Platanista’s predicaments

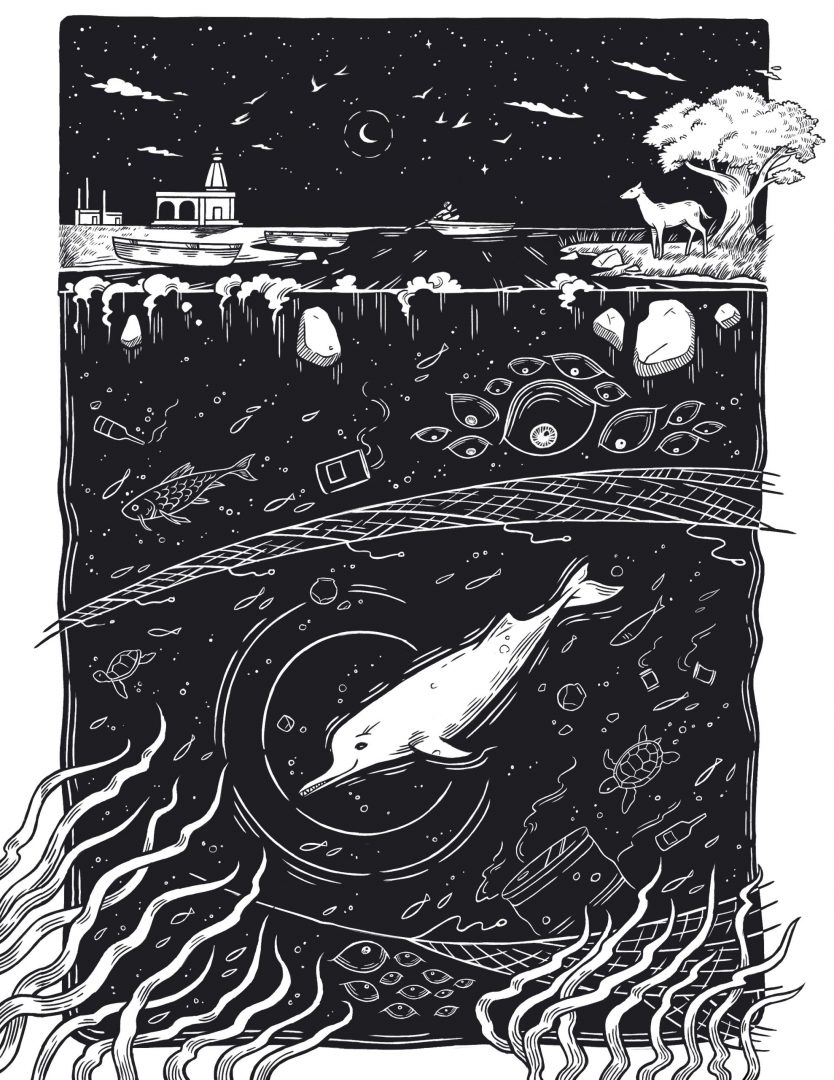

Perceptions of the Ganga in India are often as diverse as the many states the river flows through. From being a living embodiment of a Hindu Goddess in one, to just a navigable channel in another, the Ganga oscillates in identity. One section of society ascribes ‘personhood’ to the Ganga while another abuses the river for economic benefits. Even people who believe in the holiness of the Ganga, litter and pollute. Devotion, it would seem, is not equal to reverence. The river is, therefore, constantly shrouded by a fog of duality and contradictions. So is the case for an inhabitant of the Ganga, the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica).

The Ganges river dolphin is the national aquatic animal of India, yet this animal is threatened by a wide range of issues, including declining water levels, increasing pollution, depleting fish abundance, and greater traffic in the rivers. But among these factors, one issue, a kind of pollution, is often overlooked. The pollution that I speak of is not the well-known chemical or industrial pollution of the water but a far more subtle pollution that severely affects the Ganges river dolphin: noise.

To understand why noise pollution is problematic for the river dolphin, we need to understand the animal’s biology. Unlike its marine cousins, these ancient cetaceans have almost lost their visual powers, probably because eyesight in a sediment-rich river is not a very useful sense. These dolphins navigate and forage by producing high-frequency clicks, much like bats do, to echolocate in the dark and murky waters. The dolphin relies on sound not only for navigation, but also to communicate with one another and to hunt.

People who haven’t seen the Gangetic dolphin often assume that, like their marine counterparts, they too are athletic when they dive. However, this dolphin only does the bare essential required to breathe; it will only breach the surface, ever so slightly, exposing its blowhole right behind the head, and silently plunge into the murky water to resume swimming in an unconventional manner.

Unconventional because this dolphin is a side swimmer and at times, uses its flippers to sense the bottom of the river, probably to orient itself. Most of the time, one can only see their arched back, head and the snout studded with sharp, pointed teeth. But on certain occasions, the animal will leap out of the water gloriously and dive in head first, showing that it too is capable of acrobatic skills. Although the river dolphin does display such diving behaviour during courtship periods, this behaviour is also characteristic of stress and is probably a response to motorised vehicles plying close to them.

In the 21st century, given the volume of traffic and noise in the river, stress is probably a constant for the dolphins. One needs to only look at China to witness the threats that increasing river traffic may lead to. Following the development of the waterway in the Yangtze River, continuous vessel movement and dredging became the ‘final nail in the coffin’ for the Chinese river dolphin and it was labelled extinct in 2008.

Because of our reliance on sight, it may be difficult to imagine the sonic perceptions of a river dolphin. However, an analogy with light may make this clear. Imagine being exposed to harsh and blinding stroboscopic light for every single hour of the day. It is sure to leave you blinded, disoriented and exhausted. What the Ganges river dolphins perceive when exposed to noise may very well be the same.

However, there is more to the Ganga than noisy vessels and dirty waters. Beyond the polluted waters and vast agricultural fields, there exists a land where otters and jackals roam without boundaries, where riverine birds flock by the hundreds and fishes as large as humans still dwell beneath the river. In the popular discourse, we hear how polluted and filthy the river is – which is true – but we miss out on other stories of the river. In trying to understand how noise affects the acoustic behaviour of dolphins, I have begun to appreciate this other side of the Ganga that is rarely seen but is frequently heard. Out in the floodplains, the unseen captures your attention. Despite all the problems associated with the Ganga, and the popular notion of it being a ‘dead’ river, the part that flows through in Bihar still resonates with sounds that befit the living. This ‘other’ Ganga that I wish to write about is surrounded by charismatic animals on land, in water and air; areas that still retain their rustic nature, might and ‘wildness’ as was documented in the 1920s by the Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay in his book, ‘Aranyak’. A place that triggers a sense of being lost in time.

Riverine symphonies

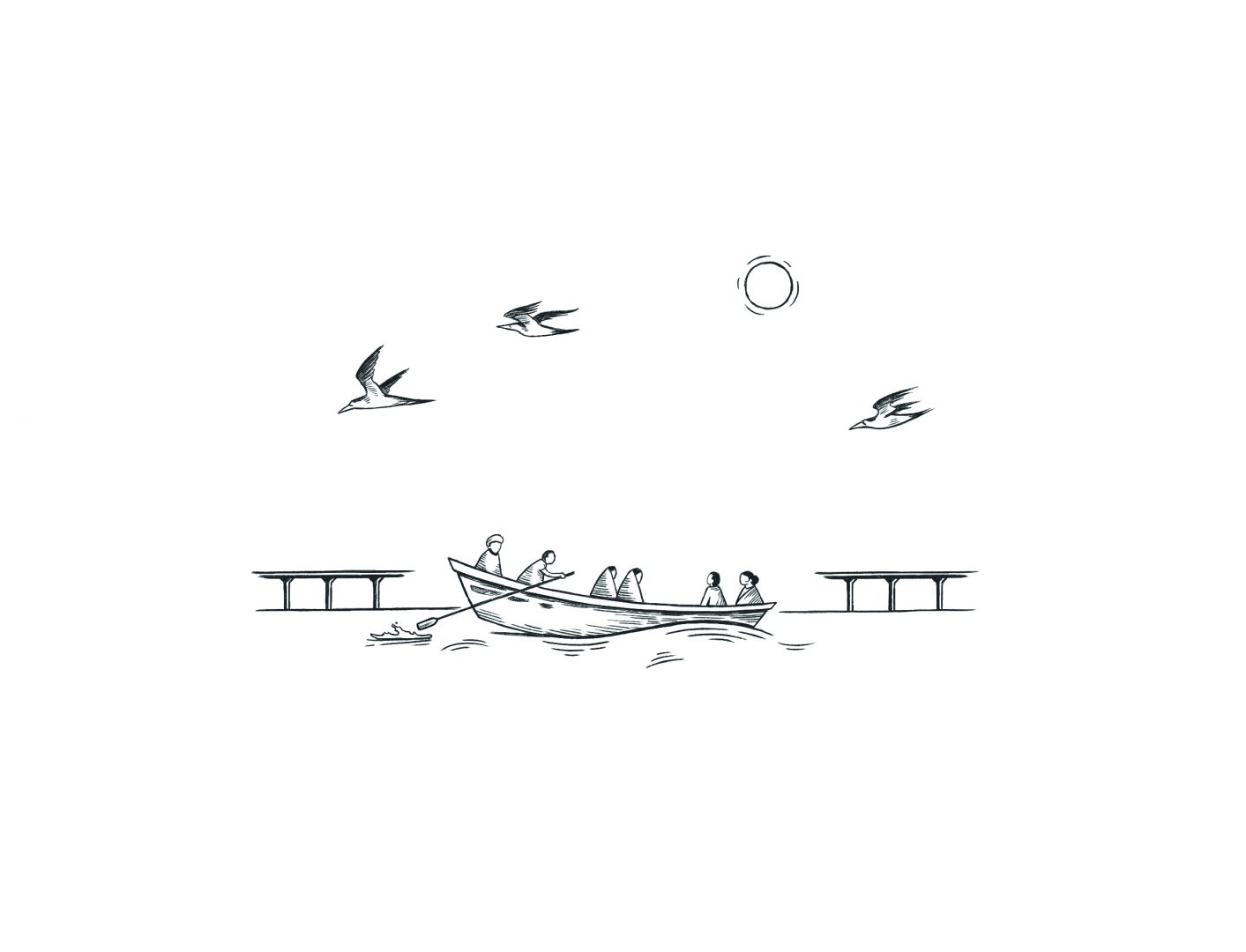

The Ganga, especially in the northern state of Bihar, is a breathtaking place. The river and its floodplain is a vast expanse of sand and silt, bordered in most places with a carpet of agricultural lands as far as the eye can see. The river itself, in some places, is about three kilometers wide and looks like the sea. After sundown, however, one starts to sense the landscape not through sight but through sound, similar to a river dolphin. A particular incident during my fieldwork made me experience the night-time ambience of the river and remains etched on my mind.

I was based in a small town called Kahalgaon in Bihar right on the banks of the Ganga. At about 3:00 in the morning, as my boatman and I climbed down to the water’s edge to place our sound recorders and underwater microphones in the water, the howling North-Eastern winds that blow during March and April created ferociously crashing waves on the river. Our small fishing boat stood no chance in navigating the river in this tempestuous weather. However, the storm didn’t last too long and disappeared as swiftly as it had arrived. The ambient sound too changed dramatically. Soon after the roaring winds and crashing rain, all we could hear was the gentle lapping of waves against the hull of our fishing boat and the sound of the oar breaking the water’s surface. As we sailed across the river, a lone Ganges river dolphin started trailing our boat. These animals are known to follow small fishing boats at night in hopes of getting an easy meal from the scattering fish when the fishermen start hauling their nets. Although you cannot see much in the dark, the river dolphins reminded us of their presence by breathing air out of their bodies with a characteristic ‘sus’ sound. This sound is why these dolphins are known as ‘sus’, ‘susu’, ‘sons’, and ‘hu’, in various vernacular languages.

Experiences such as the one I describe are rare, but there is beauty even in the ordinary, if one looks, or rather listens, in the right direction. A traveller visiting for the first time may even turn back because of the cacophony that one perceives as he or she travels through the cities of Bhagalpur and Kahalgaon. But, in a sense, exposure to this din in the city is crucial in appreciating the more comforting and peaceful sounds of the river and its floodplain. This peaceful riverine orchestra is in fact quite rewarding if you listen close enough, for the musicians in this symphony are both human and non-human in nature. The wind and the rustling sand, during morning hours, form the foundation of the song, with the occasional motorboat acting as the bass, while the shrill calls of little terns, common ringed plovers, sandpipers, river lapwings, Eurasian curlew and small pratincoles form the melodious high notes. The soloist in this orchestra of the floodplain is the farmer who sings with his alto voice, a haunting tune that echoes through the vast floodplains.

However, come nightfall, the soundscape along the river changes drastically. Once, my boatman and I were camping on a river island near the town of Kahalgaon. His boat was anchored off the island and was gently swaying along with the waves. After dinner, I decided to take a stroll along the island and absorb the gentle sound of the flowing water. The peace and tranquillity that I felt was absolutely mesmerising but little did I know that the midnight symphony of the Ganges was about to begin.

Past midnight, the crescendo of the wind becomes noticeable, and like the wind in the dawn orchestra, formed the bass and keynote for this midnight symphony. The waves too, emboldened by the wind, created a soothing, crashing sound, with water bubbling in the sand. Nearby, filling in the role of cellos, ruddy shelducks took flight and called. Their calls, although quite eerie in nature, fit the vast, moonlit darkness of the river. Whatever caused the disturbance to the shelducks soon moved nearer and displaced a dozen greater adjutant storks. Their wings produced the percussions that were necessary to complete the low notes of this soundtrack.

Like curtains rising to show the playwright of a play, a shrill laughter erupted from the grasslands, revealing the disturbance that led to the dramatic flight of the birds. The characteristic call of jackals was unmistakable. The jackals caused a ruckus among the nesting lapwings and their calls along with the alarm cries of the lapwings added to the much needed soprano of the composition. The end of this midnight symphony was heralded by a hunting river dolphin which, while chasing fish in knee-deep water, kept slapping its jaws, producing a very apt applause for the performance.

Navigating nature

Noise and tranquillity; wilderness and civilisation; filth and reverence; dolphin and destruction, existing cheek by jowl in the Ganga, challenge our notion of where wildlife should exist. Usually, when we visit a protected area, we are often surrounded by all things ‘natural’ and devoid of anthropogenic developments. However, river systems, like the Ganga, are strange places. One can experience both ‘wilderness’ and ‘civilisation’ within a span of 24 hours. The same river island, overrun by people who depend on the river for their livelihood during the day, can transform into an island that harbours exciting wildlife, rich with drama, during the night. Unfortunately, this fragile and boundary-less nature that exists in the river also experiences threats more intimately than areas that have been cordoned off for protection.

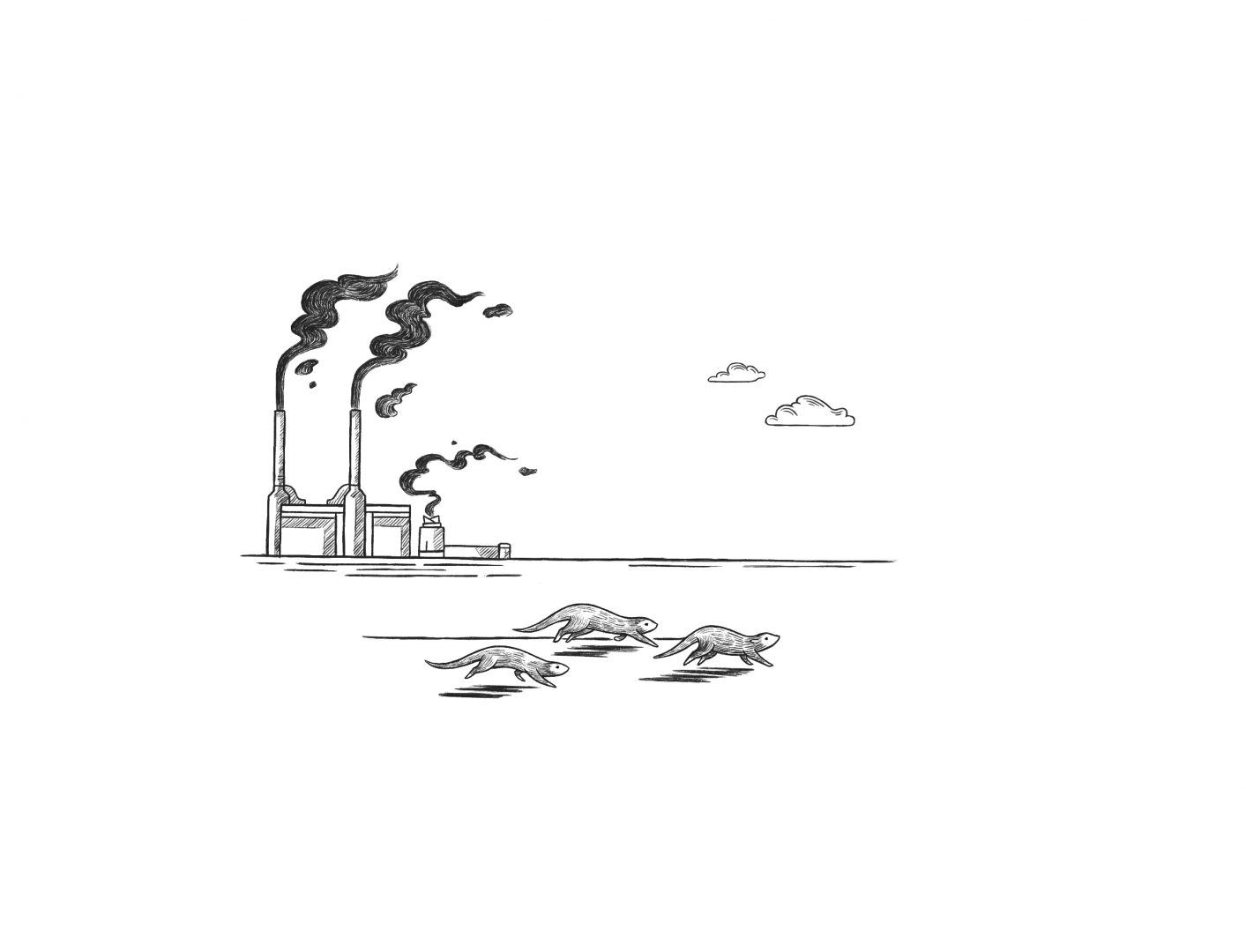

With rapid development of waterways looming in the immediate future, experiencing the river and its natural entities may soon be a thing of the past. The proponents of the national waterway which include several ministries of the government such as the shipping and water resources, road and transport and ironically, the Ganga rejuvenation and development, argue that waterways are in fact, ‘eco-friendly’, since the amount of fuel consumed for transporting materials over water is much less. Their arguments may make economic sense but make very little ecological sense since continuous dredging, alteration of river flows and construction of embankments and dams need to be ensured for navigation on the river. Hence, here too, the identity of the river is being contested with one section lobbying for economic growth while the other section argues for ecological stability.

The rapid development of the waterways not only threatens the Ganges river dolphin but can also impact other organisms that depend on the river for their survival. Although tigers, sloth bears, and wild buffaloes that once roamed the land have gone extinct, otters, fishes, nilgais, wild pigs, jackals, the occasional gharial and mugger crocodile, hyenas, diverse waterbirds, and the shushuk (dolphin), still inhabit this timeless place. However, the fact that the dolphin and other wildlife still manage to survive here should not mislead us into thinking that the busy waterway has no impact.

If one is to develop and rejuvenate the Ganga, it is crucial to view the river through an ecological lens and not solely through an economic lens. The hydrology of the river, the status and health of other biodiversity, along with the community of people that depend on the river need to be taken into consideration if one is to revive this ‘dead’ river. Bihar remains one of the only states where rivers such as the Son, Gandak and Ganga run relatively free, without any major alterations to their flow. Instead of viewing this as an underdeveloped state of rivers, it should be viewed as a source of inspiration on how rivers need to flow.

Some dualities in the river lend character, whereas others reduce it. Therefore, it becomes crucial that we as a community see not just one aspect of the river but also appreciate and honour the more nuanced bits that often go unseen and unheard. If only we were to use this sense of appreciation and reverence as regularly as our sense of gain and profit, much of the harmful dualities will cease to exist.

Link to the soundtrack:https://soundcloud.com/mayukh-dey-533977316/riverine_symphonies