From the parking lot, there is nothing special about this isolated patch of greenery on the outskirts of Mysore, three kilometres from the quaint temple town of Srirangapatna. But a closer look reveals a quiet riparian wetland, comprising six islands and six islets on the banks of the mighty Kaveri River.

The Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary, sprawling over 67 hectares of protected land, is the oldest bird sanctuary in Karnataka and one of India’s first sanctuaries. The islets of Ranganathittu formed when an embankment was built over the Kaveri river between the years 1645 and 1648. The wetland was declared a protected area (PA) in 1940 by the King of Mysore under the insistence of esteemed ornithologist Salim Ali, who noticed that high numbers of birds arrived at Ranganathittu to nest on the islets. In 2017, an eco-sensitive zone of 28.04 sq. km. was declared around the PA, disallowing commercial activities without government permission.

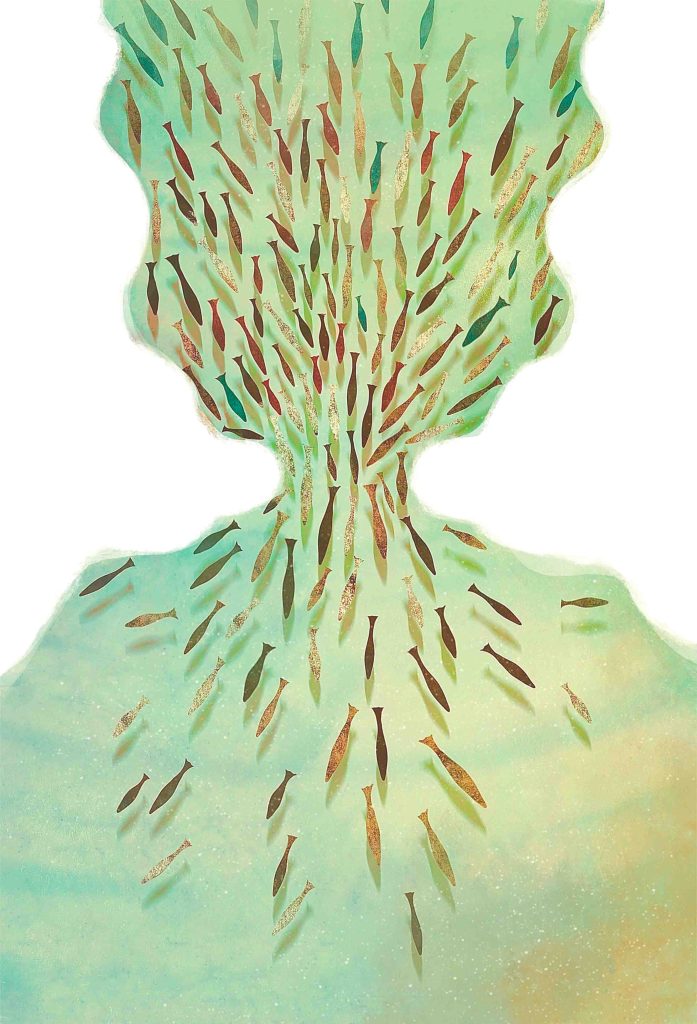

When we last visited Ranganathittu, in February 2018, the islets were densely packed with nesting birds, so thickly crowded together that we could not sight the trees upon which the birds had built their nests. Their mingled cries filled the air, deafening us and forcing us to shout to be heard above the cacophony. Mugger (marsh) crocodiles basked on the sunny rocks protruding from the water, their young clambering clumsily onto their scaly backs as tourist boats drew nearer for prime photo opportunities. The avian life was particularly thrilling; we spotted painted storks, Asian openbill storks, Eurasian spoonbills, Oriental darters (snake bird), spot-billed pelicans, black-crowned night herons, black-headed ibises, cormorants, brilliantly-coloured kingfishers, and even river terns, which nest in Ranganathittu during peak winter season.

The main island is also a birder’s paradise; we spotted the Tickell’s blue flycatcher, the Indian grey hornbill, the Asian paradise flycatcher, and a spot-breasted fantail that danced about like a little peacock spreading its wings and tail. In 2007, birders sighted a lesser frigate bird nesting in Ranganathittu, a rare event indeed! At home over the ocean, frigate birds are swept over India’s coasts during storm events or gusty monsoon winds. Over 40,000 birds spanning nearly 222 species were recorded at this sanctuary during the winter months (December through February) over the past decade, so our visit coincided neatly with that of migratory birds from different corners of the globe. Signage at the park informed us that certain species migrated from as far as Siberia and Latin America!

Ranganathittu is classified as a riparian zone in the Indomalaya ecozone, a result of its unique blend of land and water. Despite its location along the majestic Kaveri, the sanctuary has faced occasional drought events due to an erratic monsoon, leading to a dip in bird populations in the PA. During the monsoon, the PA receives heavy flooding as water is released from the Krishnaraja Sagar Dam, 8 km upstream on the Kaveri River. Portions of the islets are permanently damaged due to repeated flooding, yet remain valuable habitat for birds and wildlife. According to the eBird database, there are records of sighting threatened species such as the Indian spotted eagle, the tawny eagle and even the endangered Egyptian vulture here. The islets are home to multiple colonies of flying foxes, bonnet macaques, palm civets, grey mongoose, and even smooth-coated otters. The islets are home to diverse flora; Terminalia arjuna (the Arjun tree), Syzigium cumini (the

Jamun tree), bamboo, and various broadleaf species make their home here. The banks are coated in riverine reed beds, which create habitats for fish, molluscs, and invertebrates, as well as for ground-nesting birds. The soil along the river is soft and loamy, ideal for aquatic insects. The sanctuary is also surrounded by vast stretches of irrigated agricultural fields where aquatic insects are available in plenty. An abundance of these insects attracts numerous birds to the sanctuary.

Given its location on the Bangalore-Mysore highway, only 18 km away from Mysore, this sanctuary attracts more than 100,000 visitors annually. Most tourism packages in Mysore include Ranganathittu, and it is the most-visited sanctuary (without charismatic species) in India. On average, the sanctuary used to receive about 700 tourists in a day, both domestic and foreign. It is also open year-round unless a crisis such as monsoonal flooding, and now, the pandemic, occurs. During our visit, we each paid Rs. 70 as entry fee (foreign nationals will have to pay five times this price) and Rs.100 for our DSLR cameras. There is an interpretation centre inside the sanctuary with informative games and trivia on the bird species found at the sanctuary, for children and adults alike.

While increasing tourism has a positive impact on the economy, it is yet to be studied whether there are resultory ecological impacts on the birds and river ecosystem. After a long hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the monsoon, the sanctuary opened to tourists on September 1, 2020. While tourist numbers are still low, people are increasingly venturing outdoors to escape the city and tourism will likely rise rapidly. This riparian sanctuary gives hope for the takeoff of bird watching-based tourism in other areas given that it is comparatively cheap and easily accessible to tourists. Additionally, efforts are ongoing to list this site as a RAMSAR wetland; the RAMSAR convention decrees that a wetland must meet one of nine criteria to be listed and Ranganathittu meets three. With its avifauna and protected riparian habitat, Ranganathittu remains a birder’s paradise and a gem in Karnataka’s crown of natural wonders. We hope to hear of its uplisting to RAMSAR in the near future.