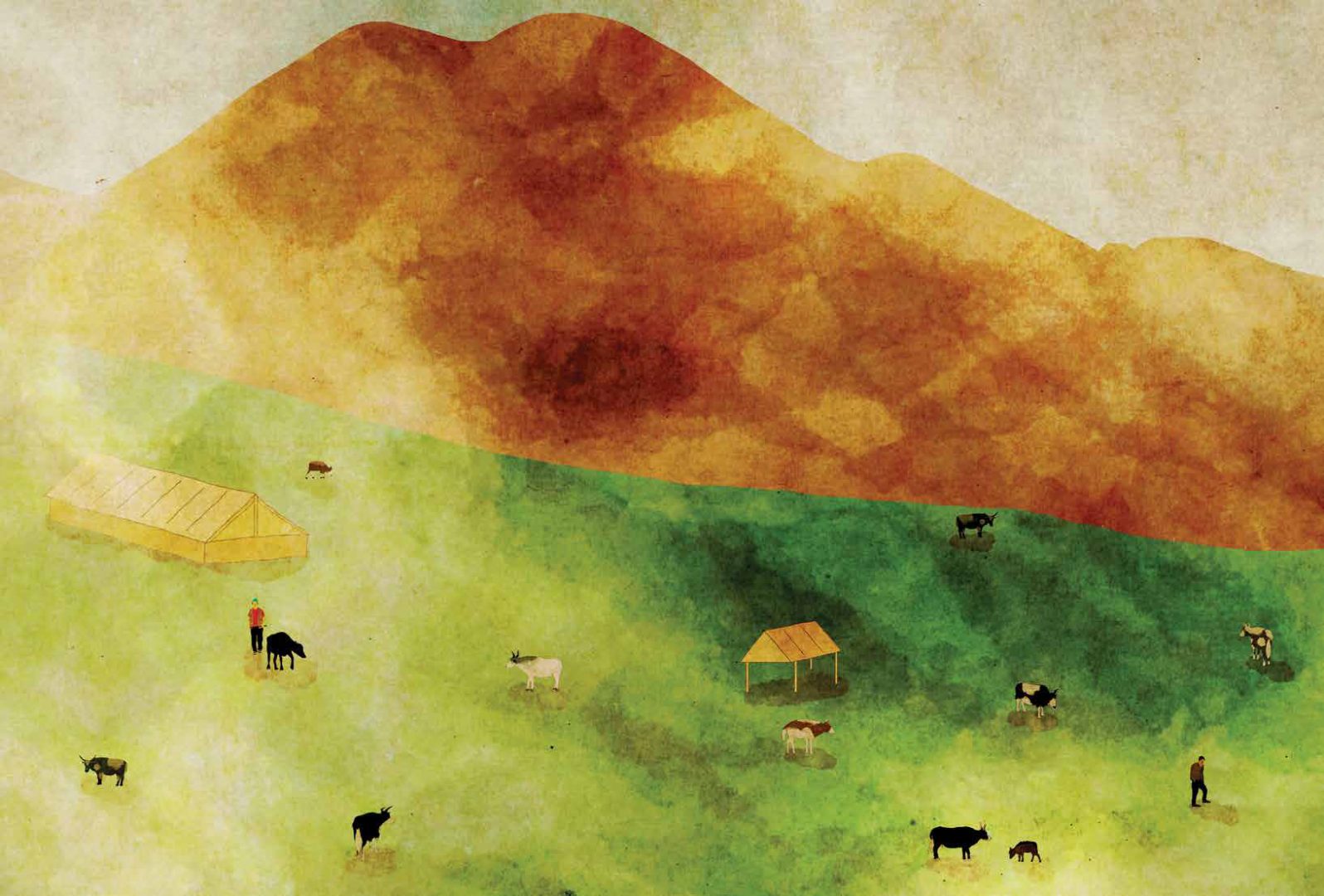

Climbing up out of the Kathmandu valley in Nepal through the Sunderjal waterworks and along the rising crest of the Thare massif toward Tibet, you pass through two small villages before finally reaching TharePathi, an isolated pasture about 50 miles from Kathmandu. In the summer monsoon months, you may hear the deep mellow sounds of lowing cattle and sonorous bronze bells well before you see the stone shelter amidst the heavy clouds and fog that envelop the mountainside at 3800m.

The cattle appear through the mist as they graze on the hillside, stumbling over rocks, standing braced on the steep slope, waiting for evening milking. They are dzomo, a cross between a yak father and a cow mother. They are all female – male crosses are called dzopkio and people in this region don’t keep them.

Livestock is kept by people in the Himalayas to provide transportation, agricultural labor, food (milk, meat, and blood), raw materials (wool, hair, and horn), and manure. Through the labor and products of animals, humans gain access to energy sources in the environment that are indigestible to people, such as plant cellulose, as well as materials needed for daily living. It is possible to combine herding, or pastoralism with agriculture, but not easy. Pastoralism requires mobility and access to adequate resources to support numbers of large animals; it can require just a few shepherds or be more labor-intensive if dairying is involved. Agriculture doesn’t move and requires intensive human labor in one spot. In the Himalayas, what you grow and what you herd is dependent on the local ecology in which you live and the historical and social factors that have shaped your culture.

The families who use the Thare Pathi pasture come from Melemchi, a village down below at 2600 m. Dzomo herding is a way of life with a long history in this valley. The region is called Hyolmo and its original settlers were lamas from Kyirong, Tibet, who established a series of Buddhist temples here in the mid-1800s. Each temple was surrounded by land and forest and ultimately grew into a village. Hyolmo villages are all situated high on the slopes of the Melemchi and Indrawati river valleys -at around 2550m. The only crops that can grow there are potatoes, high altitude wheat and barley, and at the lower spots, corn. It is the upper limit for lowland cattle (zebu) and water buffalo, which can be kept tethered and stall-fed in the village to provide household milk and manure.

Hyolmo temple villages vary in exposure, size, slope, and microclimate. Some have very steep slopes and no room for agricultural fields. Some are at the southern end of the valley and closer to roads and lower villages where rice and millet are grown. Melemchi village is spread out over a gentle slope on the western side of the Melemchi River. It is the most northern of the temple villages and has sole access to the forest resources on the hillside. Wheat, barley, and potato fields surround the houses and there is lots of open space. But it is dzomo herding that defines the village, not agriculture. As far back as living residents can remember, Melemchi families herded dzomo and they kept that way of life longer than all but one of the other 18 villages. There are no dzomo herds there today, but in 1971 when I began my work there, most residents lived with their herds. Over the years, I have come to know dzomo herding as a unique Himalayan adaptation with great time depth and much to teach us about how mountain people make a good life.

There is something incongruous about the appearance of a dzomo. Like their cow mothers, they have short hair, long faces, and long legs, and can produce a calf every year (yak produce calves every two years). Like their yak fathers, they have bushy tails, a stocky bulky body, and a physiological tolerance for high altitude and cold. In some ways, dzomo are an improvement on their parents. Dzomo produce more milk and lactate for longer periods than either cow or yak. And they have their first calf at an earlier age than either parent species. Dzomo are specialized for milk-production in high altitudes – or actually, the middle altitude zone of 2100m to 3600 m, which is too high for cows and too low for yak.

Dzomo herds are owned and managed by households; the family moves over the year with their herd, up to high pastures in the summer and low pastures in the winter. They live in temporary structures built with the bamboo mats they carry with them, although many pastures have a stone-walled floorless hut with a plank roof that provides more protection and comfort. Traditionally, men receive part of their parents’ herd when they marry, along with rights to the family pastures. The work of dzomo herding is relentless and difficult. Although a husband or wife can do it alone for a day or two, two adults are necessary to keep it going. Women do the milking twice a day, make butter, and manage the household. Men cut firewood and fodder, supervise livestock breeding, buy and sell livestock, carry the heavy equipment (churn, bamboo mats) to new pastures, and travel to resupply from the village or sell cheese and butter. Butter and cheese are made every other day. Children as young as 5 years old help with tasks at the pasture, so there is no benefit in curtailing family size. Five to ten times a year the family must move to a new pasture; some are over a half-day away. The bamboo mats are four adult loads; the household effects, another five. The family carries everything on their backs; dzomo don’t carry loads.

A dzomo herd is a dairy herd, usually 10 or more dzomo and a bull. Melemchi people prefer the dwarf Tibetan bulls because they do better at the higher altitudes where dzomo live, and they produce smaller calves called pamu, which are easier for their dzomo mothers to birth. The animals cluster around the shelter at night and, after milking in the morning, are sent out with one of the children to graze in the pasture and surrounding forest until late afternoon when they return for another milking. Dzomo are bred in the summer months at high pasture and give birth during the spring. They lactate for 3 to 7 months, including the first few months of their next gestation.

Dairy herders, the world around, face the same problem. In order to lactate, cows must give birth to calves, but dairy farmers want the milk, not the calf. The most common solution is to sell them. Melemchi herders can’t do this. A pamu is a second-generation hybrid. They have none of the vigor of their first-generation hybrid mothers. They are small, sickly, and produce less milk than their mothers. They have no market value. Kept through adulthood, they are a drain on the environment and the family’s energy and income. As Tibetan Buddhists, Hyolmo herders don’t kill animals. So, in fact, most pamu die of illness and neglect within the first few weeks of life. Some pamu are spared because their mothers won’t lactate without them and others thrive despite neglect, so most herds eventually accumulate several adult pamu.

There are other economic challenges to dzomo herding. You can’t recruit your herd from within. You need to buy your animals from people who breed cows and yaks, so you need a source of cash. Livestock is expensive so herders may buy a cheaper immature animal and raise her to breeding age, taking a chance that she may not thrive or be a good breeder. Since you can’t kill dzomo, injured, unproductive, or elderly animals must remain in the herd so ultimately the herd becomes less and less productive. Keeping a bull alive and healthy at altitudes beneficial for the health of dzomo takes knowledge and extra work. In fact, experience with and knowledge of livestock management is essential, and forms a core of traditional practice that is held in this community without access to veterinary medical care. Harsh and unpredictable weather, predators, and disease also increase economic risk and uncertainty.

In the early 1900s, residents of Melemchi had large dzomo herds and few grew anything in the village. They traded butter and cheese for agricultural products or sold them for cash to buy salt or tea or the few manufactured commodities they needed. Even though they lived with their herds away from the village, the village with its temple or gomba was the center of community life. The land surrounding the gomba is endowed for its support, so even those out with herds are members and are responsible for maintaining the gomba and for its annual ritual cycle. Physical labor, as well as taxes in the form of grain, butter, or cash, are required from each household. Eventually, some people built houses in the village, for their old age, or to store things, or to live in when they were between herds. As families and herds grew in size, they could spare time and people to manage both crops and herds, so house numbers grew. Agriculture began to be more practical when people were around to do the work. Economic diversification reduces risk in an uncertain and harsh environment.

The dzomo herding system, combined with winter rain-fed annual crops like wheat, barley, and potatoes, provides a flexible subsistence system for families in Melemchi where there is access to excellent pasture above the village, a large open village space with good water sources, and a low population density.

Over the twentieth century, Melemchi grew into a large village, with increasing numbers of houses. When my husband and I lived there in 1971, wheat, barley, and potato fields occupied the central area and 24 families herded dzomo. There were 30 houses in the village, but only 6 were lived in year-round. The others belonged to herding families whose members occupied them for short periods to tend crops or help with village work. By 1986, the fields remained but there were 78 houses and the number of herds had dropped to 20. Still, lots of those houses were empty – in addition to absent herding families, other families were building roads and working construction in Tibetan Buddhist areas of the Indian Himalaya. People moved back and forth throughout the year, bringing back money for houses and living expenses for themselves and their relatives, and in a few cases, for new herds of dzomo. Today there are more than 125 houses, as well as a school, seasonal road access, and electricity. The agricultural fields are still there, with new housing and the school built on the edges. Many Melemchi people live outside the village and send money home to their families remaining there.

Diversification and flexibility are hallmarks of successful mountain communities everywhere. In the Nepal Himalaya, at 2600 m, the dzomo, a hybrid yak-cow, built and sustained a Tibetan Buddhist lifestyle for thousands of people into the twenty-first century. While no one in Melemchi today herds dzomo, there are still dzomo herds in a few Hyolmo villages, as well as elsewhere in Nepal. Young and old continue to live in Melemchi, or maintain their houses there for future visits or residence following their stint as global workers. The children and grandchildren of our herder friends may live in Kathmandu or abroad, yet they return often to visit and participate in village business and ritual obligations from afar via satellite phones and social media. Regardless of residence and current occupation, dzomo herding continues to define a heritage that is now spread around the globe. Many Melemchi people living today in places as far-flung as Korea, Crete, Qaatar, and Jackson Heights, New York grew up in dzomo herding families and carry that knowledge, heritage, and conviction into their lives and into their futures. It defines who they are and provides sustenance and value as they encounter new challenges.

Further Reading

Bishop, Naomi. 1998. Himalayan Herders. Harcourt Brace and Company. (reprinted 2002, Thomson Publishing).

Photographs: John Bishop