The forest meant different things to me as a visitor and as a resident, in a jeep or on foot. I spent my last summer working at Earth Focus Kanha, an environmental non-profit that works on education, conservation, and livelihoods development in fourteen villages around Kanha National Park. The organization works with Baiga and Gond forest dwellers who live in these villages, and who were evicted from the park to create a tiger reserve. I had visited the park a few months earlier, with my mother, on a short safari trip. On the third day of our trip, we had the rare sighting of a tiger on foot during a guided evening walk on the Bamhni Nature Trail. This was the same tiger we had seen on our safari earlier that morning.

5:30 p.m., Bamhni Nature Trail. The river bleeds through the landscape. It’s early May, the water is low, and there is silence on the rocks. As light spills onto the canopies, a gaur (Indian bison) becomes visible on a distant boulder. The horned bovine is three-thousand pounds of muscle and a hump, and he is staring at us. The evening shifts, leaving us in shadow.

Karan, my mother, and I sit under a ghost tree by the riverbank. Karan is a naturalist who leads forest walks along the Bamhni Nature Trail in the buffer zone of Kanha National Park. Nestled in the monsoon forests of Central India, the park is home to tigers, elephants, leopards, bison, deer, and a host of wild bird, insect, and plant species. Ma and I are here for four days on a long-anticipated mother-daughter bonding trip. We’re staying at a tented camp near the park. We went for a safari this morning.

Despite the staggering diversity of creatures Kanha is home to, like the twelve-horned barasingha or swamp deer, the red-billed green munia bird, and the rust-colored dhole or Indian wild dog, tigers remain its main attraction. Specifically, the Royal Bengal tiger, a striking and aptly named subspecies of tiger that is found in India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, and Nepal. Madhya Pradesh, the Central Indian state that Kanha is located in, is home to 526 tigers spread across six reserves: Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Pench, Satpura, Panna, and Sanjay Dubri.

Tigers fall under the category of charismatic megafauna – “large, popular endangered animals” that captivate public attention. Because of the hype that surrounds them, tracking tigers becomes the unwritten goal of most safaris. Field guides and naturalists accompanying tourists on safari jeeps exchange notes and latest sightings as they cross one other. They listen for alarm calls and track pugmarks in the mud. And at the end of the day, when tourists return to their lodges to mingle over dinner, they ask one another, “So, did you see a tiger?”

5:00 a.m., Kanha National Park. We leave the camp early. Dawn is breaking, and I can hear the early calls of the copper-winged coucal. The air is brisk. I huddle in Ma’s shawl at the back of the jeep as the woods blur into green on either side. We arrive at the park gate. The officials check our IDs and entry slips. Then we are inside.

By 8 a.m. it is torrid. The sun is scorching white, so I wrap the shawl around my head for shade. So far, we’ve spotted elephants, langurs, wild boars, jackals, barasingha, barn swallows, and a crested serpent eagle. The safari has brought us into the heart of the forest. We are on a trail that runs parallel to the Banjar River, straitened by unruly grasses and invasive wild mint.

Suddenly, the field guide asks the driver to brake. He points to the left, holding a finger to his lips so we know to remain silent.

There is a rustle in the undergrowth, followed by a low growl. A tigress strides onto the trail. Her matted fur is emblazoned with billowing, black stripes in an unrepeatable pattern. The guide whispers to us that her name is Chhoti Mada.

Two elephants, bestrode by mahouts, emerge behind her from the copse. Chhoti Mada glares at the jeeps before returning to the thicket.

When she is gone, the guide surmises that the mahouts had pushed her onto the trail. There are “VIPs” in the jeeps ahead who haven’t had a sighting yet, hence the spectacle. Goaded by the mahouts, Chhoti Mada was probably forced to exit the bush and make an appearance.

Chhoti Mada is also a mother. She left her cub inside, the guide tells us, so he remained hidden while she was gone.

Tigresses give birth to litters of one to seven cubs, which they raise with little to no help from the male. Cubs cannot hunt until they are 18 months old, and their mothers guard and nurture them until they are ready to disperse and claim their own territories after two to three years. Approximately half of all wild tiger cubs do not survive beyond two years, so tigresses are fiercely protective of their cubs. They will risk being fatally injured to keep them safe.

6:10 p.m., Bamhni Nature Trail.

“We should leave,” Karan says. He is perched on a boulder and looks uneasy. Ma agrees. “It’s getting late, Yaash,” she says. “Let’s go.”

“Can we please stay for ten more minutes?” I ask. “It’s so peaceful here.”

Karan shrugs. They relent.

In end-of-the-century London, Samuel Butler cocmplained that “there is a photographer in every bush, going about like a roaring lion seeking whom he may devour.” The photographer is now charging real beasts, beleaguered and too rare to kill. Guns have metamorphosed into cameras in this earnest comedy, the ecology safari, because nature has ceased to be what it always had been – what people needed protection from. Now nature – tamed, endangered, mortal – needs to be protected from people. When we are afraid, we shoot. But when we are nostalgic, we take pictures.

Susan Sontag, On Photography

7:00 p.m., Bamhni Nature Trail.

Halfway home on the walk with Ma and Karan, alarm calls sweep the forest. We are halfway home. We would’ve been three-fourths of the way home had we left ten minutes earlier. This is Chhoti Mada’s territory.

In the falling dark, I reach for Ma’s hand. Karan instructs us to shelter under a sprawling saj tree. My fingers grow numb.

Ma thrusts me behind her. She assumes a defensive posture. Minutes pass.

It’s one thing to spot a tiger from the safety of a safari jeep, and entirely another to hear a swish in the grass. To catch a flash of orange.

While working at Earth Focus Kanha in June and July of last year, I lived in Manji Tola, a village located near the Mukki Gate of Kanha National Park. I lived in the team residence with other employees, most of whom were native to Kanha and identified as either Baiga or Gond.

The residence was constructed from shipping containers and painted a deep green to blend in with the surrounding sal forest. I wasn’t allowed to step out alone after dark and would be chastised for going on long walks in the forest. My colleague Bhola told me that a few months ago, he’d seen a tiger – Pattewallah (“the one with the collar”) – roaming the periphery of the campus. This was his territory. I’d seen and even photographed Pattewallah, a handsome and formidable tiger, on one of the three safaris I’d been on with Ma the previous month. But here, without the safety of a jeep, I was prey.

From stories other colleagues told me, and from the fear I felt when my torch ran out of batteries or a black scorpion scuttled into my room, I began to grasp the fraught relationship forest dwelling communities have with the wild. The jungle is veined with serpentine roads and unpaved trails, which we, like most people living in Kanha, traveled on foot or via motorcycle. A motorcycle is a speeding hunk of metal exposed on all sides, supporting up to four people (who, in Kanha, likely aren’t wearing helmets). It’s little protection during a chance tiger ambush.

Professor Ruth DeFries, an environmental geographer who is researching approaches to conservation in the Central Indian Highlands, tells me: “We think wildlife should just be conserved, but the reality is different for those who live here. Crops are eaten by chital , people are afraid to go into the forest because of tigers and leopards… you realize that it’s not so rosy, that living with wildlife is really quite difficult.” In her research, philanthropy, and advocacy, DeFries argues for “people-oriented approaches to conservation” in Central India.

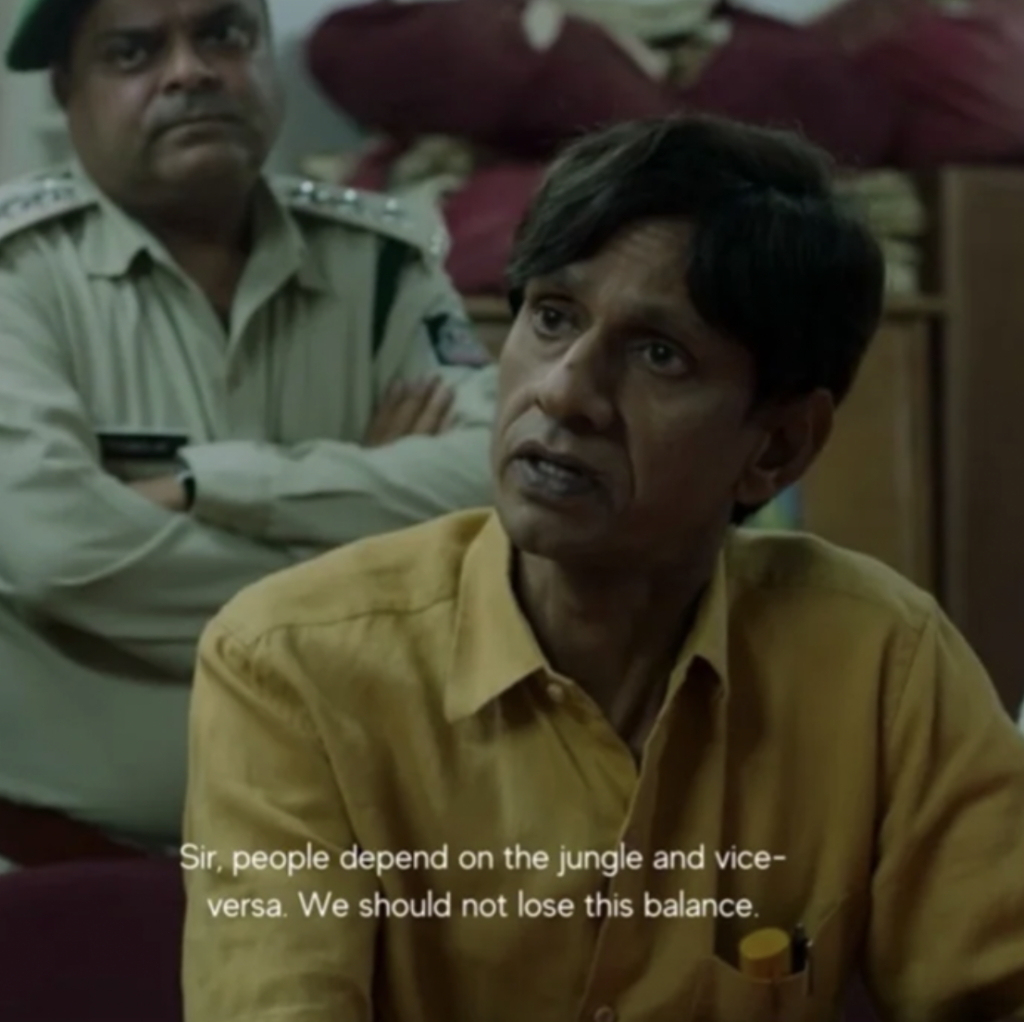

Bollywood is also beginning to grasp these tensions, and the 2021 film Sherni (“tigress”), starring actress Vidya Balan as a divisional forest officer, turns the spotlight on issues of human-wildlife conflict, indigenous forest rights, poaching, and the deep sexism and petty bureaucracy of the Indian Forest Department. The film also discusses approaches to conservation. The screengrabs below are from the film juxtapose two perspectives on conservation: the image on the left explains a top-down “fortress conservation” approach that prioritizes wildlife protection, while the one on the right describes a rights-based approach (like the kind DeFries advocates) that involves local communities and honors their rights.

9:00 p.m., Camp. We’re back in our tent. Ma showers and changes into her nightclothes. She’s asleep with minutes. Meanwhile, I remove the memory chip from my Nikon Z50 and insert it into my laptop. While clicking through the day, I come upon photographs of Chhoti Mada and the mahouts. My stomach grows cold. I crawl into Ma’s bed and switch off the lamp.

Further Reading

- Elwin, V. Leaves From the Jungle: Life in a Gond Village. 2d ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Mathur, N. Crooked Cats: Beastly Encounters in the Anthropocene. The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

- Guha, R. Savaging the Civilized: Verrier Elwin, His Tribals, and India. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999.