The Elephant Task Force proposes to eventually ‘phase out’ the use of elephants in commercial captivity through a massive tightening of the law. Not surprisingly, owners are far from happy, and the State Forest Departments in a quandary.

The captive Asian elephant is something of a legal oxymoron. Few other wild animals, Schedule I species at that, are in such extensive commercial use. Some 3,500 elephants in India, mostly captured from the wild, have been trained by human ingenuity to ferry tourists, ‘bless’ the devout, parade in festivals and log timber in forest camps.

Not least because of the oddity of their position, this large section of elephants has slipped through the cracks in the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA). Whether it is ownership, trade, upkeep, or its use, the captive elephant is exempted from almost every provision the WLPA extends to wildlife.

Unlike all other forms of wildlife, elephants can be ‘owned’ privately while the WLPA specifies that all wildlife is the property of the Government. The only specific reference to captive elephants places them in the same category as bullocks, horses, camels, and other domesticated animals, or “vehicles” despite their very specific ecological needs. The fact, however, that these lacunae in the law have for so long remained unaddressed is indicative of an important cultural reality in India (and several Asian countries): the elephant has, over the centuries, become an integral part of well-entrenched traditional or religious practices and more importantly, a source of livelihood for thousands of mahouts and kavadis.

There are no precise figures for the number of captive elephants India has. But of the estimated 3,500 elephants, half are in northeast India, and another 900 in southern India. Northern and eastern India are thought to have between 200 and 300 each, while western India has some 80. Indeed, the dilemma that these creatures pose and the sheer numbers they represent-they account for approximately 10 percent of all elephants in India-make them impossible to ignore. It was only inevitable, therefore, that the first major report on the status and future of elephants in India, ‘Gajah,’ written by scientists, academics, and activists comprising the 12-member Elephant Task Force, should dedicate an entire chapter to the captive elephant. The report, submitted in August 2010 to the Ministry of Environment and Forests, recommended among other things that the elephant be declared a “heritage animal.”

The report bases itself on the premise-one held by field biologists, scientists and scholars of elephant behaviour that elephants have unusual social complexity, significant cognitive abilities, that they are “self-aware individuals, possessing distinct histories, personalities and interests, and that they are capable of physical and mental suffering.”

Beginning here, the Task Force recommends a string of modifications to the WLPA in an attempt to bring within its umbrella the curious case of the captive elephant. The eventual goal, it adds, must be “the complete phasing out of elephants from commercial captivity.” This somewhat controversial proposition is appended with an acknowledgment, however, that “the elephant is integral to cultures, religions and livelihoods in many parts of India have a long tradition of elephant keeping and handling.” The chapter then sets itself the more immediate target of “improving their condition in captivity” by clamping down on their capture, taming, sale, transfer, and ownership.

The elephants used for logging operations in government forest camps are comparatively in better shape, owing perhaps to their proximity to their natural habitat. But the biggest chunk of captive elephants are in commercial captivity predominantly in temples, circuses, tour operations or used to beg for alms, and the condition of many of them is debatable. And studies have shown that the worst off are temple elephants, an estimated 1,200 of them-being farthest removed from their natural ecological needs. Tethered for days on end, their rearing is often unscientific and their nutritional status poor. This group of elephants is also prone to a variety of ailments from anaemia to foot-sores and tuberculosis. Every now and again there are unsettling reports of temple elephants going ‘beserk,’ breaking loose and even killing people while on a rampage.

The use of elephants in circuses has also caught the attention of the Task Force that has called for its ban. “This category of privately owned elephants should follow the precedent of phasing out as per the 1991 ban of the five categories of wild animals (lion, tiger, leopard, bears and monkeys) in circuses.” It also recommends the prohibition of elephants in weddings, unregulated tourism, public functions, begging, and other forms of entertainment.

If the Task Force has its way, no one but the government would ‘own’ an elephant. The Task Force recommends that the word ‘ownership’ be replaced with ‘guardianship’. Individual State Forest Departments will take over ownership and also establish ‘Captive Elephant Lifetime Care Centres’ to take care of animals abandoned, confiscated, or captured.

Guardians, whether individuals or agencies, should also be given a ‘guardianship certificate’ or ‘passports’ with photographs and complete details of the elephants, which will be micro- chipped “in order to ensure that the elephants enter into a central and state system of monitoring.” If implemented, these and other legal interventions such as the ban on new acquisitions of wild-caught elephants for commercial use, their sale, and ownership could indeed serve to realize the eventual goal of the Task Force, i.e, the phasing out of captive elephants in commercial us.

The proposal has, not surprisingly, met with opposition from owners and temple authorities. October 4, the ‘National Elephant Day’ was observed as a ‘black day’ in Thrissur: the Guruvayur temple here has one of the largest collection of elephants at around 70. The Kerala State Elephant Owners’ Federation and the Kerala State Pooram-Perunnal Festival Coordination Committee said the Task Force had failed to consider “the state’s cultural and religious traditions” and that the Thrissur Pooram that draws in thousands of tourists, will be unimaginable without the caparisoned procession.

And if owners were allowed only a guardianship of their elephants, they argued, the government must take up the responsibility of maintaining elephants. An elephant costs an annual Rs. 3 lakh to maintain and Rs 1.5 lakh to cremate, owners pointed out. The Kerala Forest Department chose not to “antagonise large communities” by enforcing legislation such as this. The department endorsed a “transparent way” of selling, gifting and donating elephants. It also admitted that it cannot take up the ownership of the 800 elephants in the State, the department added.

In another incident a couple of months earlier, in August, the Tamil Nadu forest department kicked up dust when it asked temple authorities to stop using elephants to “bless” Hindu pilgrims. The animals had begun to contract tuberculosis (and possibly even transmit it) from the 500 devotees that touched their trunks everyday. Four elephants had recently died of the disease. Hindu groups however said the ban went “against religious sentiment”.

Scientific studies do establish the practice as a health hazard for elephants and humans. According to a study sponsored by the Bangalore-based non-government organization Asian Nature and Conservation Foundation, one in four temple elephants in the southern states has tuberculosis, a ‘zoonotic’ disease that can be transmitted between humans and animals. The prevalence of the disease was as high as 24 per cent among other privately owned elephants (such as circus elephants and those used for collecting alms), while elephants with the forest department fared much better, with a much smaller 11 per cent testing positive for the bacteria.

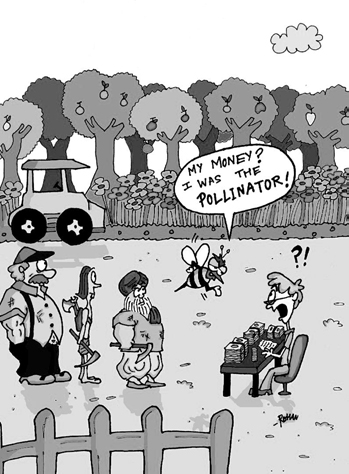

Be this as it may, at least two key problems are bound to arise if the Task Force’s recommendations became a reality. One, what would happen to the 5,000 mahouts and kavadis, the primary caretakers of the captive elephant, who would be inevitably “phased out” too? And two, how will the State Forest Departments, with the meager money, space, and personnel at their disposal take on the ownership of hundreds of these beasts that are now in private custody, or bring under their wing every rogue elephant captured in a human-animal conflict situation?

The report does not suggest a long-term vision for mahouts or alternative livelihood options. It does however acknowledge the mahout as the custodian of traditional knowledge about elephant behavior, as the single most important point of con- tact with the elephant, as someone who is paid a pittance by the elephant owner and as deserving “better employee status” with specific laws to their aid. The Task Force recommends that mahouts in forest camps be recruited at the cadre of forest guards and entitled to hardship allowance, accident insurance, and “bonus for well-kept and healthy elephants.” As for mahouts in private employment, their salaries should be at par with the forest department grades, it adds.

As the privately owned elephants are phased out, an already stretched Forest Department will find its responsibilities bloat. As owners of all the State’s captive elephants and the caretakers of the pachyderms captured or seized, the department is likely to find itself in a logistical conundrum, one that the Task Force offers few solutions to. The Task Force does point to the abysmal lack of wildlife vets and paltry infrastructure that leaves elephants largely devoid of professional care. For instance, Karnataka’s Forest Department, which has some 120 elephants in its camps, has no more than three wildlife vets at its disposal. Many of these elephants are captured “rogue” elephants with pellet wounds that need specialized help, the forest department often laments. The report recommends that “Wildlife Veterinary Wings be set up within the state forest department with full promotional opportunities, incentives, and facilities for the veterinarians with options of permanent absorptions.”

It also recommended a host of other interventions besides additions, deletions, and amendments to the WLPA. These include the setting up of Captive Elephant Welfare Committees to assist the State Forest Departments monitor the condition of captive elephants. To begin with, the Task Force suggests a census of the captive elephant-the first ever exercise of its kind if it is carried out. But with livelihoods and businesses at stake and the current capacity of the State Forest Departments, it is anybody’s guess when or how these beasts will be brought under the ambitious umbrella of measures conceived for them.