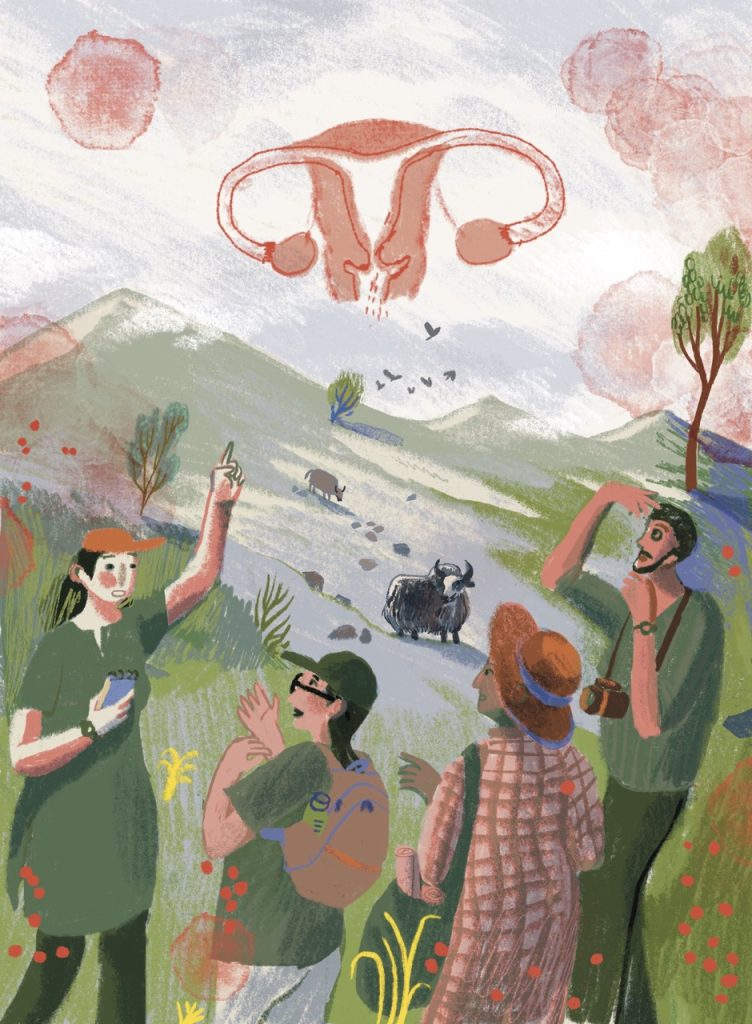

Identity and access are multifaceted and tied to questions of equity and justice. This piece is set in the context of wildlife conservation and (eco)tourism at Corbett Tiger Reserve in Uttarakhand, India. Nature guides and labour for hotels are two common forms of (eco)tourism work for villagers. I offer two vignettes or snapshots from the field that capture the lived experiences of such villagers. They speak of the impacts of (eco)tourism, and more specifically the different people’s engagement with (eco)tourism in the context of their everyday lives that confront rural realities, identities, and conservation. Albeit snapshots, these instances are playing out in the same context and offer insights on how differential engagement or villagers’ relationship with (eco)tourism is, particularly when their identities differ.

The elephant in the village and forest

It’s dark inside the room and I hear my name being called out through the window. I open my eyes, disoriented but rapidly gaining awareness that there must be an important reason for my being woken up at what feels like the middle of the night. I’m about to open the door when I hear “elephant, elephant!”

I run out of the room and follow family members of the house where I am living in Kumer* village. We walk carefully and swiftly through the early morning fog, on a narrow path that connects their home to other homes and farms in the village. We all feel a combination of excitement and fear at the likelihood of spotting an elephant close by. I am told that we need to make sure that the haathi (elephant) doesn’t go further inside the village—it could damage more crops, property, or life. The key is to make loud sounds in the hope that the elephant can be rerouted to the forest. Not having seen any signs of the elephant in the village, we assume it has returned to the forest.

We return home and survey the damage to the paddy crop. This is a seasonal phenomenon: elephants love the paddy flowers, and annually raid the paddy fields. It is a constant challenge for the villagers to protect their crops from elephants, and other animals including nilgai, and sometimes boars.

This village, where I was living, lies close to the Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR) located in the northern state of Uttarakhand. In 1973, Corbett Tiger Reserve became one of the first areas designated to be set aside for tiger protection. Since then, villages around the protected area have been significantly influenced and impacted by the tiger reserve. One of the major influencing factors has been (eco) tourism. Ecotourism is promoted as a means for educating tourists about nature and wildlife, providing employment to local people, and contributing to the protection of wildlife or forests. Ecotourism is meant to be low impact and create minimal disturbance to the landscape and people. However, CTR’s proximity to the National Capital Region—which encompasses Delhi and several districts surrounding it from the states of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan—makes it more accessible, which has also contributed to the growth of all kinds of other tourism. One of the most common forms of ecotourism at CTR is safaris.

So how is the elephant incident relevant here? For most tourists visiting this landscape, at least one jungle safari is part of their itinerary. Jeep safaris are led by a guide and a driver both of whom are generally from the nearby villages. Spotting elephants and of course tigers is a sign of a successful safari. Tourists in safari jeeps passing one another ask whether they have spotted a tiger, or any other majestic wildlife.

During peak tourist season (winter months) there can be over 200 safaris per day. And the hope—for the jeep drivers, guides, and tourists—is to spot a tiger, or at least an elephant. The guides or drivers often have their own crops damaged by elephants, yet the value of spotting an elephant or other wildlife during the safari ties into the material benefits they gain. But for the villagers outside the CTR boundaries, spotting a tiger or elephant in their villages has no benefits—it only brings crop loss, property damage or loss of life.

Women’s work and precarity

“I helped build that hotel. I would walk up two and three floors with a load on my head. Today, no one will speak up to say who built that hotel.” In conversations with women whose families are unable to own land due to disadvantaged class and caste, (eco)tourism work has a different level of precarity. Another woman who works as farm labour adds, “There is more land sold and less farm work for us. There will be more and more hotels, and villagers will go away. The villagers have their land, our daily wage often comes from farming on their lands. So, if they have sold their lands, where will we get work from?”

These are only two of the hundreds of stories of women who work as labour in the village, households, and (eco)tourism, and whose work remains invisible. As some villagers have become entrepreneurs and shifted away or reduced farming, such women have reduced access to traditional livelihood work, or they become part of the (eco)tourism economy. The face of the tourism enterprise, households and land is men, yet a significant amount of labour work is put in by women. Women who come from landowning families have been able to engage with the (eco)tourism market in the form of homestay work or administrative work in hotels. For some, (eco)tourism-based work provides marginal mobility with continued precarity. This is true of all tourism-based work.

Women continue to walk a tightrope as they try to tap into forms of agency, while navigating the realities of the patriarchy. Their involvement with the market offers an avenue to understand how culture, market values, and agency coexist and contradict each other. It is in such spaces of women’s work or guides’ decision making towards their land use, that one could locate where and how agency can be expressed and amplified.

Negotiating (eco)tourism

The Corbett landscape is notorious for the contentious use of land for tourism and infrastructure influenced by powerful actors. All these factors have contributed to changes in livelihoods and change in the physical landscape. The rural landscape around CTR has several hotels, guest houses, resorts, restaurants, shops, and tea stalls. While farming and livestock keeping have been common livelihood practices here, (eco)tourism has become a common avenue for diversifying household incomes or shifting away from traditional livelihoods.

Simultaneously, there is a common understanding of the symbolic value of land, beyond the material. Socio-economically well-off villagers have been able to set up their own enterprises and engage with tourism as owners or managers rather than labour. Despite the seasonal nature of tourism, engaging with (eco)tourism is a matter of surviving market dominance, and one way to continue to live in their homes rather than out-migrate.

This was the context for my doctoral research: examining how local people are negotiating and responding to Corbett Tiger Reserve (eco)tourism. Using a critical feminist political ecology lens, it was important to understand how and why people are engaging with (eco)tourism. This lens helped locate the complexities of peoples’ responses, which were shaped by their socio-economic identity, and the extent to which they can navigate a changing rural landscape.

The landscape is thus riddled with contradictions and shifting positionalities as villagers, over the years, have learnt to negotiate and engage with the (eco)tourism market. The benefits or losses from tourism are variable, and it is precisely this complexity that calls for more attention. The focus on identity in my research was a result of the variations in access and abilities to engage with the market or continue farming. Identity is also tied to agency, and for conservation governance, it is crucial to understand who is affected by conservation policies, why and how, if we are to work towards equity and justice.

*A pseudonym is used for the village name

Further Reading

Mazoomdar, J. (2012, May 4). Corbett. Now, On sale. Mazoomdar. https://mazoomdaar.blogspot.com/search?q=Corbett

Mishra, I. (2022, October 21). Central committee to probe ‘illegal’ felling of trees in Corbett National Park: NGT. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/central-committee-to-probe-illegal-felling-of-trees-in-corbett-national-park-ngt/article66040340.ece

Pandya, R. 2022a Intersecting identities and altered relations: Locating the material and symbolic factors shaping local engagement with ecotourism at India’s Corbett Tiger Reserve. PhD thesis, Wageningen University. ISBN: 978-94-6447-406-0

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18174/577012

Pandya, R., Dev, H.S., Rai, N.D. and R. Fletcher (2022) Rendering land touristifiable: (eco)tourism and land use change. Tourism geographies 25(4): 1068–1084.

Pandya, R. 2022. Micro-politics and the prospects for convivial conservation: Insights from the Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Conservation and Society (20)2: 146–155.

Pandya, R. 2022b. An intersectional approach to neoliberal environmentality: Women’s engagement with ecotourism at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Environment and planning E: Nature and space 6(1): 355–372.