When we think about conservation, plants and animals are often the first organisms that come to mind. This makes logical sense as they are large, visible to the naked eye, and can be easily observed, allowing us to study their populations and understand their roles in their ecosystems. Many are considered charismatic and can evoke an emotional response to their plight—just think of a baby elephant or a panda eating bamboo. Or picture a sea turtle stuck in a fisherman’s net or seaweed suffocated by plastic debris. Who wouldn’t want to save them?

What about organisms we can’t easily see or observe? Like soil microorganisms. At the base of the soil food web, they are essential to supporting biodiversity and nutrient flow within ecosystems. Given their microscopic size, they often remain neglected. And we typically only hear about microbes in relation to disease or illness. This raises two questions: do soil microbes need conservation, and how would we even know? It’s not as straightforward as referring to the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, because microorganisms are rarely included in such assessments.

In this article, let’s look at why conservation of soil microbes is important (spoiler alert—it has to do with the ecosystem functions they perform!).We’ll also cover how microbiologists look at microbial diversity and its drivers, the impacts of climate change on soil microbial communities, and what we should do to preserve this important group of organisms.

No small feat

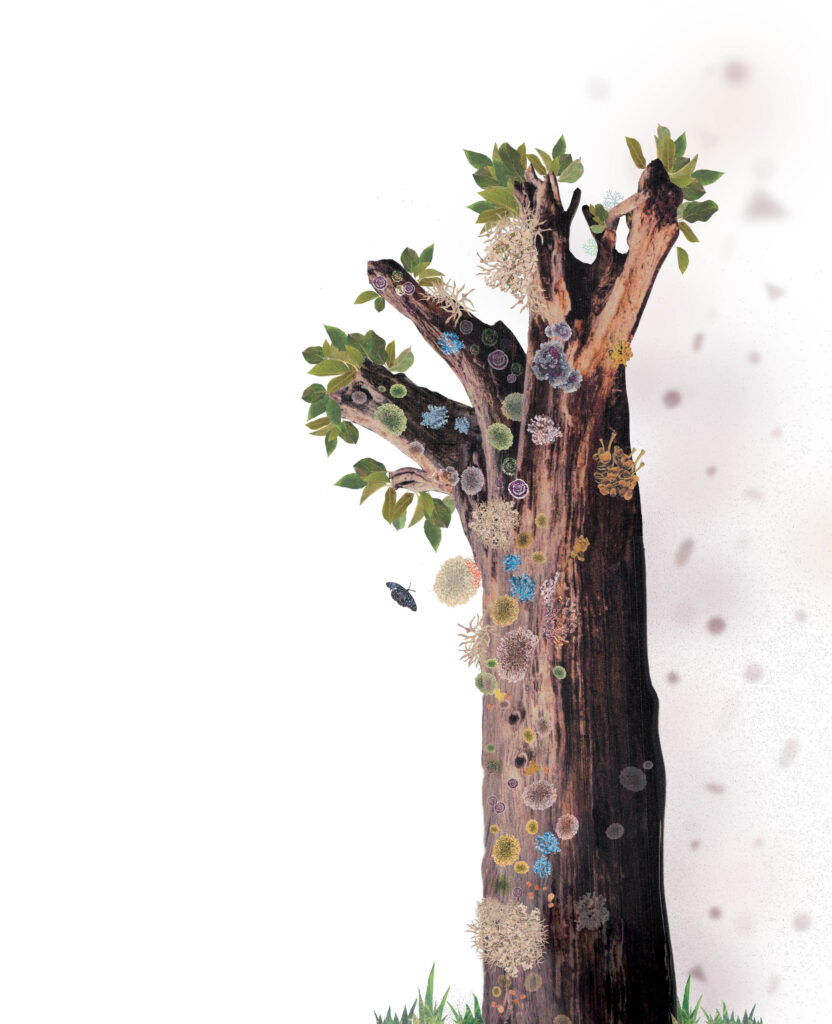

Although invisible to the naked eye, soil microbes play a crucial role in our ecosystems. These microbes—bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses—are crucial for nutrient cycling. For example, if a tree dies, fungi and bacteria are largely responsible for breaking down organic compounds present in the wood (such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose), so that carbon is released back into the ecosystem. Without them, our world would be full of dead plant tissue that would not decay effectively.

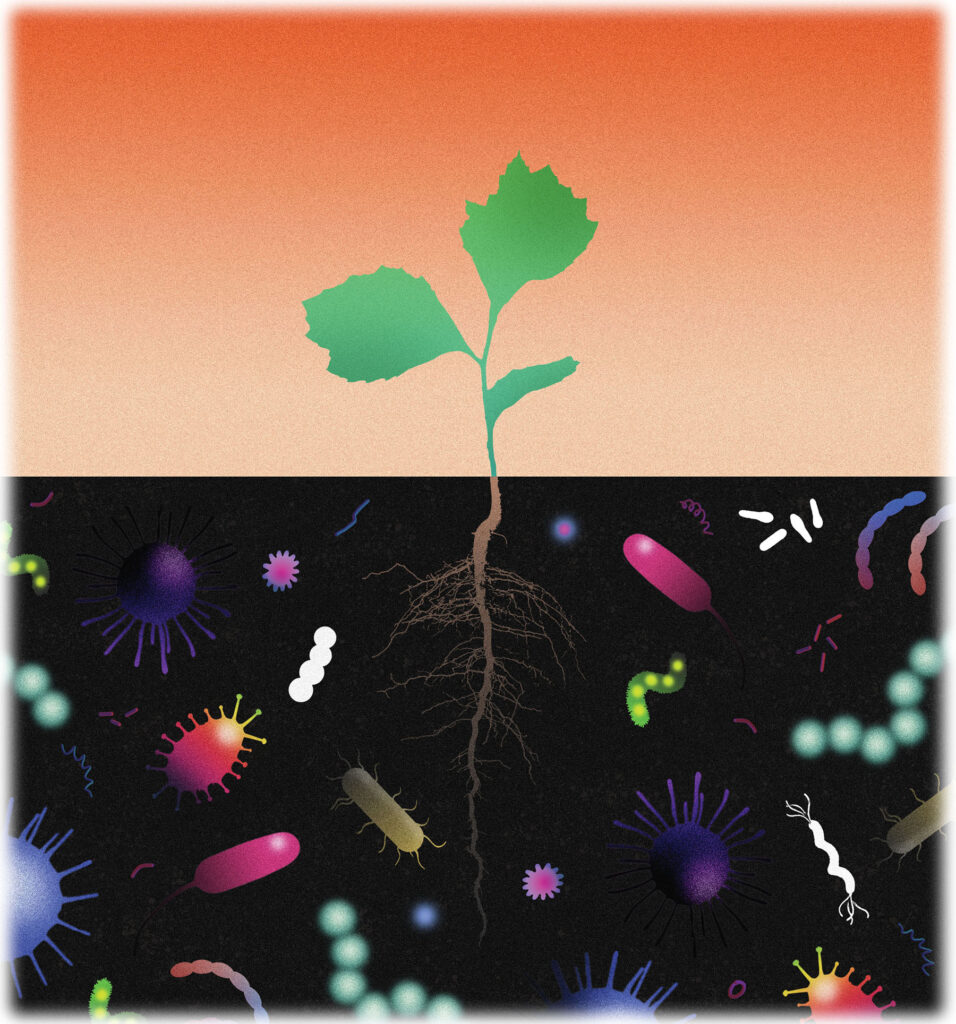

Besides carbon, soil microbes also play a key role in nitrogen cycling. Nitrogen is essential for plant growth and is used to make chlorophyll, proteins, the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), and other compounds needed for growth and development. Nitrogen in the air cannot be used by plants until it is converted to ammonia, which plants are able to absorb through their roots. There are free-living and plant-symbiotic bacteria in soil that perform this conversion, called nitrogen fixation. In fact, one of the most wellknown and agriculturally important relationships between plants and bacteria is found between leguminous plants (such as soybeans, chickpeas, alfalfa) and nitrogen-fixing bacterial symbionts.

These are just two examples of the important roles soil microbes play in ecosystem functioning. There are many more, and they are dependent on the vast diversity of microbes found in soil. Unfortunately, this diversity is being impacted by the same factors responsible for the global decline in biodiversity that we see today, such as land use change and climate change.

Quantifying diversity

To know if organisms should have a conservation plan, we need to know a few facts. These include understanding their ecological roles and populations, and the possible impacts if there is a change in their population size. So how do we collect this information? Before the advancements in DNA sequencing technology, this task was quite challenging. To determine the variety and abundance of microbial species in a soil sample, microbiologists had to depend on isolating pure cultures of the microbes found in soil. However, it is estimated that only about 1 percent of microbes can be cultured, which means this method did not provide a complete understanding of microbial life in the soil.

Fortunately, with advances in DNA sequencing technology, it became easier to sequence genes that help identify microbes as well as their functional genes. Functional genes encode proteins that provide clues about the ecosystem functions provided by the microbial community. For example, if DNA from a soil sample reveals many copies of a gene for the protein that converts atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia, we can predict that the microbial community includes members that are part of the nitrogen cycle, thereby supplying a nitrogen source for plants.

But despite the ease of using sequencing to explore microbial species and functional diversity (traits in a community that influence how the ecosystem functions), there are several challenges. Microbial diversity in soil is incredibly high, requiring statistical models to estimate the total number of species present. A recent estimate suggests that the total number of soil bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea could range from the millions to trillions. With such numbers, it’s not surprising that there is still much to be explored. In fact, of the soil bacteria alone, only about 3 percent of the taxa present are estimated to have had their genome sequenced.

Diversity versus function

Scientists have found that soil microorganism communities vary based on the ecosystem they inhabit, such as deserts, tropical forests, or grasslands. This is mainly due to differences in the pH levels of these environments. In addition, there are other significant factors impacting community composition, including soil water content, organic carbon content, vegetation type, and oxygen levels.

Microorganism species diversity in soil is lowest in areas with very low or very high pH levels. Low pH soils are typically found in the tropics, the Arctic tundra, and boreal forests. In contrast, high pH soils are common in deserts, drylands, and arid grasslands. The regions known as ‘hotspots’, which contain the highest number of different microorganism species, are temperate habitats with a neutral pH level.

Unlike species diversity, the ecosystem functions performed by soil microbes vary depending on the specific ecosystem in which the community is found. For example, a survey of genes involved in nitrogen cycling showed that pH was not a reliable predictor of the diversity of these functional genes. Instead, habitat type and the amounts of carbon and nitrogen in the soil were more accurate predictors. Biomes with the highest abundance of nitrogen cycling genes include tropical forests and areas with high nitrogen inputs, such as pastures, lawns, and agricultural fields. This observation makes sense as nitrogen inputs tend to be high in human-influenced environments, and tropical forest soils generally have fewer nitrogen limitations compared to soils from other environments.

Climate impacts

So how will soil microbial communities be affected as the planet warms? A study from 2021 provided a global view to examine various scenarios of potential climate and land use changes. A key prediction is that climate change will have a greater impact on microbial communities than land use change. Perhaps this is not too surprising because climate change is happening on a global scale, while changes in land use occur locally.

The study also revealed that in over 85 percent of land-based ecosystems, the composition of soil bacterial communities will become increasingly similar. This trend is mainly due to changes in soil pH, which in turn, is linked to the changes in precipitation, temperature, and a reduction in vegetation cover that comes with a warming climate. These results are concerning because greater similarities in microbial communities can lead to reduced variability in their functional genes. And this decline in genetic diversity may cause challenges for microbial communities to adapt to a changing climate and perform essential functions needed for maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

In addition to a loss of genetic variability, the composition of soil microbial communities is predicted to be altered due to climate change. These changes will affect the functions that these communities provide. In fact, in many climate change scenarios, it is anticipated that soil microbes will release more carbon dioxide through the increased decomposition of organic matter. This will result in less healthy soils as they will lose organic carbon. To make it worse, this sets up a positive feedback loop: the release of more carbon dioxide contributes to rising temperatures, which in turn creates conditions that cause even more carbon to be lost over time.

The way forward

To conserve soil microbial communities, we must preserve the substrate they live in by establishing specific soil conservation targets when designing policies. While we have made progress in identifying soil microbial diversity and ecosystem function ‘hotspots’, there are still gaps in our understanding. Further research is needed to refine predictive models so that governments and conservation organisations have the information needed to make informed decisions.

Current studies on hotspots of soil microbial diversity and ecosystem functions indicate that these two types of hotspots do not always coincide. Therefore, both should be taken into consideration in conservation strategies. Additionally, ongoing land use change and climate change will impact microbial communities, potentially changing the locations of diversity and ecosystem service hotspots over time. This must also be considered when developing strategies.

Although there is much work to be done, we have made significant progress. We can maintain this momentum by continuing to expand our knowledge of soil microbe communities and encouraging government agencies and conservation groups to use that knowledge for incorporating soil conservation targets into their policy and conservation plans.

Further Reading

Guerra, C. A., M. Berdugo, D. J. Eldridge, N. Eisenhauer, B. K. Singh, H. Cui, S. Abades et al. 2022. Global hotspots for soil nature conservation. Nature 610(7933): 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-022-05292-x.

Guerra, C. A., M. Delgado-Baquerizo, E. Duarte, O. Marigliano, C. Görgen, F. T. Maestre and N. Eisenhauer. 2021. Global projections of the soil microbiome in the Anthropocene. Global Ecology and Biogeography 30(5): 987–999. https://doi. org/10.1111/geb.13273.

Jansson, J. K., and K. S. Hofmockel. 2019. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nature Reviews Microbiology 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41579-019-0265-7.