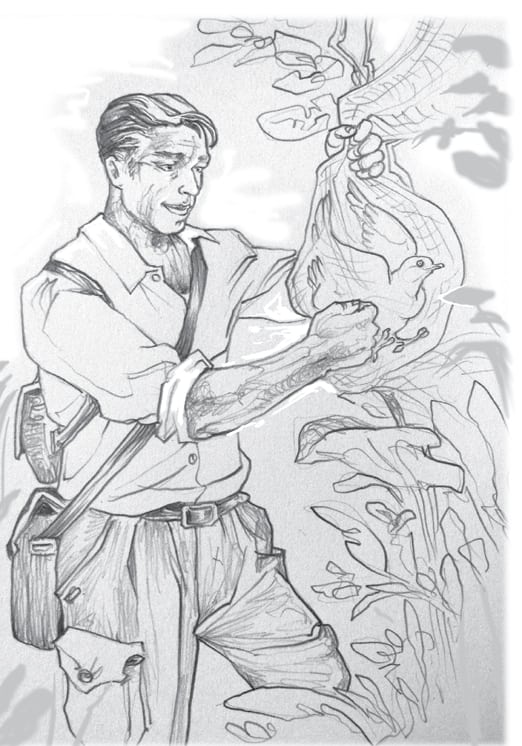

Reginald Innes Pocock was a British naturalist, who is today considered one of the most important mammalogists connected with India. Born on March 4, 1863 in Bristol, England, Reginald Pocock was the fourth son of Rev Nicholas Pocock and Edith Prichard. As a child he had varied interests; he was athletic and played rugby, lacrosse and lawn tennis. He was fond of poetry and was a skilled artist. He also showed keen interest in animals and frequently visited the Zoological Gardens at Clifton where he learned about keeping and breeding mice, lizards, turtles and other smaller animals.

THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM

As his interest in zoology grew, he went on to study biology and geology at University College, Bristol. His education made him ideal for an Assistantship at the Department of Zoology at the British Museum (Natural History) now known as the Natural History Museum in London. The position involved mainly organising the Museum’s zoological specimens and describing those that were unidentified. After a brief stint arranging British birds in the public gallery, Pocock moved to the Entomology section where he took over the arachnid and myriapod collections, becoming a recognised authority on these groups. His stint with the Zoological Society museum substantially increased its entomological collections. He worked at the museum for the next 18 years, publishing over 200 papers, including a special volume on Arachnida for the Fauna of British India series. He also contributed several of his own illustrations to his papers, enhancing their aesthetic value.

INTEREST IN MAMMALS

While still at the Entomology section in 1897, Pocock came across a zebra like specimen in the museum simply labelled Quagga. Curious about the taxonomical affinities of the animal, he examined it and came to the conclusion that it was closely related to the plains zebra Equus quagga found throughout East Africa. The animal, extinct by the time Pocock came across it, featured in his first paper on mammals, ‘The species and subspecies of Zebras’. Soon after this, Pocock helped Dr P L Sclater, Secretary to the Zoological Society of London (1860-1902), finish the remaining chapters of the Book of Antelopes, co-authored with Dr Oldfield Thomas, Pocock’s colleague who headed the section on mammals at the museum. This helped him develop a better understanding of mammals. He then made trips to the Balearic Islands of Spain with Oldfield Thomas to collect mammals, arachnids and myriapods. This trip further spiked his interest in mammalogy leading to the publication of several papers in Nature during this period. So great was his interest that when fellow naturalist R C Wroughton, who was then interested in studying arachnids, approached him for help, Pocock advised him to instead turn his attention to studying mammals.

CONTRIBUTIONS TO MAMMALOGY

Having decided to focus on mammals, Pocock was eager to move to the mammalian section of the Museum. However no position opened up for him and in March 1904, he resigned from his assistantship at the museum to become the Superintendent of the Zoological Gardens at Regent’s Park, which held a curious connection to his past; the quagga specimen that first drew him to mammals was housed there when it was alive. Although the position mainly involved administrative duties, Pocock spent considerable energy trying to improve living conditions for the captive animals. Here, his experience from childhood days spent at the zoo in Clifton came in handy. He also started collecting skins and skulls of dead animals at the zoo, and realised the importance of external features such as ears and hooves, which most animal collections lacked, for accurate identification of species. He went on to thus pioneer the use of external morphological characters for classifying mammals.

During this period, Pocock also worked on a revision of the genus Cercopithecus, Old World monkeys from Africa and on digestive systems in ruminants. He wrote a series of papers on carnivores, such as ‘The Jackals of SW Asia and SE Europe’, from 1914 till the time of his death. These works earned him a reputation as an authority on mammals. His specialty was considered ungulates, carnivores and primates, with notable writings on the external characters of Artiodactyla or eventoed ungulates such as pigs, deer and antelopes; the classification of felids and mongooses and the external characters of Madagascar-restricted lemurs and South American monkeys.

INDIAN MAMMALOGY

In 1923, after nineteen years, Pocock resigned from his post at the Zoological Gardens to dedicate the rest of his life to the study of mammals. He went back to the Natural History Museum as a ‘temporary scientific worker’, a voluntary position. His second stint at the museum marked a period of great advances in Indian natural history. Pocock became a regular contributor to the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, and wrote several important papers describing langurs or leaf monkeys, Asiatic lions, leopards and civets.

His greatest contribution to Indian mammalogy was perhaps the Mammalia volume of the second edition of Fauna of British India series in 1939. In this revised edition, he highlighted a new more systematic approach to mammalogy based on a method devised by American naturalist C Hart Merriam. Pocock pointed out the inadequacies in the first edition of Mammalia produced nearly 50 years prior by W T Blanford, where specimens (mainly skins) were often poorly preserved and rarely accompanied by details of their geographical origin. Using the new approach that involved collection of entire animals and notes on location, altitude and date of collection (all common practices now), mammalogists were able to identify whether an animal was indeed a new species or merely a sub species or race that showed minor variation in morphology due to its local environment. The trinomial system of nomenclature was also introduced in this new edition by Pocock. Using this method he pointed out that Blanford had for instance classified the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes montana) found in the Himalayas and Desert Fox (V v pusilla) as two distinct species when they were merely sub species of the common fox (V vulpes) that showed morphological variations. Using this new method he examined minor variations in skulls and skins of forty specimens of felids previously classified as five distinct species and concluded that they were subspecies of the wildcat Felis silvestris. The taxonomy of the species however continues to remain in flux. While the International Union for Conservation of Nature only recognises four sub species, Mammals of the World (third edition, 2005) the standard reference guide by Wilson and Reeder recognises twenty two subspecies.

Pocock continued to work till the day before his death on 9th of August 1949, at the age of 86. At the time of his demise, he was involved in the compilation of a systematic monograph of Felidae, the Catalogue of the Felidae in the British Museum, and a description of the external characteristics of rare mammals, such as the endangered one-horned rhino Rhinoceros unicornis, from the Indian sub-continent. He described over 85 species of extant mammals from around the world and inspired several other naturalists to take up the study of mammals.

Suggested reading:

Reginald Pocock. The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma – Mammalia Vol. 1 (1939) and Vol. 2 (1941). (London, Taylor and Francis, 1939, 1941).