I live on a small island called Havelock, in the Andamans, and I work in a SCUBA diving school for a living. Using my background in marine biology, I conduct research on coral reefs around Havelock and take people out diving to introduce them to some of the many living jewels of the sea.

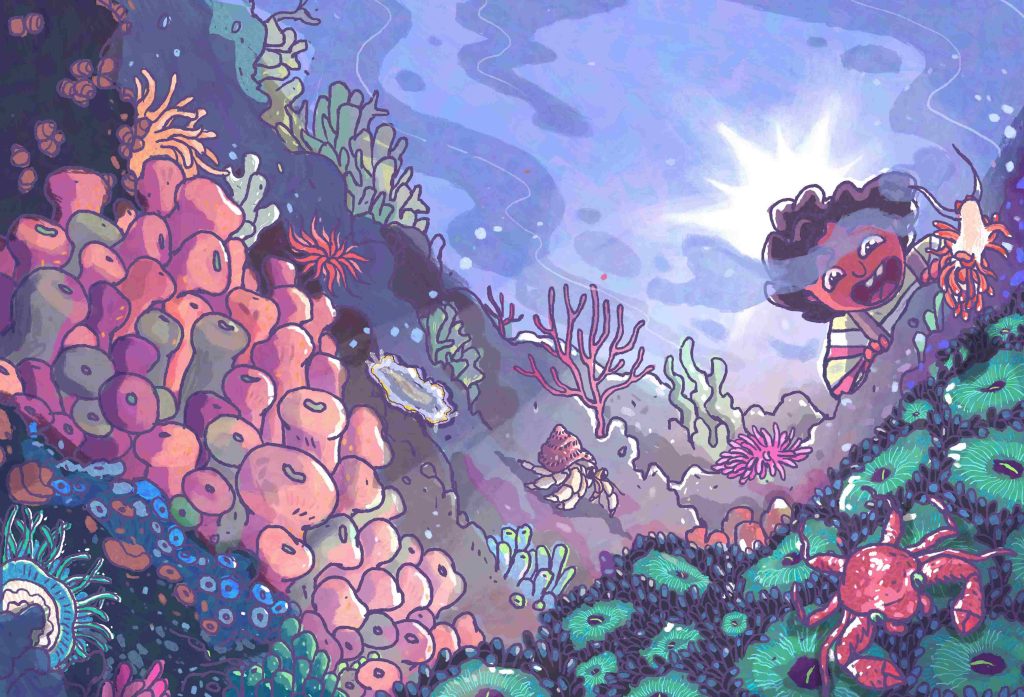

Corals are colourful animals, related to jellyfish, that slowly but carefully build the limestone structures that form reefs, on which a diversity of other marine life thrives.

A majority of the corals around the Andaman Islands died in one dramatic episode in 2010, in a phenomenon called “mass bleaching”. This also happened to other corals in the Indian and Pacific oceans. We know that corals were bleached and killed at that time due to the warming of the oceans and increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. What we do not fully know yet is: How are coral reefs recovering? And why are some reefs recovering faster and others slower?

Through my research around Havelock, I am trying to answer these questions. I survey damaged coral reefs to study how much new coral is growing back, and what species these are. I also try to find out whether there are any factors that might prevent coral from recovering smoothly.

Preparing for a day of fieldwork diving is very similar to getting ready for a day in the forest, except that my dive buddy and I load up a boat instead of a jeep! We wear neoprene wetsuits beforehand but set up our SCUBA gear and research equipment on the boat. We never forget to carry food, water, and emergency medical kits.

Using a handheld GPS, we navigate to a mooring line above our dive site, Minerva. Once anchored, my dive buddy and I help each other carefully put on our SCUBA gear. Before jumping into the water, we split the load of all the research tools that need to be taken so that our descent to the bottom is smooth. We want to avoid having a camera floating up this way or a measuring tape sinking down that way!

Once at the bottom there is no time to waste because our full tank of air will allow us a dive time of one hour at most. My buddy gets to work, reeling out the 30-meter long tape over the reef that we are surveying. I place a 1-meter square frame, called a quadrat, over the coral. Then hover above it to photograph the coral—and everything else—that lies within the outlines of the square frame. With the tape to guide me, I collect this photographic data every ten meters along with the measuring tape. We survey several such transects to make sure we have sufficiently covered the dive site.

In the last ten minutes of the dive, we swim over and check on the data loggers we had previously placed at Minerva. These loggers have sensors that automatically measure temperature and light intensity underwater for months on end, and the data loggers store all that information. We regularly visit them, with a toothbrush in hand, to scrub off sand and algae that settle on the sensors and interfere with their working properly.

Within an hour of finishing our dive, we are back on land, rinsing off the salt from our SCUBA and research tools with fresh water. After a hot lunch and an afternoon nap to get over post-dive drowsiness, I am ready to start processing my quadrat photographs of coral. This part of fieldwork is almost as exciting as the actual diving itself (if it did not involve hours of computer work!). I still thoroughly enjoy analysing my quadrat photos—identifying different corals and measuring their sizes. The next step would be to look at whether temperature and light intensity in Minerva and other dive sites make a difference in how these animals are recovering. This is when I get to really start answering my research questions, by documenting coral recovery. Someday this information could enable us to help reefs in crisis!