Early attempts at environmental conservation, as represented in the environmentalism of the 1960s and early 1970s were shaped by deep ecology arguments for the intrinsic value of nature independent of social and economic utility to humans. These values combined with newly recognised ecological risks to produce so-called “fortress conservation”, strategies premised on excluding people and economic processes from protected areas dedicated to nature conservation. The shift away from this position began in the 1970s as public agencies, donors, activists, and researchers confronted socioeconomic, political, and ethical problems linked to displacement of local people in efforts to arrest deforestation, loss of biodiversity, unsustainable fishing, and other resource-extraction practices. The strategies that began to emerge aim to achieve and consolidate conservation gains by promoting secure livelihoods that allow local people to shift away from ecologically unsustainable practices. While there is considerable heterogeneity under this big tent of sustainable development, the relationships between human-centered and nature-centered objectives remain substantially unclear.

We need new approaches to conservation, and we need to reflect critically on the experiments underway. At the Nilgiris Field Learning Center (hereafter NFLC), in partnership with the indigenous communities, we cross boundaries of disciplines, cultures, languages, organisations, scales, and the worlds of theory and practice as we pursue our goals. This is a collaborative project of a mid-sized NGO, Keystone Foundation, based in Kotagiri, Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu, and a large higher education institution, Cornell University, based in Ithaca, New York. Our collaboration aims to create an integrative model of education, research, and practice focused on issues of environmental conservation and sustainable development. The sprawling Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR)—a global ecological diversity and endemism hotspot—provides an ideal setting for this experiment. It contains a broad range of landscapes from protected areas, wildlife sanctuaries, and large tracts of reserve forests to the thriving plantation and commercial agriculture, active tourism industry, and a real estate boom fuelled by India’s economic growth that is reshaping urbanisation in the hills, including towns like Kotagiri. The NBR also contains a great diversity of cultures and communities including more than 30 adivasi (indigenous) groups who, at about 16 percent of the total NBR population of 1.2 million people, are among the region’s poorest and most marginalised. The scale and complexity of challenges and changes we observe in the region provide an ideal setting to develop and test a new model of environmental conservation and sustainable development.

This article lays out a conceptual framework for this boundary-pushing experiment. In the e-edition of Current Conservation, this article is linked to seven research briefs by pairs of NFLC student researchers— an undergraduate student from Cornell working with their partner, a young Adivasi community member from the Nilgiris. The NFLC research projects have been operating for more than 5 years. The briefs highlight aspects of the work students did over 15 weeks in spring 2017.

Connecting conservation to development: three approaches

At the scale of the globe and within the Nilgiris, our analyses of biodiversity, forest health, water resources, waste production, and the human welfare implications of environmental change and economic development indicate the urgent need for both environmental conservation and sustainable development. By many measures, historical processes of ecosystem degradation are not just unchecked, they are accelerating. The cumulative effects of degradation and feedbacks between multiple stressors compound the conservation challenge. The results of existing efforts to mobilise public authority (government), private interests (markets), and collective solidarity (community) to advance conservation are very modest when examined against the scope of the challenge. Against this backdrop, there is a need to think critically, creatively, and pragmatically about conservation and to explore a range of alternatives. Any project of critique and potential reconstruction must encompass both means (i.e. techniques, strategies) and ends (i.e. objectives, goals) of conservation.

Here, we will discuss three popular conservation strategies to highlight the interplay between environmental conservation and sustainable development: Payments for Ecosystems Services (PES), Integrated Conservation and Development Projects (ICDP), and the Biodiversity and Community Health initiative (BaCH).

Payments for Ecosystems Services (PES), schemes that provide financial incentives to secure a range of goods and services humans derive from nature, have emerged as a dominant way to talk about conservation. The PES paradigm is strictly anthropocentric. The mechanism and the justification for securing ecosystems lie in the functional value of nature in relation to human security, wellbeing, and prosperity. Under the logic of PES, the beneficiaries of healthy ecosystems pay for their conservation. For example, downstream cities pay upstream forested communities to conserve water flows and the landscapes on which these flows depend. Over time, PES has become increasingly integrated with efforts to address poverty, and it is now standard practice to identify these initiatives as “pro-poor” conservation schemes.

Explicit engagement with the economics of conservation is also represented in Integrated Conservation and Development Projects (ICDP). Originating in the 1980s, ICDPs are biodiversity conservation programmes that involve an economic development component. By attending to the material needs and livelihoods of local people, these projects seek to restructure linkages between the economic behaviours of local people and the integrity of ecosystems. For example, Keystone Foundation, a core partner in the NFLC, advances livelihoods, enterprise, and environmental conservation through a programme of adding value and retail marketing of non-timber forest products including honey, resin, and spices.

Both PES and ICDP seek to align the economic interests of local actors with environmental conservation objectives. These concepts are part of a larger set of ideas in which environmental conservation and socioeconomic wellbeing are pursued as interdependent and mutually reinforcing objectives under the overarching goal of sustainable development. Despite widespread agreement regarding the need for an integrated socio-ecological approach, we do not have fully developed models to guide investment, interventions, and assessment. More importantly, case studies and reviews of PES and ICDP implementation have highlighted problems in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and equity. For example, these interventions often poorly reflect the interests and ambitions of local people, women in particular. Further, these efforts are difficult to sustain after the initial stream of investment from external funders comes to an end, and it is not clear that these place-based efforts can scale up to produce transformative change. Given the experience to date, we lack solid evidence that these models of an integrated approach can deliver ecological conservation and inclusive economic development at different scales and in a full range of contexts.

Our third example of pursuing integrated thinking is represented by the Biodiversity and Community Health (BaCH) initiative, a consortium of leading global organisations dedicated to achieving the goals of biodiversity conservation and food and health security. This group aims to “leverage … ecosystems and biodiversity as well as knowledge, skills, and capabilities of the populations living in close proximity to biological resources.” They place special emphasis on employing bioresources and traditional knowledge in developing strategies that explicitly bring in a health and nutrition dimension into the environment-development binary. This expanded focus also opens up issues of community engagement and local control over natural resources in different ways, including highlighting the importance of long-term strategies of education and building community awareness of environmental changes and challenges.

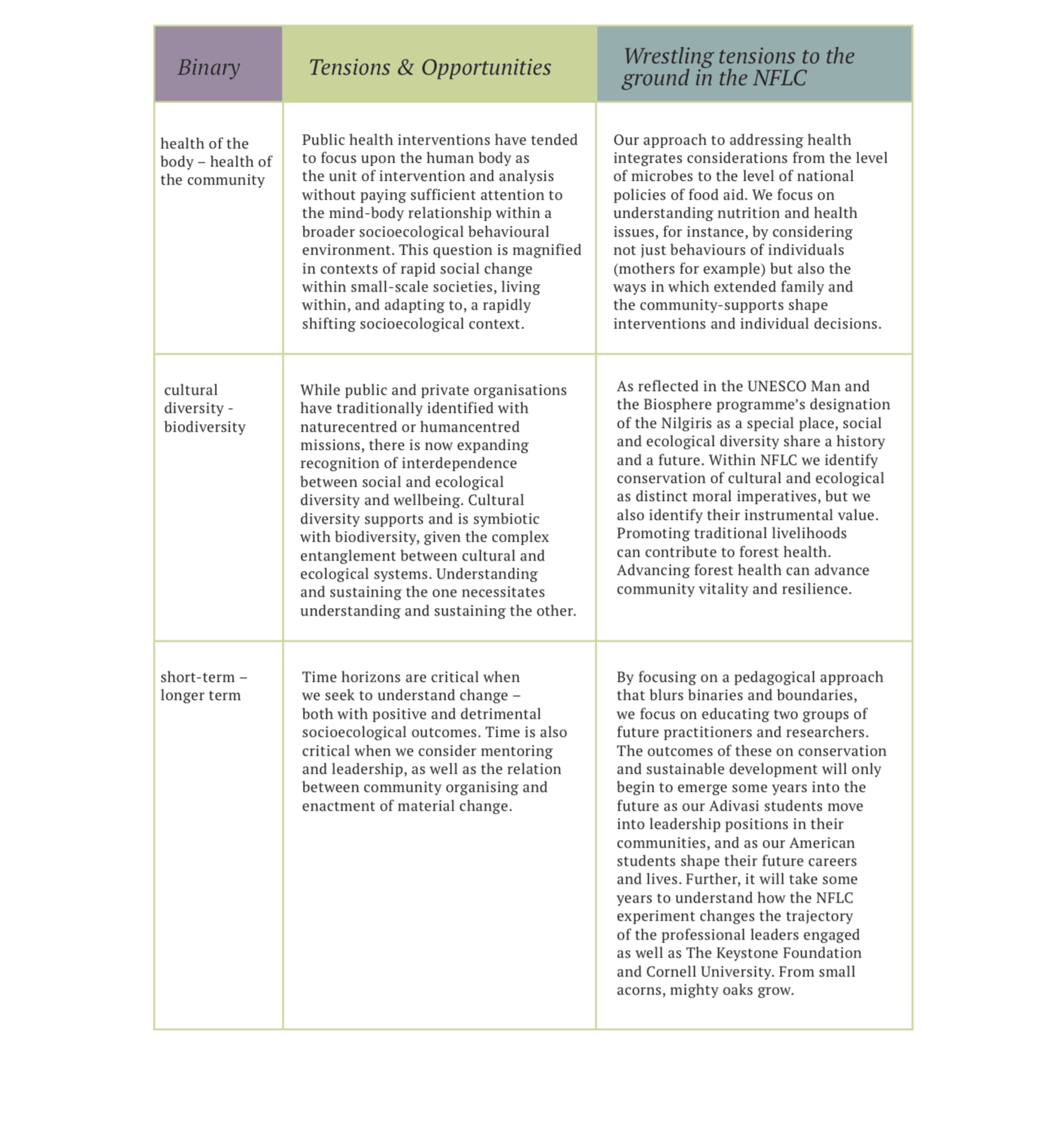

These three integrated approaches to conservation highlight a range of binaries – considerations or categories that are traditionally set in an oppositional relationship. The ecology-economy binary receives the most attention, but we must also recognise other categories and boundaries (we list additional binaries that we identify as consequential in Infographic 1). Addressing these contrasting ideals and the relationships between them in specific places and contexts presents opportunities to relax tensions and to develop new ideas and practices. Through our work in the NFLC, we have developed curricula, community-engaged research projects, and ways of working that blur traditional boundaries and advance an encompassing integrated approach to the conservation of people and nature. In advancing a next-generation approach to environmental conservation and sustainable development, we identify an opportunity to both broaden the conversation and attract new actors, interests, legitimacy, and energy.

Radical collaboration: towards an ambitious integration for sustainability

The focus of the NFLC is sustainable development through radical collaborations. We pursue integration by focusing on blending and blurring categories identified in the figure above rather than by focusing on any one model that seeks integration across the economy, ecology, and health. The programme – which is bilingual – is premised on partnerships among Cornell University-based researchers-educators and undergraduate students from across disciplines, Keystone Foundation staff rooted in practice, and Adivasi students from the communities Keystone works within the Nilgiris. Our ability to bring Adivasi students into these partnerships rests largely on collaboration with the Keystone Foundation and their relationships with 12 tribal groups, who make their livelihoods through a combination of strategies that include subsistence agriculture, growing small quantities of commercial crops like tea or coffee, wage labour in plantations and other regional industries, and gathering non-timber forest produce such as honey. The NFLC is intentionally structured around the expertise and experience of varied groups to integrate knowledge pluralism, experience, interdisciplinarity, and diversity into every learning interaction. By bringing university students from the global North to Kotagiri to live, study and conduct field research with tribal peers from the Nilgiris, we invite and structure cultural collisions that present opportunities for fundamental reflections on what constitutes valid knowledge, the fluidity of cultural norms, and the range of social and ecological interactions that structure opportunities and constraints to conservation.

The multidimensional conception of conservation represented by the NFLC is illustrated by the set of seven research briefs published by NFLC students in the online supplement to this issue of Current Conservation. The articles address forest governance, human-wildlife conflict, sanitation, water resource management, nutrition, health, and healthcare in the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve. In terms of research, the attention to ecological and socioeconomic concerns points to the integrated approach to analysis and development we seek to advance within the NFLC. In terms of pedagogy, bringing undergraduate research to publication – both Cornell and Keystone students’ – in a manner tightly linked to an educational programme is, itself, an example of crossing boundaries.

Are we succeeding in our efforts? Going by measures tracking learning outcomes for students in the short-term, yes. We track changes in student behaviour and attitudes as well as proficiency, skill, and knowledge acquisition at the end of their 15-week programme in Kotagiri. The results, and the numbers of our Cornell students pursuing Honor’s Thesis when they return to Ithaca, make us cautiously optimistic that our curricular innovations are producing positive results for students interested in sustainable development. Our ability to recruit Cornell students to join the programme on a consistent basis remains an open question. The NFLC has a reputation on campus for being a rewarding but intense and demanding experience, and many students who seek to study abroad may be attracted to looser, less ambitious programmes. The Tribal Advisory Council convened by Keystone continues to support the programme enthusiastically, and the NGO partners at NFLC note two significant organisational impacts: they have moved into new programme areas in community health and human-wildlife interactions to further their goals of eco-development. They are also able to partner with and absorb talented Adivasi students into their work, even as they note being stretched in ways they had not anticipated. Progress on the collaborative research projects between Cornell faculty and Keystone staff, however, remains uneven due to a number of reasons including lack of faculty and staff time, difficulties in raising money to support collaborative research embedded in communities, and the challenges of combining the norms of scientific research with the practical demands of delivering support to communities. Our successes at creating an integrative model of learning and action that blurs boundaries allow us to remain optimistic, even as we continue to experiment in efforts to combine our strengths to develop pragmatic responses to the challenges of ecological conservation and sustainable development in the Nilgiris.

We acknowledge the valuable contributions of reviewers and editors supporting Current Conservation, and we thank Anna Callahan and Brian Hutchinson for editorial assistance at Cornell University. We want to recognise the contributions of Paige Wagar of Cornell University and Vijayan, an NFLC student who lives in the Sathyamangalam region.

https://www.currentconservation.org/categories/slow-conservation-themes/