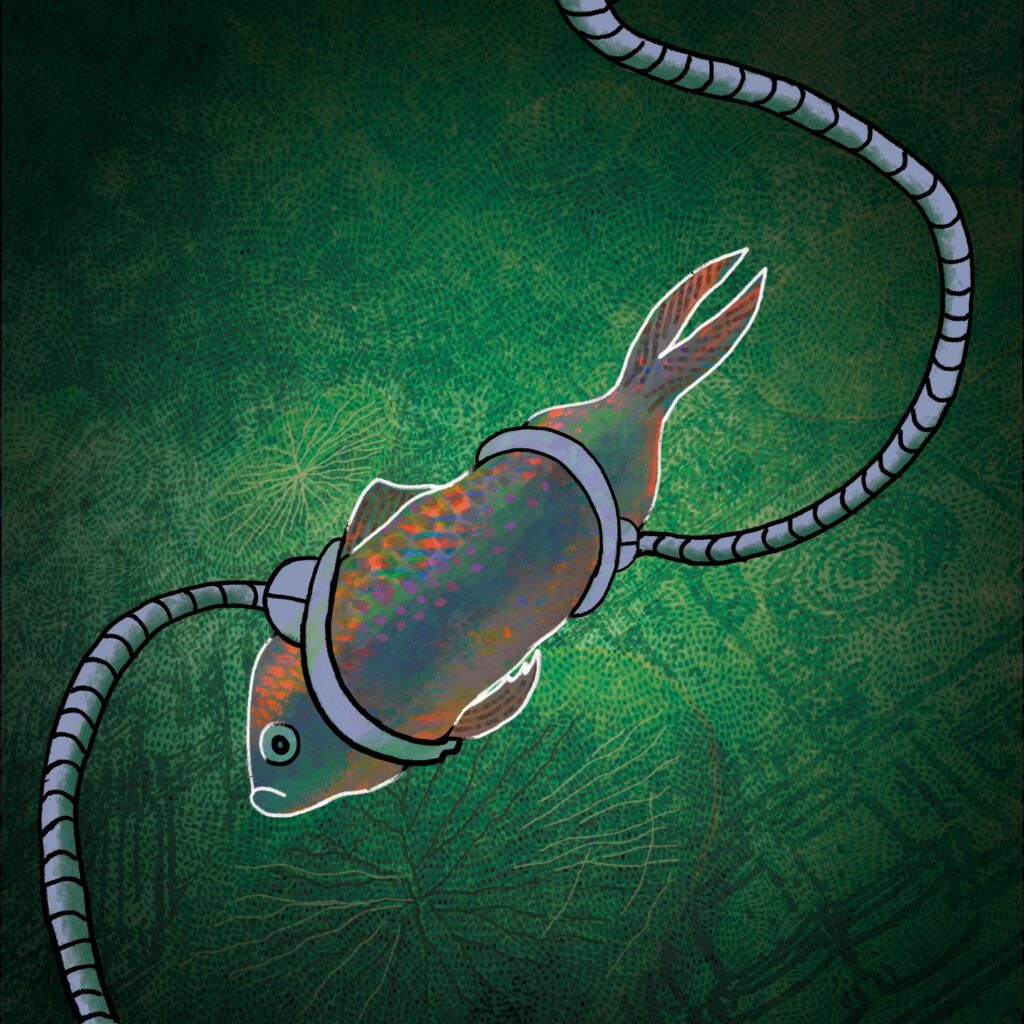

I spent over two months working in Panna Tiger Reserve, and yet, the first and only time I saw a tiger there was on my first day. The setting sun cast a golden hue on the grass fields of Pipartola, and set the Ken river on fire, as a radio-collared tigress leisurely strolled across the rocky riverbed. The distance was great enough that I needed binoculars to get a good look at her, but the moment was perfect. And yet, while that was the only time I ever saw a tiger in the Reserve known for its successful reintroduction of the species, Panna never let me feel like I was missing out.

From leopards to mahua trees, chousingha (four-horned antelope) to vultures, my time in Panna was full of new sights, sounds, and even smells, that kept me constantly at the edge of my seat, wondering what there was to see around every turn of the winding, rocky roads, what new sight to take in or new behaviour to observe.

Many tourists feel a safari is incomplete until they have caught a glimpse of the big cat. I don’t blame them—my own family was disappointed to have missed out on a tiger sighting, despite multiple early morning safaris in the biting cold of December. Tigers are magnificent creatures, and few animals measure up to the glory of a wild tiger in its prime. Yet, in this fervor to get a Sighting (with a capital S) people often miss out on everything else the forest has to offer.

At Dhundhua, a small stream runs from a shallow, rocky bed to fall a few hundred feet in a rainbow-making spray that lends the place its name. Vultures—mostly long-billed—will gather gregariously right at the very edge of the cliff where the water falls, occasionally bathing, squabbling, or sunbathing. When you cross this stream and arrive at the viewing point, you see a gorge, nestled in which is a dense jungle. Tales are told of roaring tigers wandering the bottom of the gorge, cubs in tow, providing excellent photo opportunities to lucky tourists.

Arriving at Dhundhua involves a rapid-fire of wildlife sightings, one after the other in dizzying succession—an Oriental hobby sits on a tree by the cliff, orange chest puffed out in the cold. A red- headed vulture looms on a skeleton-like snag in the distance. A painted francolin bursts out of the brush and careens across the road like a headless chicken. A chinkara (Indian gazelle) skips before a line of parked Gypsys.

To one side the stream falls, and stretching from the stream to beyond in a vast circle are the cliffs, on which the long-billed vultures roost. Ficus trees sprout, defying gravity, emerald against the sheer cliff walls. The canyon seems empty until you take a closer look, and see the scores of vultures lining the crevasses, huddled together or singly, all along the canyon. It’s a breathtaking sight, and gives one hope for the future of plummeting vulture populations.

We drive down the red dust roads beyond Dhundhua, over narrow paths winding through the patchy dry deciduous trees, mostly leafless in the December cold, the trees dwindling until grasslands stretch into the distance, dense scrub just beyond. The path widens and we reach a charming but empty forest rest house, meant for visiting dignitaries, but which offers an ideal lunch spot for others. There, we can disembark to eat our packed breakfast of fruits, and my parents and brother receive the gift the wild so often gives me—silence. The wind blows through the grasses, the birds chirp intermittently, and not a single Gypsy vehicle can be heard, no tourists venturing so far into this zone, where tiger sightings are few. In that clear, cold air, I imagine that my family too feels some of the city dust being gently blown off their souls, and some of that peace I feel whenever I am lucky enough to tread these wild places.

As the sun climbs higher, we make our way back down the valley to Pipartola-by-the-Ken. The scattered ber trees have a browsing line so sharp, from the nilgai and chital (spotted deer) feeding on their boughs, that it looks like a very conscientious gardener was let loose in the park. The sandy road bears tiger pugmarks and tyre prints, but the branches of a nearby tree are so full of yellow- footed green pigeons that you can’t tell the tree is bare and leafless, and so we forgive the tiger for avoiding us.

A chital, its antlers still wrapped in soft velvet, chews on the old, shed-off antlers from a season past, replenishing its lost calcium. Another, feeding on leaves, stares at us blankly, dried velvet peeling off its antlers in bloody tatters, and I am reminded that nature isn’t averse to blood and bone like humans are.

If you take a boat ride down the Ken river, the fun continues. The water is jewel-green, and one of the many explanations people give for the National Park’s name (Panna means ‘emerald’) is for the colour of the river. A mugger crocodile basks on a rock, almost blending in. A pair of lesser adjutant storks settle on a tree, too far for my camera to capture in the shaking boat, but with binoculars we can make out their balding, combed-over heads.

When I leave Panna, my heart is lightened. My stay has rejuvenated me, but it is time to say farewell. The tigers may not have, but Panna blessed me with an abundance of life, sharing—as she does—her riches freely. I hope you, too, visit and are blessed with these riches. I hope you don’t miss the forest and its many denizens for the tiger.

Further Reading

Bold and Beautiful: Panna’s Glorious Tigers. RoundGlass Sustain. https://sustain.round.glass/species/pannas-glorious-tigers/. Accessed on 20 February 2021.

Chundawat, Raghu. 2018. The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers. New Delhi: Speaking Tiger.