“Falcon hunters become fervent preservationists” declared the New York Times in 2015. Just three years earlier, reports of thousands of Amur falcons being hunted in northeastern India shook environmentalists across the world. Today, the Amur falcon story is a well-known example of conservation delivering change. The rapid shift of the local community from hunters to protectors has been widely celebrated. But how was this change negotiated? How was such urgent and long-term change achieved?

The Amur falcon (Falco amurensis) is known for its journey from breeding grounds in northeastern China, Mongolia and eastern Russia (Amurland) to wintering grounds in Africa. During their migration, the birds stop in northeastern India and Myanmar and then the Indian subcontinent, before flying nonstop over 4000 km across the Arabian Sea to Africa—the longest continuous ocean crossing among birds of prey. A significant stopover site in northeastern India is the Doyang reservoir in the state of Nagaland. Amidst hills covered in swidden agriculture, millions of falcons come together and feed on insects over the large artificial reservoir.

This stopover site became famous in November 2012 when a group of conservationists discovered widespread hunting of the migrating falcons. The environmental portal Conservation India launched a media campaign against falcon hunting at the Doyang reservoir. Activists estimated that 120,000 to 140,000 birds were caught in 10 days, about 10% of the global population of adult birds. The media campaign and associated video titled ‘The Amur Falcon Massacre’ drew national and global criticism. India is a signatory to the Convention on Migratory Species; the government was obliged to protect the species.

Following the campaign, the Nagaland state government warned that they would stop funding development projects unless villagers stopped hunting falcons. Most hunters were said to be from the village of Pangti, so it was closely monitored. The Pangti Village Council—the apex governing body in the village—gave in to the pressure. Village leaders banned falcon hunting two months before the 2013 falcon migration season. The hunting and sale of falcons had been highly profitable because hunters would earn up to 10 times their monthly incomes in a single season.

Unsurprisingly, the ban on trapping and hunting falcons was deeply unpopular. Yet, the hunting ban has since been widely praised.

What can the Amur falcon story teach us?

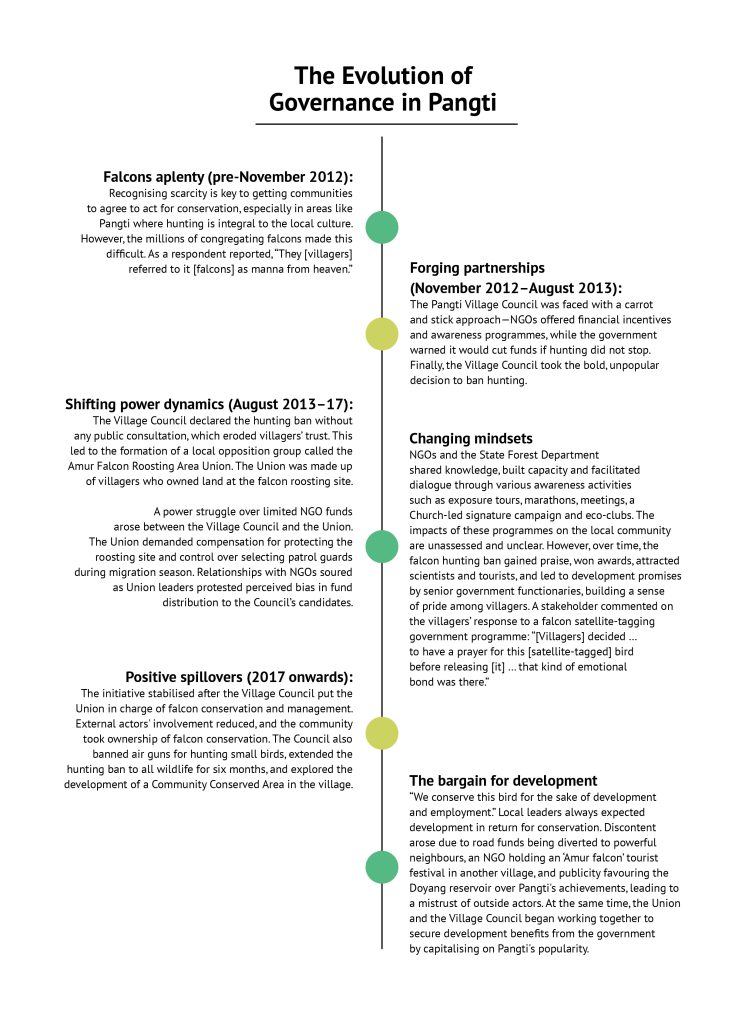

The Pangti case study raises questions about whether and how a conservation initiative starts can shape future outcomes. At Pangti, Amur falcon conservation began with the government forcing villagers to stop hunting. Over time, villagers took over conservation efforts. How did Pangti shift towards community-led conservation? What changes can empower community leaders to protect biodiversity?

Environmental groups often use emotional wildlife imagery in media campaigns to pressure governments into action. Like in Pangti, these campaigns can lead to quick law enforcement. But they may also isolate and vilify local people, and create enmity within stakeholders. It can be challenging to meaningfully engage with the local community after such campaigns. Even harder is helping people feel pride and ownership towards biodiversity. To achieve such change, conservationists need to identify opportunities and gaps in local governance practices that can support environment-friendly rules.

Governance transitions for sustainability have been explored across various fields. So far, science has focused on efforts started and managed by local people or those started by governments. What makes Pangti unique is that conservation rapidly evolved from a government-pressured ban to a community based conservation programme. Thus, Pangti can offer a unique perspective on how conservation can shift towards bottom-up community-led models.

We recently published a paper that studies how governance evolved at Pangti since the first reports of falcon hunting in the journal Conservation Science and Practice. We interviewed 17 key stakeholders who shaped falcon conservation in Pangti village from 2012–19. These stakeholders included local and national NGO representatives, village leaders and government officers. The study provides an in-depth perspective into how the decisions that shaped one of the most wellknown conservation programmes in the world were made. A complete picture of conservation governance at Pangti can emerge by examining changes across time and complexity.

Lessons for Conservation Practitioners

Pangti has come a long way since the first reports of falcon hunting, but challenges still exist. Villagers have often felt disappointed because their hopes for development remain unfulfilled. Road infrastructure remains poor, limiting tourism. Equity issues may persist if those who lost seasonal incomes after the ban cannot benefit from tourism. The lack of alternative livelihoods and untapped tourism potential in a region with high deforestation and water scarcity are a missed opportunity for conservation. However, the falcons offer a promising chance to turn things around—not only in Pangti, but also at roosting sites across Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram.

The case study of Pangti makes it clear that community support can be built even when conservation begins with criticism and threats. But this transition needs an open dialogue with local stakeholders. Outside actors, such NGOs and government officers, must respect the legitimacy of existing local institutions and the rights of local actors. While negotiating for conservation, it is important to be fair and transparent.

Further, rapid shifts towards conservation will often create losers and winners. Hence, managers should identify people who were negatively impacted by conservation. Minimising economic losses is critical to win broad popular support. Recognise local demands (e.g. development) that may be at odds with conservation, and design approaches to meet these demands in a clear, equitable manner. Equally important is fostering leaders who can cut through the red tape, share information and build institutional memory for future generations.

Further Reading

Herrfahrdt-Pähle, E., M. Schlüter, P. Olsson, C. Folke, S.Gelcich and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2020. Sustainability transformations: Socio-political shocks as opportunities for governance transitions. Global Environmental Change 63: 102097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102097.

Kudalkar, S. and D. Veríssimo. 2024. From media campaign to local governance transition: Lessons for community-based conservation from an Amur falcon hunting ban in Nagaland, India. Conservation Science and Practice 6(8): e13191. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.13191.

Salerno, J., C. Romulo, K. A. Galvin, J. Brooks, P. Mupeta-Muyamwa and L. Glew. 2021. Adaptation and evolution of institutions and governance in communitybased conservation. Conservation Science and Practice 3(1): e355. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.355.