In India, dugongs inhabit waters around the Gulf of Kutch, Gulf of Mannar, Palk Bay and the Andaman & Nicobar archipelago. Our research has gathered new clues about a crucial part of the dugong’s life that occupies much of their time; their feeding habits in seagrass meadows. The search for answers started seven years ago when we sighted two dugongs while snorkelling around an island in Ritchie’s archipelago. We observed these two individuals closely for months and found them feeding in the same seagrass meadows throughout the year. They fed specifically on two species of seagrasses that were relatively small-sized and low in density. This led us to wonder how these animals managed to feed constantly in an area without depleting their resources completely.

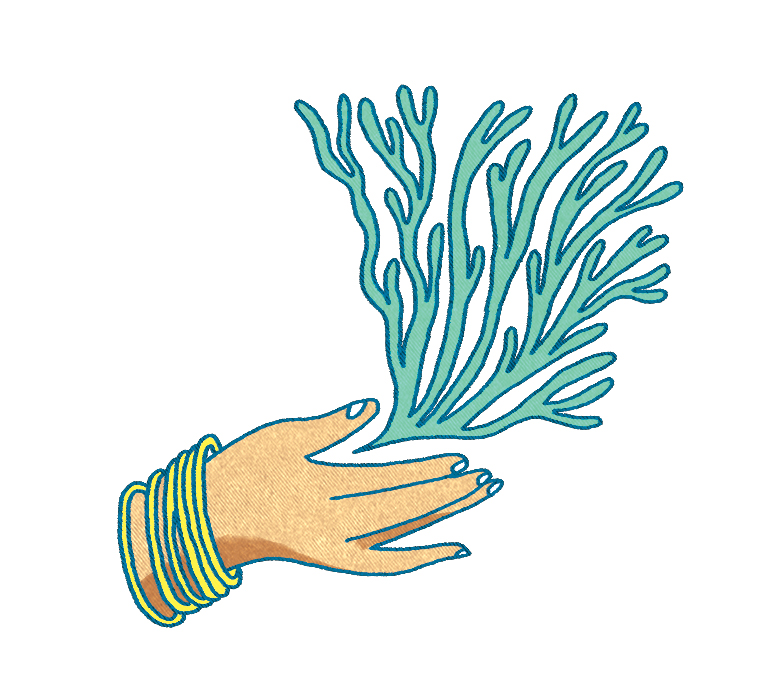

Dugongs are known to feed on high-nutrition and low-fibre species of seagrasses, typically pioneer species. Where animals exist in large numbers, such as in Australian waters, they are known to graze down meadows, reducing biomass by almost 80 to 90%. By uprooting entire shoots and then abandoning the meadow to allow them to recover for a period before they return, the dugongs tend the meadows and are therefore considered as ‘seagrass gardeners’. The time interval between two visits to a patch is long enough to ensure the recovery of the same species but short enough to prevent the next level of succession which would comprise low-nutrition, high-fibre species that are not optimal for the dugongs’ diet. In the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, populations of dugongs have dwindled considerably in the last five decades and we were observing persistence in habitat use, in contrast to abandoning of overgrazed sites. Hence, we tried to understand this difference in a more systematic manner.

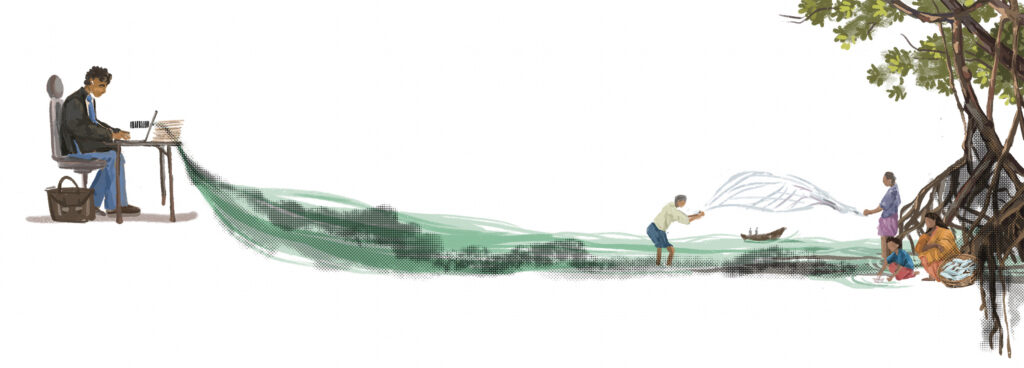

We had observed eight seagrass meadows (of the 44 surveyed) that were used by dugongs over a period of four years. We monitored these meadows and found signs of the animals feeding throughout the year at these sites. We also observed that each of these meadows was used either by individuals or pairs of dugongs. To increase our sightings of animals in and around seagrass meadows, we also set up a network of informants comprising fishermen, tourist boat operators and dive operators, who used the waters frequently.

From this network’s and our personal observations, we estimated a total of fifteen individuals over a period of seven years around Reef, Havelock, Inglis, Neil, Sir Hugh, South Andaman, Nancowry, Trinket and Teressa Islands.

In order to better understand why animals repeatedly used certain seagrass meadows, we measured the magnitude of dugong herbivory in the eight meadows where feeding signs were observed. All these meadows had distinct characteristics—they were all relatively large, unfragmented, continuous in seagrass cover and dominated by the pioneer species Halophila ovalis, Halodule uninervis and Halodule pinifolia. About 15% of the total production of seagrass was consumed by dugongs across these meadows. The recovery of meadows after a feeding event was also quick, taking little longer than a week to return to original shoot densities. Through experimental manipulations, we tried to understand the short term impacts of dugong herbivory on seagrasses. We created cages of fixed sizes in replicates at several meadows where dugongs fed. These cages were such that they allowed seagrasses to grow without altering the natural conditions but prevented them from being consumed by dugongs. We found that when herbivory was excluded for six months and longer, the shoot densities were almost 50% higher within the exclosures than in the surrounding meadow that was actively foraged upon.

The data obtained from herbivory exclosures when combined with direct observations of animal presence revealed that dugong feeding in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago is not limited by the availability of suitable resource habitat. The proportion of primary production consumed by dugongs does lead to a reduction in seagrass shoot densities but not to levels that trigger meadow abandonment. The ability of seagrasses to cope with such levels of herbivory perhaps explains the long-term site fidelity shown by individual dugongs in these seagrass meadows.

Our long term research from the islands has several important implications. Firstly, the low number of dugong sightings implies that conservation of the remnant populations is of utmost significance. Secondly, the dugongs in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago exhibit feeding behaviour that is probably typical of small populations and was not documented earlier. Taking advantage of the site fidelity of the species, the management can focus on monitoring and protecting these sites and ensuring no further decline in the population. However, the short term movement of dugongs can be governed by other factors too such as male and female mating strategies, escape from predation, calf protection, anthropogenic noise, and oceanography, among others. Therefore, in the future, these factors should be studied and considered while developing long term management plans for species conservation. At present, the dugong populations around the islands are dwindling and any further decline could lead to a level below which species recovery may be unlikely. Therefore, it is critical to safeguard the sites where dugongs occur to allow these wonderful gardeners of the sea to persist.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr Teresa Alcoverro, Dr Núria Marbà and Dr Rohan Arthur for helping The proportion of primary production consumed by dugongs does lead to a reduction in seagrass shoot densities but not to levels that trigger meadow abandonment. The ability of seagrasses to cope with such levels of herbivory perhaps explains the long-term site fidelity shown by individual dugongs in these seagrass meadows. design this study, the Department of Environment and Forests, Port Blair for research permits and all at the Andaman and Nicobar Islands’ Environmental Team (ANET) for their help and support.

Photographs: Vardhan Patankar