Feature image: A sambar deer peers through a dense Lantana thicket in Kanha. (Photo credit: Neha Awasthi)

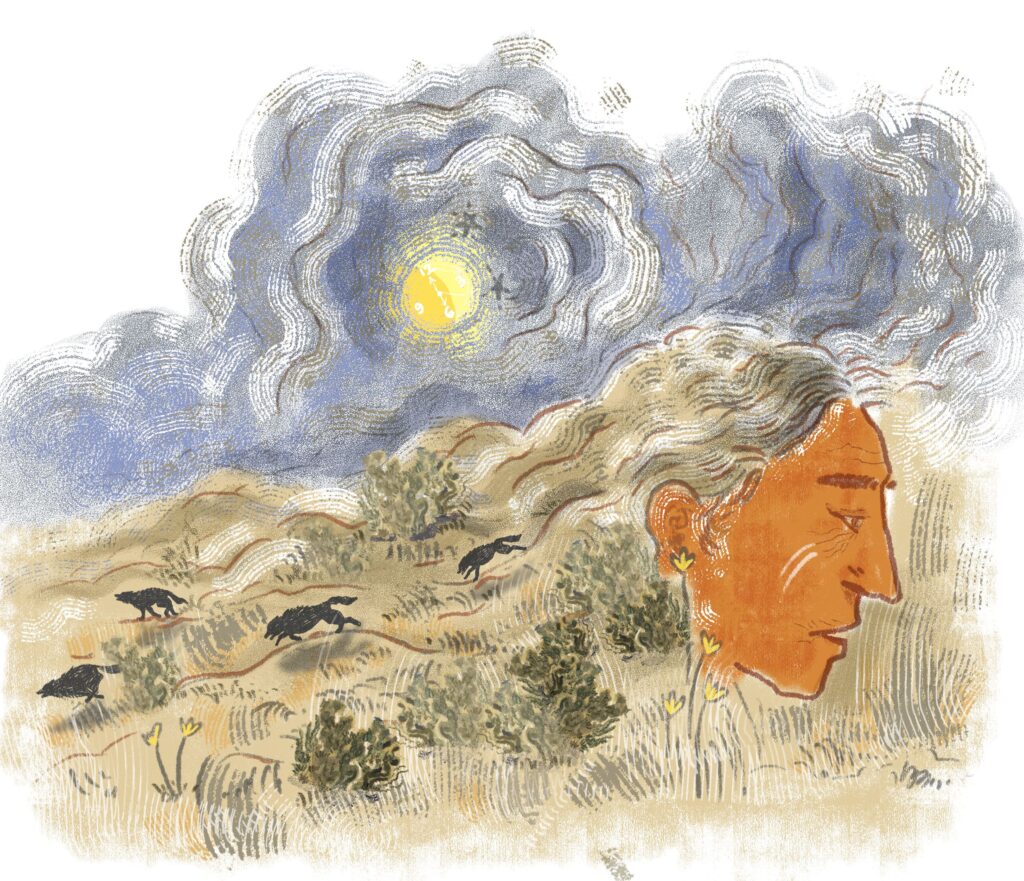

It was early morning in the Kanha Tiger Reserve in Central India. The quiet made my own footsteps sound too loud. There was a slight chill in the air, so I kept my hands in my pockets as I walked through the sal trees to the same spot where I always sat—within a small opening behind a bamboo clump. Here, I knew that I could keep out of sight. With binoculars around my neck and a notebook tucked under my arm, I waited. Months in the field had taught me not to chase, but to simply sit and wait for the deer to come to me.

A sambar stag emerged from the treeline. He stood there for a brief second, backlit by the morning light. His antlers caught the sun and made him look almost golden around the edges. He walked in slow, deliberate steps towards the undergrowth looking for breakfast. I thought he had started eating something familiar. Probably one of the native shrubs or a patch of grass. But I was mistaken. His choice of food caught me completely off guard. He bent his head and started feeding on Lantana camara, a thorny, toxic invasive plant, native to the American tropics and known more for its aggressive spread in non-native regions than its nutritional value. The stag didn’t take a bite and move on. He continued feeding on the woody shrub, leaf after leaf, as though it was a regular part of his diet. The scene lasted only a few minutes, but it stayed on my mind for months, forever changing the way I view the forest.

Tracking diets

I had come to Kanha to carry out my PhD study on the foraging behaviour of sambar (Rusa unicolor)—a large deer species native to the Indian subcontinent, South China, and Southeast Asia. I applied a standard bite count method, watching them eat through various seasons and across different forest types, such as sal, bamboo-dominated, and mixed growth. A fieldwork session meant carefully recording every plant they consumed (including how many mouthfuls of each) during fixed observation periods, along with details such as the habitat type, time of day, and whether the deer were alone or in a group. It required patience. Some days, I barely caught sight of a deer. On others, I’d be lucky enough to observe undisturbed feeding for more than an hour.

Before long, an unusual pattern started to emerge. Lantana kept appearing in my notes as the species’ choice of food, even when plenty of native plants were available. After a few weeks, the pattern was hard to ignore. In several patches, Lantana made up more than 15 percent of the sambar diet. In terms of dry weight, the invasive plant’s contribution was even higher. What struck me most was that even in areas where native shrubs were present, the deer seemed to prefer Lantana. They were actively choosing it. But why were the deer consuming so much of a plant known to be chemically toxic?

I began to ask myself questions I hadn’t expected. Was this a matter of limited choice? In sites heavily invaded by Lantana, were the deer simply making do? Were they still feeding on this weed in healthier forest patches? Were the deer immune to the adverse effects of Lantana consumption, such as liver damage, recorded in studies on livestock?

Toxic properties

Lantana camara is not native to Indian forests. Over 200 years ago, the species was brought here from Central or South America as an ornamental plant. It grows thick and fast, thereby outcompeting native plants and making it harder for forests to recover from disturbance. Today, it has overwhelmed millions of hectares across the country. The result is that native ruminants, such as sambar or spotted deer, are encountering this plant for the first time.

Forests rarely shout. Most of the time, they whisper. And you only notice if you are quiet—a small shift in diet, a subtle change in behaviour, a pattern that repeats itself until it can no longer be ignored. Watching a sambar feed on Lantana was not dramatic. It was quiet, almost easy to miss. Yet, the moment stayed with me. It got me thinking about how animals cope when things around them start to change—when forests lose their biodiversity, when good forage becomes harder to find, they don’t always get to choose. They adapt. Sometimes that adaptability looks like compromise. Other times, it might look like a risk. Maybe the sambar did not prefer Lantana. Maybe it just didn’t have any better options.

To imagine that Lantana could become a key food source is surprising—it contains a chemical known as lantadene, which is toxic to animals. This has been documented by veterinarians for years, with consumption of this species found to cause photosensitivity and liver damage in cattle, proving fatal in some cases. So seeing a wild herbivore feed extensively on the plant was both puzzling and worrying. Was it a sign of desperation? An adaptation? A mistake? There were no easy answers. And that, perhaps, is what made this finding so important to me.

Ecological implications

These deer are not silent grazers in the forest. They are an essential part of the ecosystem. As large-bodied herbivores, their foraging shapes plant communities. They influence seed dispersal and, perhaps most importantly, they are a primary prey species for big cats such as tigers and leopards. If their health starts to suffer, the effects ripple throughout the food chain as well as the ecosystem.

A steady diet of Lantana, low in nutrients and known to be toxic, could lead to weakened body conditions, reduced reproduction rates, higher chances of disease or being easily killed by predators. Thus the question of why deer are feeding on Lantana is not just about the deer, but also about the predators that rely on them and the ecological balance of the entire forest.

When we talk about invasive plants, we usually think about overcrowding, toxicity, and pushing out other plants. But the full story may only become visible by considering the behaviour of the animals that live among them. What are wild herbivores eating and why?

Some of my strongest field memories are not dramatic sightings, but quiet moments: a line of sambar easing through a Lantana thicket, stopping and starting as they feed, or a hind with her fawn holding still in the half-light, taking careful bites from the edge of a bush. These memories are marked by hours spent with a notebook, recording each bite, then staring at the page and wondering what the data mean.

Looking back, those days taught me more than I expected. I went to Kanha to study foraging behaviour, but came away thinking about the silent negotiations between species every day. I found no clear evidence that sambar are immune to the toxic effects of Lantana camara. Whether their continued consumption reflects physiological tolerance or simple persistence under constrained forage conditions remains an open question. What the sambar eat, where they step, what they pass by—these are not just behaviours, but signals.

Over time, I began noticing other small shifts: denser Lantana thickets replacing diverse understory plants, deer spending more time along forest edges, and longer feeding bouts with fewer plant species. The story of a forest is not always about what is lost outright. Often it is about what changes slowly, almost unnoticed. Sometimes it begins with a deer pulling leaves from a thorny Lantana bush.

Further Reading:

Rastogi, R., Q. Qureshi, A. Shrivastava and Y. V. Jhala. 2023. Multiple invasions exert combined magnified effects on native plants, soil nutrients and alters the plant-herbivore interaction in dry tropical forest. Forest Ecology and Management 531: 120781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120781.

Roy, H. E., A. Pauchard, P. J. Stoett, T. R. Truong, L. A. Meyerson, S. Bacher, B. S. Galil et al. 2024 Curbing the major and growing threats from invasive alien species is urgent and achievable. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8: 1216–1223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02412-w.