Feature image: A reef egret seen off the coast of Gujarat

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as life for most people shifted indoors, reportage revolved around how the rivers had cleaned themselves and wildlife were reclaiming the empty roads and highways. This supported the belief that all nature needs to heal and flourish is a bit of space, time and support.

This became personally evident when, in the last week of 2021, I got the opportunity to travel to two marine projects that the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) is running in Gujarat—the Coral Reef Recovery Project in Mithapur and the Whale Shark Conservation Project in Veraval.

These visits were also special because in the last decade that I had spent working for wildlife conservation, I was fortunate to traverse a wide range of landscapes—from evergreen forests to barren deserts. For a brief duration, I even got to work and travel in alpine regions. But the sea had eluded me all this while.

Underwater forests

The Coral Reef Recovery Project began in 2008 with the creation of an artificial reef system. It is also the only one of its kind that is managed through a public-private partnership between the Gujarat Forest Department and Tata Chemicals Limited (TCL). Coral fragments from Lakshadweep were introduced in artificial nurseries in Mithapur to support the degrading habitat. Today, these artificial reefs have helped bring back some unique marine life, including bottlenose dolphins, four species of seahorses and several nudibranchs.

The colours had already started changing as the train passed Jamnagar, heading towards the coast. Praveen, WTI project head at Mithapur, came to receive me at Mithapur station. The Mithapur township is majorly dependent on two things—TCL’s Tata Salt, an integral part of most Indian households, and fishing, which comprises the livelihoods of most of the locals.

Acting as nurseries for baby fishes, the local fishers understand how important coral reefs are for their livelihood. Additionally, designated no-fishing zones around the artificial reefs ensure that populations are able to recover. Thanks to this, the fish stock has increased since the project started.

My first ever scuba dive was scheduled for the next morning. I was nervous, but I had always wondered what it would be like to dive into underwater forests and swim with colourful shoals of fish. Along with Charan Kumar Paidi—field biologist and certified Dive Master—I loaded our oxygen tanks onto the boat and off we went.

As luck would have it, the water was crystal clear that day. With Charan’s guidance, I navigated around the artificial reefs, mesmerised by things that I had seen only in reports until then. While he recorded the health data of the corals, I was chasing after groupers and sturgeons! We were merely 10 feet below the surface, yet in a wholly different world.

Home to the Vhali

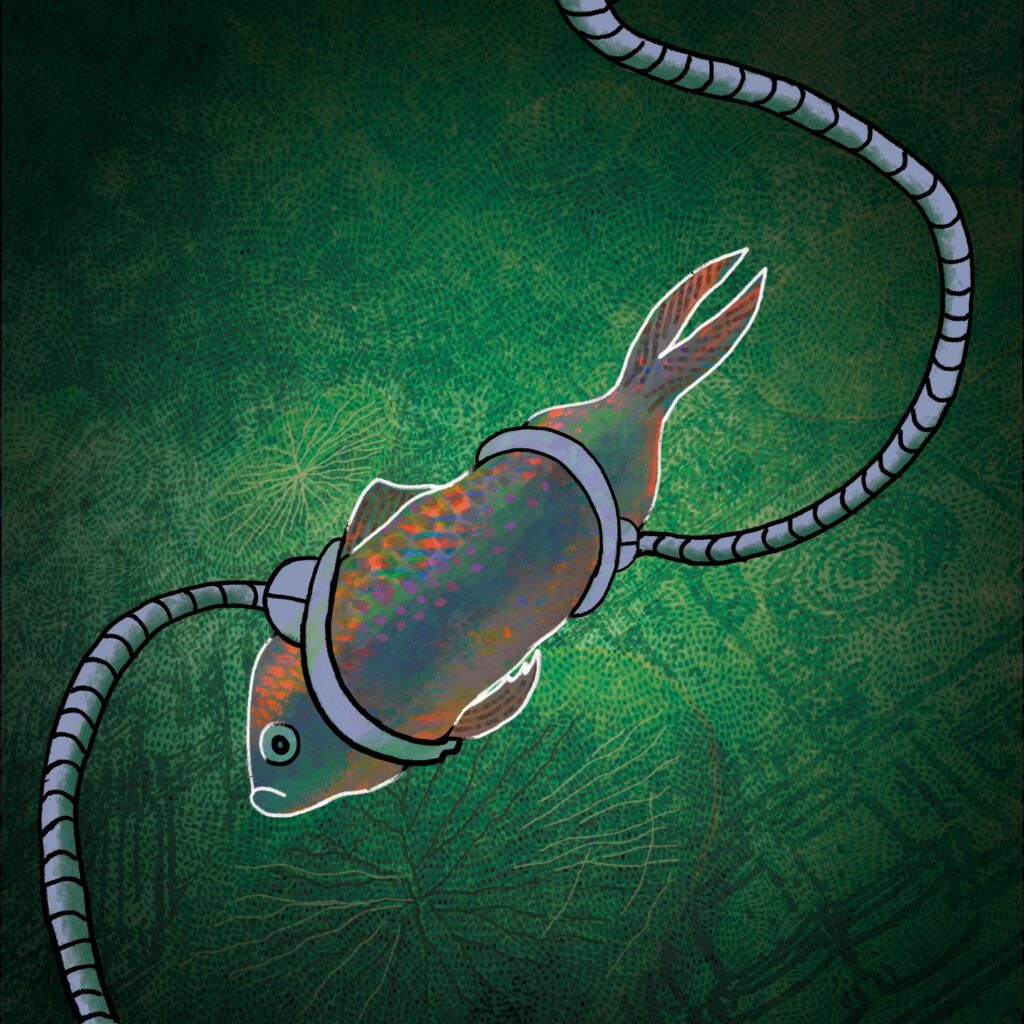

About 250 kilometres from Mithapur, I arrived in Veraval—a port city famous for its fishing industry—before the sun came up. This is also part of the Indian coast with the most frequent sightings of whale sharks. Two decades ago, the whale shark—the world’s largest fish—was heavily hunted for its fins and liver oil. The year 1999 alone reported more than 600 landings of whale sharks and that was when conservationists began focussing on its protection.

WTI ran massive conservation campaigns from 2004. People eventually came to understand that this was a chosen site where whale sharks came to raise their pups, just as in traditional Indian families where daughters return to their parents’ homes with newborn babies. Thus, the whale shark, a fish that was hunted, became Vhali or “the dear one”. A scheme was put in place by the Gujarat Forest Department that reimbursed fishermen for the loss of their nets when they released whale sharks entangled in drag nets. Together with Tata Chemicals Limited, WTI was able to transform the whale shark into a symbol of pride for the port city.

There isn’t a single fisherman who doesn’t know Farukhkha, the manager of the Gujarat Whale Shark Recovery Project and a sociologist by training. On my first day in Veraval, we were at the dockyards by sunrise, where I witnessed firsthand how the port operated. I realised that the place never slept. Fishermen spent entire nights out at sea and when they returned, the harvest went through the process of unloading, auctioning, processing and more. Kids played in the surf, while women were busy stitching nets together. These were people who depended on the fish they caught for their livelihood. Yet, they didn’t think twice before slashing their nets to release entangled Vhali back into the waters.

Around 11 AM, Farukhkha received a call. A whale shark had been accidentally caught three nautical miles offshore. When we finally arrived at the spot by boat half an hour later, the fishermen were already cutting off the nets and for the next five minutes, all eyes were on the massive blue polka-dotted fish. To a background score of claps and cheers, the fish soon glided its way back to the depths of the ocean. I was ecstatic—not many people get to see a whale shark and I had seen one on my first day!

Over the next couple of days that I spent in Veraval, I learnt more about the relationship of the locals with their Vhali. The conservation campaigns had resulted in massive participation across demographics, from corporates to local businesses and school kids to the elderly, all part of the “Friends of Vhali” group on a mission to protect their daughter.

Change is possible if we can fight for it together and when we stop thinking of nature in terms of resources. Wildlife conservation is more than spending a night in the jungle or seeing a tiger in a safari. It’s about people, beliefs and empathy.