What do sea snakes eat? Do different types of sea snakes eat the same things? Do they live in the same places? Do these behaviours change throughout the year? For the past two years I’ve been working in Malvan, Maharashtra, trying to answer these questions. But first there was something I had to figure out: how does one study an animal that spends most of its time underwater? Three words – fishers, boats and nets.

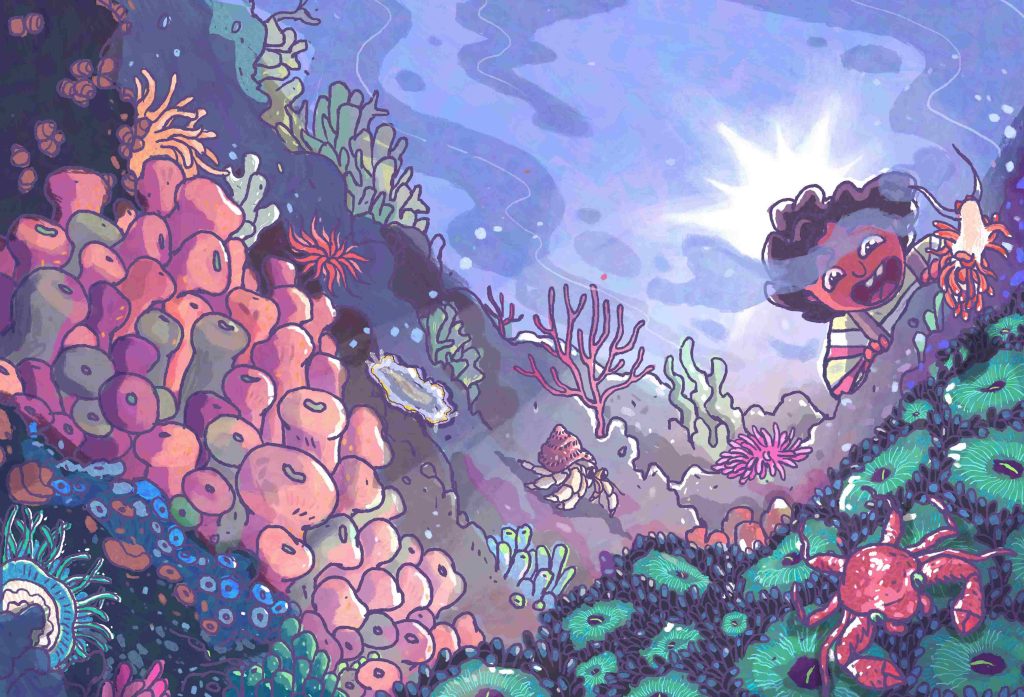

Perhaps before I go any further I should explain what a sea snake actually is. They are unique marine reptiles that evolved from land dwelling ancestors in the waters around Australia, 2 – 3 million years ago. Like all other reptiles

they need to breathe air to survive, but can dive for up to 30 minutes at a time in search of food. Some sea snakes may

come on to land to rest or to lay eggs – these are known as ‘sea kraits’. True sea snakes on the other hand live their

whole lives at sea. To do this, they have evolved to give birth to live young and may have around 20 babies at a time. Sea snakes can be found all the way from Australia in the east to the Eastern Coast of Africa. Throughout this range they frequently come into contact with people. In Malvan, we have found 5 species of true sea snakes, of which the Beaked sea snake and the Shaw’s sea snake are the most common. These are the focus of my work.

Humans have been casting their nets into the oceans in search of food for thousands of years. As the number of people grew, more boats with better nets, lines, hooks and eventually engines began to operate in coastal waters.

While we got better at catching large quantities of the tasty seafood we wanted, our nets would often also bring up other, inedible types of sea-life we hadn’t meant to catch and had no use for. This is known as ‘bycatch’ and it affects scores of marine organisms in coastal areas and oceans around the world. Sea snakes are very often caught as bycatch in fishers’ nets at Malvan, and we don’t know very much about what effect this is having on these marine reptiles.

Every morning the fishers at Malvan set out, while it’s still dark, around 2 am. They return to shore just after dawn, so my project assistant Yogesh and I try to wake up before the sun rises, as this the best time to meet them and see what

they have caught. With our notepads and snake hooks (metal hooks with which we can gently pick up the snakes without being bitten) in hand, we walk along the beach. The fishers start with a bit of black tea then put on plastic overalls and start sorting their catch. Yogesh and I wave at our fisher friends and ask them what they caught that night. Every so often, a fisher will call us over. “Maruza!”, he’ll say, which means sea snake in the local Malvani. We then carefully collect the snake from the net and ask the fishermen for information about where they caught it, what depth the net was at, and what the habitat is like on the sea floor in that area. This helps us understand more about where the sea snakes are spending their time. Sometimes, we may show up late for the catch and then get an earful from the fishers for sleeping in. On average, we get around 3 – 4 snakes each morning.

We then take these snakes back to our field base where we measure them and check their stomachs for food, or eggs if it’s a female snake. We also take blood and scale samples which will tell us about what they’ve been eating and where they’ve been moving over the past few weeks or months. Once we have collected our data, we take the snakes back to the beach and release them into the water.

Through this work, with the help of our fisher friends, we hope to come a few steps closer to understanding how humans and sea snakes interact in their shared environment and how they can live together peacefully.