Feature image: Red-vented bulbul on a guava tree (Photo credit: Usha Kiran)

In India’s increasingly dense and noisy cities, nature can feel like a distant memory—especially in everyday life. But what happens when something wild and delicate returns to our attention? This essay begins with an ordinary moment at home—birdsong heard over the din—and follows the song into questions of memory, design, healing, and agency. It weaves the personal with the architectural, and the ecological with the emotional, to explore how small, intentional gestures in our built environments might help bring back not just biodiversity, but a deeper sense of presence.

I live in the middle of the city, and as is common in most Indian cities, the day begins with a cacophony of sounds. Cars honk, motorbikes speed by, autos rattle, people chat and walk, and occasionally, a cow moos in the distance. The sounds are unique and varied, but in many cases, they blur into a constant hum—much like the urban symphony depicted in Kalki Koechlin’s spoken word poetry about Mumbai titled Noise.

This constant hum in my neighbourhood is no different. It is a blend of uninspiring noises I’ve grown accustomed to ignoring. However, in recent years, a new addition is drowning out everything else when I hear it: birdsong. I’ve lived here for 28 years, but the birdsong is a new arrival. The melodious chirping breaks the monotony of the day, lifting my spirits every time I hear it. Sometimes, I imagine what they might be saying: a cheerful “Hello!” to a friend? A remark about the weather? Or perhaps an excited exclamation—“Oh, did you notice the pomegranate tree is flowering?” Whatever their conversations, they make me feel lighter, happier.

Often, the birds perch right outside my window on the yellow trumpet flower tree, or flit across the street, landing on bright red blossoms of another tree. Their songs fill the air, shifting in intensity as they move. Sometimes, multiple species call out at once, and for a brief moment, I feel as if I’ve been transported to a peaceful nature trail.

This simple joy of birdsong not only connects me to nature but also serves as a reminder of its profound healing power, something science increasingly supports. Practices like shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) have been used since the 1980s to harness nature’s therapeutic effects. Research shows that interacting with nature can improve a person’s mood, reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, and even lower blood pressure. Simply observing nature offers significant health benefits.

Designing for nature

As cities expand and urban life becomes increasingly fast-paced, opportunities to connect with nature are dwindling. Back in 2017, while studying architecture in Ahmedabad city, Gujarat, I found myself asking: what if our built environment itself could encourage interactions with nature? I explored this idea through a research project where we were asked to design an architectural programme for leisure (excluding food and beverage), with a specific street assigned as the study site. During a site visit, I became fascinated by the bird-feeding culture I observed. And this led me to develop Urban Leisure with Birds—a proposal to integrate bird-friendly interventions into the city’s built environment.

The goal of my project was to create a secondary architectural programme that encourages interaction with birds within fully functional public amenities, such as bus stops, banks, and post offices. Because of the high footfall and nature of these spaces where people often have to wait, they often experience an idle moment of pause—an opportunity to reconnect with nature in the midst of their daily routines. Interventions in these middle spaces of urban life could have taken various forms, from setting up bird centres for citizen science to nurseries growing native plants designed to attract birds, but I proposed using the Miyawaki Method of afforestation.

This method works by fostering dense vegetation within a 3×3 metre space, creating a thriving ecosystem within three years. While this rapid greening has gained popularity in cities, it’s also important to acknowledge recent critiques from ecologists and practitioners. They argue that such dense vegetation may not reflect the original ecological structure of certain regions, and could require ongoing human intervention to sustain. Even so, the core value of the method lies in rethinking how much biodiversity we can invite into small, overlooked spaces. For me, it became not just a design solution, but a way to ask: how can we build with birds, bees, and butterflies in mind?

My final project submission was a proposal for a bird centre called Correa Bird Centre, situated at a major bus stop in the Navrangpura neighbourhood. The design responded to the constraints and possibilities of the existing bus stop, which faced the road directly. A dense thicket was developed at the far end of the site, creating a layered spatial experience that ranged from high-traffic areas near the street to more secluded, immersive zones. The spatial gradient emerged organically—the thicket, least frequented, became a quiet refuge, while the edge facing the road saw the most movement. Perches were positioned along this public-private continuum: the tallest near the road, the lowest nestled in a clearing within the thicket.

Without signage or barriers, the spatial design subtly guided visitors, like a gentle nudge, toward stillness, pause, and, perhaps, more attentive presence. In addition, the thicket was proposed with an emphasis on planting native species suited to the local ecology, a key consideration in cities full of exotic trees that can rapidly spread beyond their bounds. The proposal suggested placing bird-friendly interventions approximately 800 m apart—about a 10-minute walk from one another. This would create a network of natural spaces interwoven into the urban fabric, offering city dwellers moments of serenity while supporting local bird populations. (I was thrilled when my project was featured in an exhibition at the London Design Biennale in 2021.)

Start now

While I found working to integrate nature into urban spaces compelling, I only truly understood its impact a few years after we moved to our current home, when local authorities cut down all the trees lining our street to widen the roads. My father, a nature lover, was undeterred, and began planting saplings along the street himself. These trees have since grown tall, providing shelter to bees, cuckoos, mynas, visiting parakeets, bee-eaters, and more.

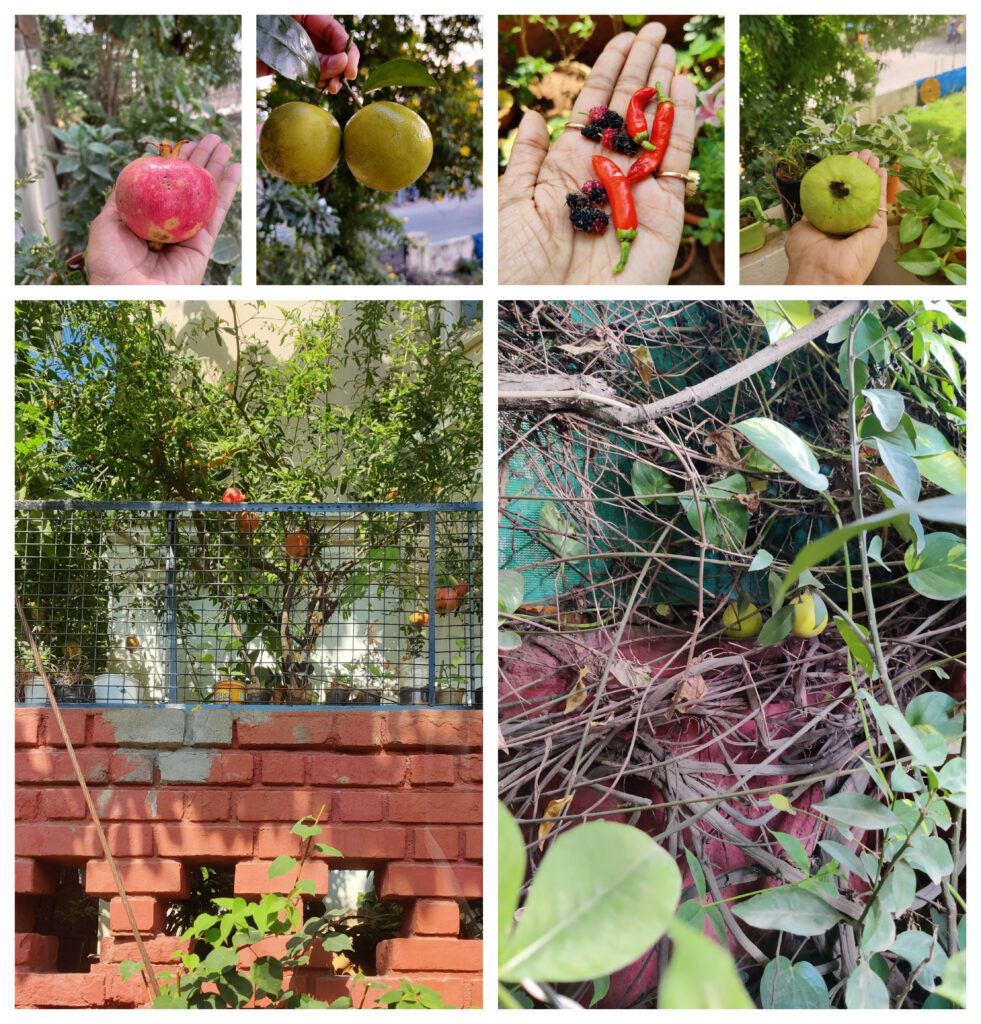

The perimeter of our own house is lined with plants. At one point, our garden looked more like a nursery or mini-forest than a human residence, with over 750 potted plants. We planted a variety of native fruit-bearing and flowering species, creating a sanctuary for birds, butterflies, squirrels, as well as toads and tadpoles. Birds built nests, huddled together on branches in the winter, and filled our days with their songs—which I deeply appreciated when we were confined to our homes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Large-scale urban interventions—such as bird-friendly spaces around public infrastructure—are wonderful, but we don’t have to wait for a mass movement to invite nature into our lives. Even small, individual efforts can make a meaningful difference. As we plant, nurture, and create spaces for nature to thrive, we invite something magical back into our lives: the simple joy of birdsong. And perhaps, in their melodies, we’ll find a moment of stillness, a breath of peace, and a reminder that nature belongs in our cities—and in our hearts.

Further Reading

Kaplan, R. and S. Kaplan. 1989. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rashid F. and S. Daga. 2023. How Mr Miyawaki broke my heart. The Wire–Science. https://science.thewire.in/environment/how-mr-miyawaki-broke-my-heart/. Accessed on June 12, 2025.

Soga, M., and K. J. Gaston. 2016. Extinction of experience: the loss of human–nature interactions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14(2): 94–101.

Somil D and R. Fazal. 2023. Will the real Miyawaki please stand up? The Wire–Science. https://science.thewire.in/environment/will-the-real-miyawaki-please-stand-up/. Accessed on June 12, 2025.

Sustainability Idea Labs. 2024. Urban leisure Birds + Leisure.

https://sustainabilityidealabs.org/innovation-stories/forest/urban_leisure.php. Accessed on April 18, 2025.