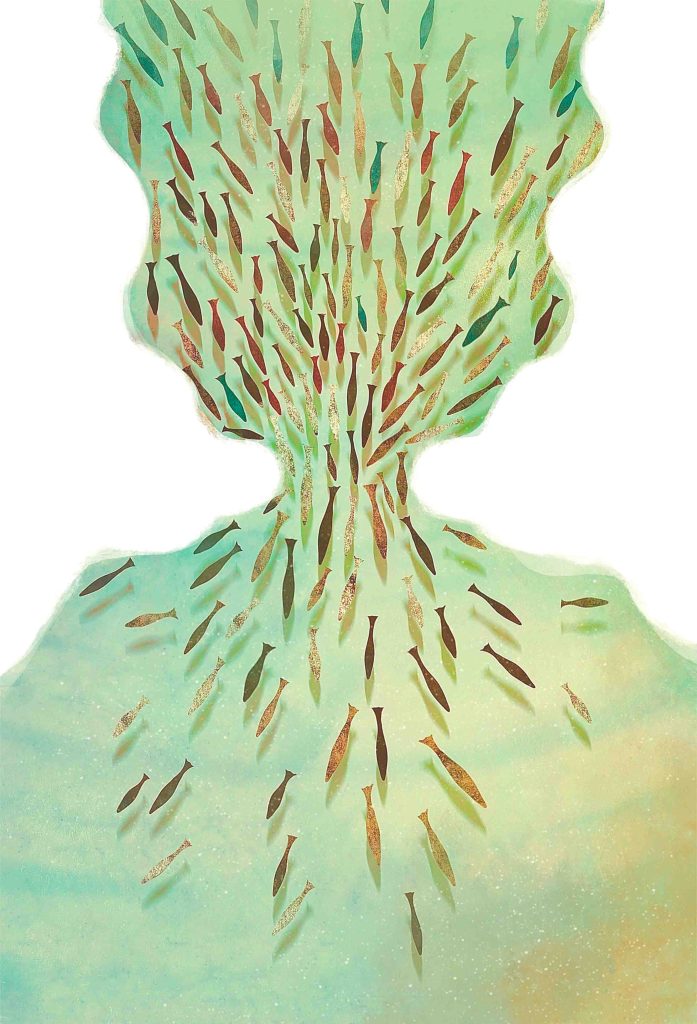

We have all heard of sharks. When you imagine one, the typical picture that might come to your mind is a large, grey-white fish with pointed fins and sharp, deadly teeth. Now imagine something like a shark, but with a flattened head and torso, pointed snout and brown body, and you get a rhino ray, the strange-looking and ancient relatives of sharks. Named because their pointed snouts apparently resemble rhino horns, these species are cartilaginous fish that evolved from sharks and form a link between sharks and rays. Rhino rays are made up of different families, including guitarfish (Glaucostegidae), wedgefish (Rhinidae) and sawfish (Pristidae). Their flattened bodies are an adaptation for life on the seafloor—they are often found swimming close to the bottom, or resting in the seabed, concealed and camouflaged in sediment.

On the edge of extinction

Rhino rays have been increasingly in the spotlight in recent years, and not for good reasons. Sadly, research has found they are currently one of the most threatened groups of species in the world. All but one species of guitarfish, wedgefish and sawfish are Endangered or Critically Endangered. These species are found in shallow coastal waters, overlapping with some of the most intense coastal fisheries in the world. Their fins are highly valuable, fetching at least twice the price of shark fins, which drives fishers to target and catch them.

In other cases, they are caught accidentally as ‘bycatch’ and then retained by fishers to sell or consume. These factors have pushed rhino rays to the edge of extinction, even more so than other rays and sharks. Rhino rays are ‘bioturbators’, excavating and modifying the ocean sediments and habitats. As meso predators, they also form important links between species at the top and bottom of the food web. These essential ecological functions could be lost if rhino rays disappear.

Despite the risks they face, rhino rays remain a data-limited species, which means we know very little about them, especially in countries such as Indonesia and India where they are the most fished. Studying any marine species is challenging, but rhino rays can be particularly elusive despite being found in shallow waters. They were also overlooked for a long time, with their more charismatic cousins— sharks receiving most of the attention from research and conservation.

Despite the risks they face, rhino rays remain a data-limited species, which means we know very little about them, especially in countries such as Indonesia and India where they are the most fished. Studying any marine species is challenging, but rhino rays can be particularly elusive despite being found in shallow waters. They were also overlooked for a long time, with their more charismatic cousins—sharks receiving most of the attention from research and conservation.

The guitarfish of Goa

“It’s a super rare fish, but you can see it on the shore. If you see it on the shore, it means your stars are aligned and you are very lucky,” says a gillnet fisher in Goa.

Goa, on the west coast of India, is known for its beautiful beaches, blue waters, tourism and seafood. Rhino rays might be the last thing on your mind if you travelled there—indeed, most tourists who visit have probably never heard of them. But species such as the widenose guitarfish (Glaucostegus obtusus) and sharpnose guitarfish (Glaucostegus granulatus) are found along Goa’s coastline, sometimes inhabiting waters that are only ankle-deep!

I have been working in the field of fisheries and shark research since 2018 and have surveyed hundreds of dead rhino rays captured in fishing vessels. It was in Goa that I had my first live sighting of one species the widenose guitarfish. I was on a quiet beach at sunset, when a number of them came into the shallow waters, moving in and out with the waves. Seeing these Critically Endangered species swimming at my feet was an experience I’ll never forget. These encounters led me to study rhino rays, especially guitarfish, in Goa for part of my PhD research.

Given that scientists know almost nothing about these species in this region, fishing communities can be the best source of information. The lives of fisherfolk are intertwined with the sea, and they hold a wealth of knowledge accumulated over generations. Our study has documented the local ecological knowledge (LEK) that fishers in Goa hold about rhino rays, to better understand their habitat use and seasonality, the kind of threats they face and how people can conserve them. We also looked into their interaction with fisheries—how they were fished, how they were used, and what kind of value they have for fishing communities. We plan to use these insights and knowledge on rhino rays to understand how to conserve them.

“It’s a super rare fish, but you can see it on the shore. If you see it on the shore, it means your stars are aligned and you are very lucky” – A gillnet fisher in Goa

A day in the research life

With my degree in marine biology, people often assume that I spend most of my time underwater exploring the frontiers of the ocean. The reality is very different; most of my fieldwork involves spending time in fishing centres, monitoring catch, and engaging with local communities. For this research on guitarfish, a typical day in the field involved visiting one or multiple fishing sites and interviewing local fishers about guitarfish, sharks, and issues about marine sustainability. In total, we visited and sampled 20 different fishing villages and harbours in Goa. Some of these were tourist beaches, others were more isolated and sometimes quite challenging to get to.

Some fishers were enthusiastic to speak to us about ‘Ellaro’ or ‘Kharra’, as guitarfish are called in Konkani (the local language) and had numerous stories to share. Others couldn’t understand why we were interested in this ajeeb machli (strange-looking fish), as one fisher put it.

Conducting interviews and working with communities is not always easy; people can be suspicious and unwilling to speak, sometimes interviewees may lie (with good intentions) to give you the responses they think you want, and conversations can often take unexpected turns. But it can be a very rewarding process overall. The knowledge and experiences that some fishers have are unlike anything you could read in a textbook or scientific paper, and it can be a pleasure to document them.

Feeding time

Why do guitarfish come to such shallow waters? We suspect that many of these beaches, especially around river mouths, form nursery grounds for guitarfish, where females come to give birth to their young. Guitarfish, like many sharks and rays, are ‘viviparous’ or livebirthing, which means they give birth to a small number of young (called pups) and don’t lay eggs. Shallow, sheltered beaches near estuaries and rivers can form ideal habitats (nursery grounds) for the pups, because of the abundance of food and protection from predators.

Given their importance in the life cycle of guitarfish and other rhino rays, these habitats should be protected. However, in many parts of the world, these shallow estuarine habitats are facing severe disturbance from development, fishing, and other human activities.

In Goa, fisher knowledge has helped us identify the types of habitats and regions that guitarfish are found in (sandy seafloors near river mouths), and their seasonality (found most often during and right after the rains). Fishers also confirmed that they had seen small guitarfish feeding on crabs and molluscs in the shallow beach waters. We have broadly mapped the potential nursery sites and other essential habitats for guitarfish, and through further research, we can identify the areas that need to be prioritised and protected.

Communities and conservation

Alarmingly, fishers reported that not only sawfish but also wedgefish appear to be severely declining or even vanishing from this region. “We call this fish Anshi,” an older fisher remarked when I showed him a picture of a sawfish. His younger crewmates had not seen this species before and didn’t recognise it. “I haven’t seen this fish in at least 20 years. It’s gone from our waters”.

This isn’t the case for guitarfish, which continue to be fished in Goan seas. Fishers catch them as bycatch in all types of fishing gear, most often small-sized individuals (juveniles), which are considered to have low economic values and are used only for local consumption. In fact, more than half of interviewed fishers would discard the fish back into the water, dead or alive, if they were too small or they had caught too many.

When we spoke to them about the protection of guitarfish and other rhino rays, fishers’ attitudes seemed to support conservation.

“We don’t get them much, and don’t really sell them much, so if catching this fish is banned, it won’t make a difference to us,” a gillnet fisher told us.

All the fishers we interviewed stated that they may be willing to participate in conservation measures for rhino rays, which is a very positive finding. One young fisher explained, “If catching the guitarfish is banned, we can just release them back into the water and they will swim back to wherever they like to live. They stay alive for a long time even after we catch them, so they will be fine.”

At the time of this study, all species of guitarfish were legally permitted to be fished and were not protected. However, with recent changes in legislation, the wide nose guitarfish has been listed as protected, along with a few other rhino ray species. Our findings suggest a pathway for this legislation to be implemented in regions like Goa—where the rhino rays form low-value bycatch, live release measure through community participation would likely be more effective than top-down sanctions. Local knowledge of fishers will be essential to designing effective and fair conservation plans.

If guitarfish can be protected locally or regionally in places like Goa, then these sites could become sanctuaries for these highly threatened species. These small-scale successes could spell hope for the future and help save the guitarfish from becoming the next sawfish.

Further Reading

Kyne, P. M., R. W. Jabado, C. L. Rigby, Dharmadi, M. A. Gore, C. M. Pollock, K. B. Herman et al. 2020. The thin edge of the wedge: Extremely high extinction risk in wedgefishes and giant guitarfishes. Aquatic conservation: Marine and freshwater ecosystems 30(7): 1052–7613. doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3331.

Gupta, T., E. J. Milner-Gulland, A. Dias and D.Karnad. 2023. Drawing on local knowledge and attitudes for the conservation of critically endangered rhino rays in Goa, India. People and nature 5(2): 645–659. doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10429.

Acknowledgement:

This research was conducted by Trisha Gupta, EJ Milner Gulland, Andrew Dias, and Divya Karnad, and was supported by the Prince Bernhard Nature Fund and the Levine Family Foundation.