We summarise research carried out in Namaqualand in South Africa, that identifies the discrepancies between rhetoric and practices in conservation. The research points at an on-going conflict between conservation and redistribution of land, and how the financially more powerful conservationists tend to win this competition. Finally, we report on how the critique was received by conservationists in South Africa and in Norway in the form of personal attacks and attempts at intimidation.

Over half of South Africa’s 44 million people live in poverty, with almost 70 per cent of the poor living in rural areas. It is well known that colonialism and apartheid resulted in Africans being dispossessed of land on a large scale and confined to overcrowded reserves or Bantustans. After the establishment of the new democratic South Africa in 1994, land reform was therefore seen as a key tool to fight poverty and injustice.

Namaqualand is a semi-arid area in the Northern Cape Province comprising of about 48,000 sq. km. and 70,000 inhabitants. The population consists of people of Nama identity, people of mixed descent, and a minority of European origin. Following the settlement of Europeans during the early part of the eighteenth century, Namaqualand was annexed to the Cape Colony between 1798 and 1847. The resulting land dispossession largely compromised the livelihoods of nonwhites and confined them to mission stations, which acted as places of refuge. The mission stations later became centres of ‘coloured reserves’, which served as reservoirs of labour for mining and farming in the area. These reserves, which today are labeled ‘communal areas’, constituted about 23 per cent of Namaqualand’s area prior to land reform, while about 400–450 white commercial farmers owned almost 52 per cent of the land. Today, about 30,000 people live in Namaqualand’s six communal areas. One third of thepeople of Namaqualand engage in small stock farming. They continue to feel strongly about the loss of their ancestral land, and they are keen to increase their land base.

Natural scientists point out that Namaqualand contains more than 3,500 plant species, 25 per cent of which are endemic to this area, and that it is one of only two internationally recognised dryland biodiversity hotspots in the world. Eager to protect this biodiversity against indigenous use, scientists and conservationists have for a long time maintained that livestock farming, as historically and currently carried out by the people in communal areas, is a threat to this biologically important environment.

However, in view of Namaqualand’s history of racial and social injustice, Benjaminsen et al. (2006) argue that it is ethically problematic to privilege conservation of a maximum level of biodiversity and one particular perception of the ideal landscape at the expense of livelihood security and poverty alleviation. It is also problematic because it presents the private ranch system as an ideal one, without considering disparate production goals and unequal economic opportunities and constraints. Benjaminsen et al.(2006) also present historical evidence demonstrating that rangelands in the area are capable of sustaining livestock densities far greater than those recommended by the Department of Agriculture, which uses ‘commercial’ ranches as a reference model and refers to maximum meat production as the livestock keeping objective. In fact, for most farmers in communal areas, livestock keeping is but one of several livelihood sources, which often will encompass wage labour, remittances, pensions, and social security grants. Some of these sources are insecure, and livestock keeping represents a safety net against fluctuations in other incomes – as a ‘bank account’ that they can dip into to make up for regular seasonal shortages or when other sources fail (Benjaminsen et al. 2006). Namaqualand’s communal livestock farming sector thus has multiple production objectives: milk and meat are important elements in household food security; sheep and goats provide capital storage, insurance, and cash income; and donkeys provide draft power for transport and crop operations. In line with conservationist conclusions about the value and potential threats to Namaqualand’s biodiversity, environmentalists during the last ten years have been mobilising resources for protected area expansion as well as a range of other conservation initiatives. But the problem for local communities is that within the framework of market-based reform, these initiatives tend to compete with redistribution of land to these communities. This tension or trade-off between Western style conservation and support to the livelihoods of marginalised communities was the focus of research published by Benjaminsen et al. (2008).

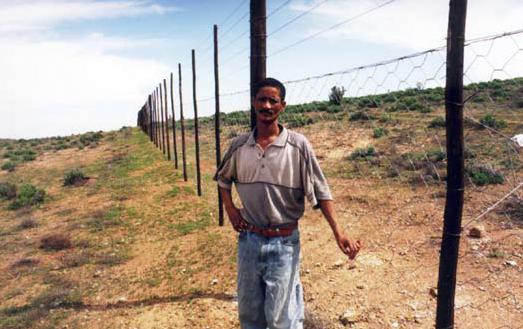

In particular, the research focused on the creation and expansion of the Namaqua National Park. The park was established in 2002 as a typical ‘fortress’ park and it is said to be one of the fastest expanding parks in the world. The purchase of land to create and expand the park has been funded primarily by wealthy South Africans (the industrialists Leslie Hill and Anton Rupert) through a fund managed by WWF-South Africa. The expansion of the park directly outcompetes land reform in the area by the conservation fund being willing to pay far above the market price. The result is that landless neighbouring communities remain landless or with very little land. In addition, the community conservation rhetoric is used in the park’s presentation of itself. A ’rhino-proof fence’ has for instance been erected around the park as part of the park’s ’empowerment project’. The park also claims that its ’empowerment of local people and institutions has been enormous’. Its main contribution to this ’empowerment’ seems to be environmental education leading to ’demonstrable improvements in the attitudes of local communities towards conservation as a justifiable form of land use’. Based on an early draft of Benjaminsen et al. (2008), a network of conservationists and natural scientists reacted strongly already in 2005 through a series of emails. The purpose was clearly to try and stop the publication through intimidation of its authors. Simultaneously, we had a discussion with WWF-Norway in Norwegian media. Our main argument was that there is a gap between rhetoric and practice in conservation work in Africa.

In this debate, we were also using the example of Namaqua National Park. Our critique of WWF caused WWF Norway to make strong personal attacks on us instead of involving in a constructive debate. They also contacted the directors of our research institutes in order to try to force us through silence. Why are some conservationists reacting in this way to critique? As Chapin (2004) has shown, big conservation organisations have increased their funding and power tremendously since the 1990s. This increase is due to a highly successful fundraising campaign among businesses, governments in rich countries and wealthy individuals. To sustain this powerful position, big conservation organisations spend large amounts of money on public relations. Critique is therefore a threat to the glossy picture presented and hence to the financial and administrative expansion of the organisations and the particular type of conservation they represent. Conservationists may find it legitimate to neglect principles of ethics and transparency in order to pursue their goals. This type of strategy may, however, in the longer term have adverse effects not only on local people’s livelihoods, but also on environments.

References:

Benjaminsen, T.A., R.F. Rohde, E. Sjaastad, P. Wisborg and T. Lebert. 2006. Land reform, range ecology, and carrying capacities in Namaqualand,

South Africa. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96(3): 524- 540.

Benjaminsen, T.A., T. Kepe and S. Bråthen. 2008. Between global interests and local needs: conservation and land reform in Namaqualand, South Africa. Africa 78 (2): 221-244.

Chapin, M. 2004. A Challenge to Conservationists. World Watch November/December: 17-31.