It is the 2nd of February 2053.

I am going to tell you how the last of the wild corals were born.

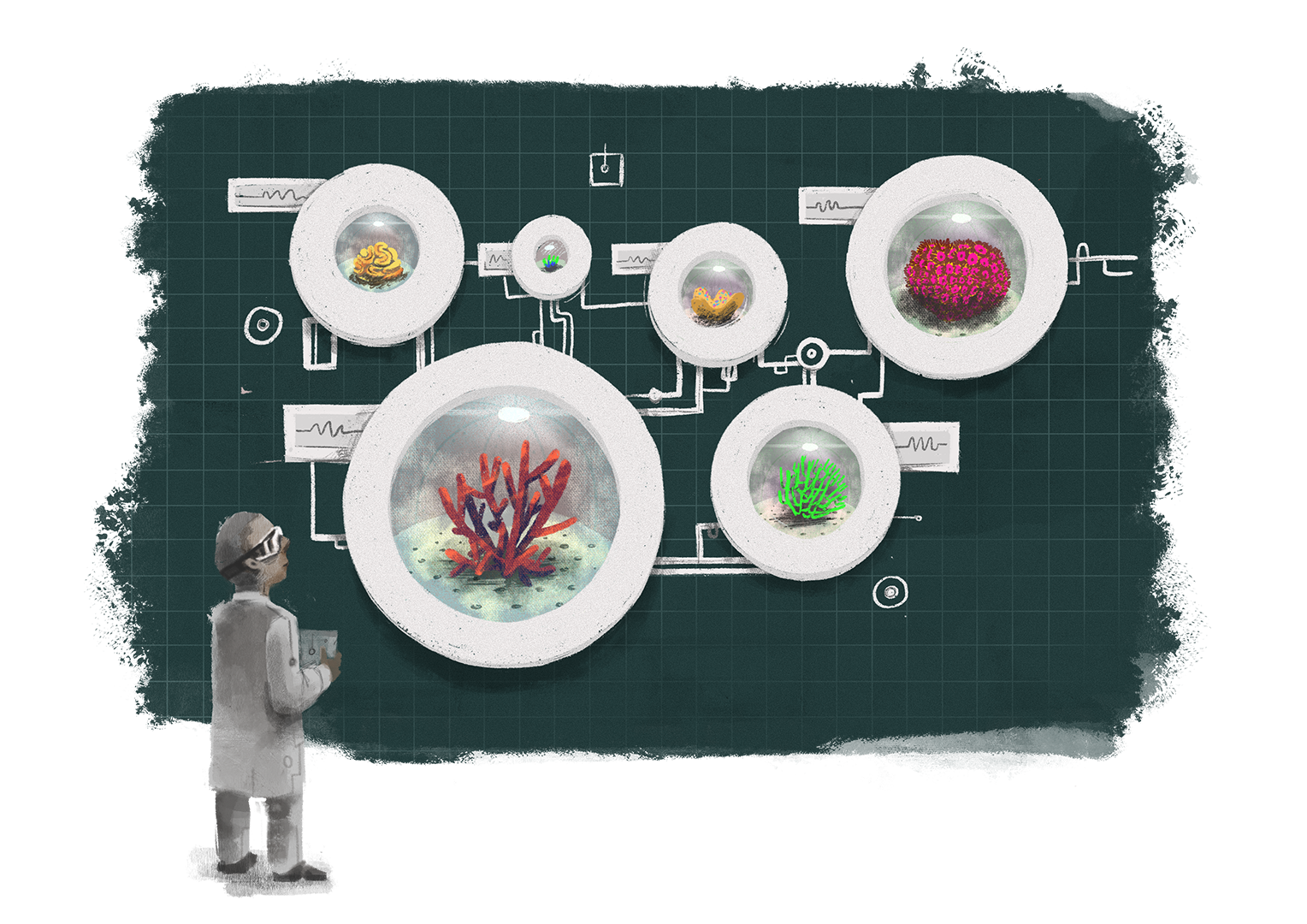

Corals were capable of building reefs for 500 million years, until the temperature of the sea began to soar. When the myth of rising temperatures soon turned real, scientists began to realize that it was too late to save the world’s biggest reef. The Great Barrier, had been reduced to small fragmented mounds, devoid of life, and far from the thriving ecosystem it had once been. Last November the sea surface temperatures in Australia averaged above 34 degree Celsius, making it almost impossible for any rehabilitation effort to succeed. The only living representatives of the once abundant corals were now maintained in aquariums under thermostatic conditions at Reef Headquarter, Townsville – one of the largest reef aquariums in the world.

Coming back to how the last of the reef building corals were born in the wild, it was a surprise in every way. I never imagined having the privilege of observing the phenomenon first-hand. It could have easily gone unnoticed. It had been over 14 years since the world had given up on searching for corals in the wild. I was once a researcher interested in coral reproductive biology, but massive bleaching events wiped the reefs clean from the world’s oceans. Hence, I had moved on to study algal blooms and ocean warming. The probability of being in the right place at the right time, to observe and document the birth of wild corals, still makes me wonder.

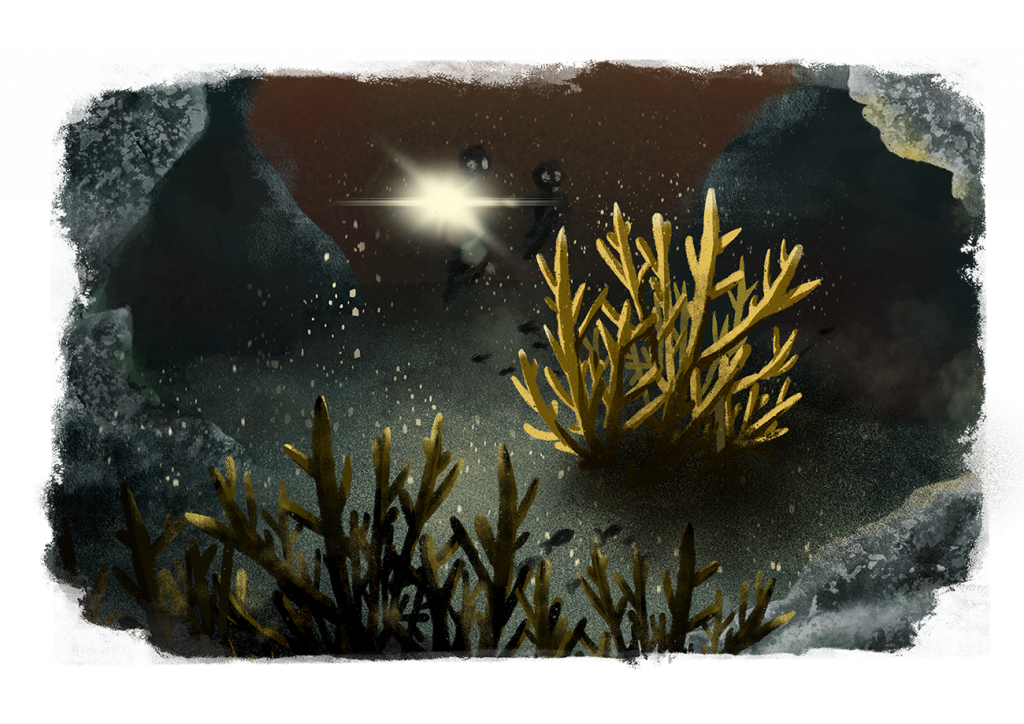

The last corals were not the massive gigantic boulder corals that guarded barrier reefs. In fact, they were nowhere near the barrier reefs. In an atoll far away in the Arabian sea, in the deepest depths of a lagoon, stood the last stand of wild coral – the delicate staghorn coral.

Maybe it was because of the monsoons (characteristic of the region) that had given respite from the scorching summers, which had bleached all the other reefs dead, or maybe it was the shelter of the lagoon, which allowed that stand to survive. Whatever the reason, it was the last ideal place in the ocean for a coral species. Leading research on coral had centred on the reefs of Australia, America and other regions where environmental science and climate change research was well-funded, but many countries with more pressing matters to attend to, had forgotten to record the parameters of many of these important pockets of resilience.

What I saw felt like a dream! I’d anchored my boat in the back reef of the atoll and was sampling the water with my husband, when slowly, tiny pink eggs broke the surface to form a reasonably clear pink slick. I initially refuted the idea, but the pinkness of the slick looked undeniably like that of coral eggs.

We dived down to a surprising depth of 20 m. This was unnaturally deep for a lagoon. There, in the shadow of a ridge made up of towering dead boulder coral, existed a silent garden, fish flitting in and out of the delicate branches. Almost uniformly sized bushes stood still in the dull moonlight. As I switched on my torch, yellow eggs like spangles floated towards the surface, leaving the blue-tipped branches of their parents – the last surviving corals in the wild. We recorded the event and hurriedly returned to collect the spawn slick, which we cultured into planula larvae. We shipped them to every major coral aquarium that we possibly could. The ‘last stand’ was all over the news.

I had no idea that after all that hype, it would be the last time we would see the stand. The next monsoon, a storm collapsed a section of the already dilapidating reef. This might have made the staghorn coral vulnerable to the temperatures of the open sea. We were too late to react. The last stand had died.

Thanks to overwhelming support, we have currently patched up and reinforced the collapsed sections of the reef with scrap metal from a decommissioned merchant ship. Debris and rock now hold the scaffolding firmly intact, thanks to a team of architects and engineers. Marine life around has gradually returned. Two aquaria have been generous enough to contribute live coral fragments of the same species that we lost. We were also able to transplant fragments from adult coral, grown from the spawn we collected years ago at the same location. However, these cultivated corals would not stand a chance without the protection of the reinforced reef.

The last wild stand of coral is gone, and no reports of coral in the wild have resurfaced to date. Our only hope lies in genetically modified, temperature resistant corals. However, with sea temperatures now rising to irreconcilable levels, is it too late not just for sensitive corals, but for all marine life?